In the early twentieth century, newsboys were a characteristic of the urban landscape, a ubiquitous presence on big city street corners across America. Boys and girls as young as five or six peddled penny and two-penny papers in the wee morning hours, during the school day, and long, long, long after dark. On muggy and sunny summer days and on blustery winter nights, children sold the news and collected their pennies. In 1900, there were ten major, general-circulation newspapers in Chicago and dozens more specialty publications, as well; and at least 4,000 newsboys and newgirls sold them from established newsstands, from pull carts advertised with newspaper mastheads, from makeshift box displays, and from right out from under their own little arms. The exuberant voice of the newspaper crier, which cut above the chaotic din of the bustling Chicago streets, was more often than not the voice of a child.

In the early twentieth century, newsboys were a characteristic of the urban landscape, a ubiquitous presence on big city street corners across America. Boys and girls as young as five or six peddled penny and two-penny papers in the wee morning hours, during the school day, and long, long, long after dark. On muggy and sunny summer days and on blustery winter nights, children sold the news and collected their pennies. In 1900, there were ten major, general-circulation newspapers in Chicago and dozens more specialty publications, as well; and at least 4,000 newsboys and newgirls sold them from established newsstands, from pull carts advertised with newspaper mastheads, from makeshift box displays, and from right out from under their own little arms. The exuberant voice of the newspaper crier, which cut above the chaotic din of the bustling Chicago streets, was more often than not the voice of a child.

And where there was the voice of a child on the streets of Chicago, there was, of course, Jane Addams. In a number of speeches in the early 1900s, Addams argued that “something should be done to take the babies from the streets.” Through her work at Hull-House, Addams witnessed firsthand the dangers faced by children who earned a living on the urban streets. Popular culture has romanticized the newsboy as a “saucy, chattering” chap, whose smudged, little face and crooked Gatsby-hat belied street smarts and worldliness that made him wise beyond his years. Yet Addams would never have succumbed to such romance, for her experiences had shown her otherwise. So while Chicago’s newsboys raised their voices to sell Chicagoans the news, Jane Addams raised her voice to protect them.

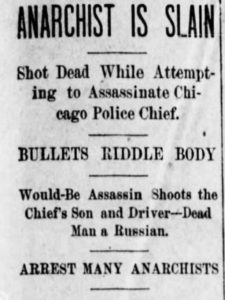

Many programs at Hull-House kept children off the streets, maybe even keeping some from resorting to the sale of the evening news. Addams spent a lifetime lobbying for child labor laws, and her hard-hitting articles and widely attended speeches raised public awareness about the difficulties of life for poor children, particularly those of Chicago’s immigrant families. But as was the way of the world in the Progressive Era, many children in the inner city had few choices; and for some, the freedom of movement and money in pockets made selling the news quite an alluring prospect. There were a few newsboys who made $3-5 dollars a day. One small Italian boy named Antonio, who operated two stands on the corner of Clark and Monroe streets, sold 1,000 newspapers a day. The thirteen-year-old Antonio had inherited the prime location from his father, and he benefited from a corner monopoly at a very lucrative location. Antonio was one of the lucky ones, however. Most newsboys were fortunate to take in a fraction of Antonio’s income, as typical pay was just 50 cents per 100 penny papers sold each day; and most did not have the luxury to stand still in one spot and sell such a large quantity of papers. Instead, they lugged heavy, wheeled carts, toted bulky satchels, or secured their product under their arms, as they searched the streets for customers. And it was those roaming newsboys who were, of course, most vulnerable to the dangers and temptations of the city.

Children selling papers at rush hour, at dark, in terrible weather, and without protective supervision faced many perils. In June 1903, Cornelius Scanlan, a twelve-year-old newsboy was selling papers to street car travelers on 47th street when he was hit and killed by a northbound train. Many newsboys were orphans or from poor families and were inadequately attired for Midwestern rains and for Lake Michigan cold. One newsboy named Peter was found sleeping in News Alley at 2 a.m. on one of the coldest days of the winter. He claimed to be an orphan who came to Chicago from Milwaukee. Weather was a constant problem for those who worked and lived out of doors. Newsboys were also frequently the victims of crime. William Cullen was a blind newsboy who was “a familiar figure” at Blue Island Avenue and Twelfth Street. He sold newspapers from a small wagon and with the protection of a dog, but one night as he slept two men stole his newspaper stand, jeopardizing his means of subsistence.

Particularly troubling was the potential for sexual assault. The Chicago police collected evidence on one adult news dealer who had a prosperous corner on Halsted Street. He made eight boys who worked for him come to his room to receive their pay “and there committed violence” on each, most under the age of 14. One-third of the newsboys sent to one reform school in Chicago had venereal disease, an unfortunate reality for many kids who risked life and health on the streets. Of course, even those who were not abused suffered lung ailments and other sicknesses that went untreated; and if they became too unwell to sell papers, they lost income, as well. Sadly, too, adults who should have protected them were often the perpetrators of mistreatment. Many parents, some desperate themselves, pressed these children into the newsboy “economy.” Police officers were sometimes guilty of harassment, as some in Chicago took payoffs from newspaper companies to guarantee particularly lucrative corners, muscling away newsboys who “trespassed” upon those monopolies, and even arresting others for loitering.

In 1902, a group of some 200 newsboys organized the Chicago Newsboys’ Protective Association. This union tried to mediate the conditions of newsboy employment with newspaper publishers, to lobby for better conditions, and to help members who were sick or injured. Strides were minimal, and the streets were no less dangerous. As well, newspapers in this era had multiple editions, and papers were published at morning, at noon, and at night. As such, days for newsboys were often long; and truancy from school was a common problem. Working on  the streets also exposed newsboys to the temptations of gambling, smoking, and other vices that resulted from a vagrant lifestyle. Some of these kids were runaways. Edward Fink, a twelve-year-old from South Bend, Indiana, took $30 from his mother and traveled to Chicago on a freight train. He was selling papers on the streets of Chicago and living with other newsboys when he was arrested and returned to his parents. Another boy, a sixteen-year-old from Texas moved to Chicago to work as a newsboy because black newsboys were not allowed in his town. But when he arrived in South Chicago, police arrested him for vagrancy.

the streets also exposed newsboys to the temptations of gambling, smoking, and other vices that resulted from a vagrant lifestyle. Some of these kids were runaways. Edward Fink, a twelve-year-old from South Bend, Indiana, took $30 from his mother and traveled to Chicago on a freight train. He was selling papers on the streets of Chicago and living with other newsboys when he was arrested and returned to his parents. Another boy, a sixteen-year-old from Texas moved to Chicago to work as a newsboy because black newsboys were not allowed in his town. But when he arrived in South Chicago, police arrested him for vagrancy.

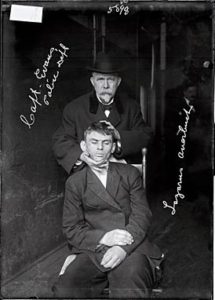

In 1903, Jane Addams was part of a two-day investigation into the lives of newsboys in Chicago. Commissioned at the behest of the Federation of Chicago Settlements, a committee of twenty investigators hit the streets to interview 1,000 newsboys (including 20 newsgirls) in Chicago’s “Loop.” They reported that “while favorable to the legitimate features of the newspaper industry” their investigation confirmed their “impression that Chicago needs a city ordinance which would obviate many of the abuses now apparent in the news trade.” The committee printed a 28-page, illustrated pamphlet, which outlined the work and social conditions of the children who sold newspapers and offered proposals for child labor laws to protect them. The investigation in Chicago reported that the newsboys they interviewed had ranged in age from 5-22 and that 127 of them (12%) were under the age of 10. Among the number, Italian, German, Irish, and Jewish immigrants were numerous. The investigators turned up one five-year-old child and five other kids who were just six. The report noted that “the small boy, under ten years of age, is on the ragged edge of the newspaper business.” No doubt, younger newsboys faced the most hardships and dangers, too.

The pamphlet garnered some attention, but six years later Addams was frustrated. In a speech in March 1909 about children and street  trading, she complained that newsboys had fallen in the category of “merchant” and were not subject to child labor regulations. Addams was annoyed that even as Illinois had enacted a child labor law, which should have limited the working hours of all children and protected them from harsh labor conditions, it did not apply to Chicago’s newsboys. “So far, we have been unable to secure any legislative action on the subject,” she lamented. “It is a very disgraceful situation, I think, for Chicago to be placed in while the Illinois child labor law is so good. The City of Chicago is a little careless, if not recreant, towards the children who are not reached by the operation of the state law.” And so, Jane Addams’ battle for the safety and wellbeing of all children would continue.

trading, she complained that newsboys had fallen in the category of “merchant” and were not subject to child labor regulations. Addams was annoyed that even as Illinois had enacted a child labor law, which should have limited the working hours of all children and protected them from harsh labor conditions, it did not apply to Chicago’s newsboys. “So far, we have been unable to secure any legislative action on the subject,” she lamented. “It is a very disgraceful situation, I think, for Chicago to be placed in while the Illinois child labor law is so good. The City of Chicago is a little careless, if not recreant, towards the children who are not reached by the operation of the state law.” And so, Jane Addams’ battle for the safety and wellbeing of all children would continue.

The remarkable, illustrated pamphlet that Jane Addams and her group published is now a part of the Jane Addams Digital Edition, where you can read the document in its entirety. You will also, no doubt, enjoy the poignant photos of real newsboys and newsgirls who worked on the gritty streets of early twentieth-century Chicago.

By Stacy Linn, Assistant Editor

Sources: Jane Addams, “Address to the Merchants Club, March 8, 1902,” Jane Addams Digital Edition; Jane Addams and Federation of Chicago Settlements, Newsboy Conditions in Chicago (1903),” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed March 31, 2017; Chicago Daily Tribune, 7 May 1903, 3:1; 24 June 1903, 1:6; 9 October 1903, 4:3; The Inter Ocean (Chicago, IL); 5 August 1903, 9:5; 13 September 1903, 25:1-7; Aaron Brenner, Benjamin Day, and Immanuel Ness, eds., The Encyclopedia Strikes in American History (New York: Routledge, 2015), 614; “Chicago Newspapers,” https://chicagology.com/newspapers/; Myron E. Adams, “Children in American Street Trades,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 25 (1905): 23-44. The photos featured here are included in Newsboy Conditions in Chicago.

A scholarly editor and historian, Stacy Lynn formerly edited the papers of Abraham Lincoln and currently is an editor at the Jane Addams Papers Project.

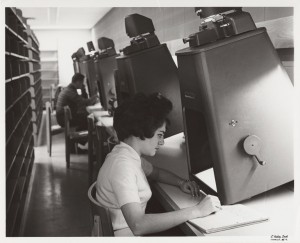

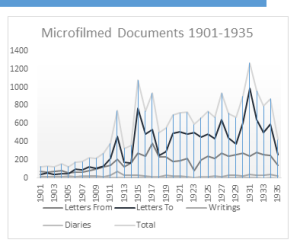

Between 1976 and 1983 the original staff of the Jane Addams Papers Project, led by Mary Lynn Bryan, undertook a massive search for Addams documents, searching thousands of archival collections and locating documents in 574 of them. These documents, microfilmed in 1996, will serve as the base of the new Jane Addams Digital Edition. We estimate that they found almost 20,000 letters from the period between 1901 and 1935. They also found evidence that not everything had been preserved. Some documents were lost, but others were deliberately destroyed.

Between 1976 and 1983 the original staff of the Jane Addams Papers Project, led by Mary Lynn Bryan, undertook a massive search for Addams documents, searching thousands of archival collections and locating documents in 574 of them. These documents, microfilmed in 1996, will serve as the base of the new Jane Addams Digital Edition. We estimate that they found almost 20,000 letters from the period between 1901 and 1935. They also found evidence that not everything had been preserved. Some documents were lost, but others were deliberately destroyed.