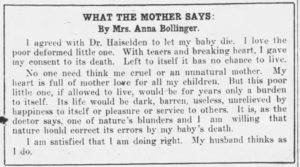

A little over 100 years ago, the case of an infant allowed to die in a Chicago hospital captured the nation’s attention. Born on November 12, 1915, “Baby Bollinger” died five days later on November 17, after physician Harry Haiselden refused to operate to save his life. Haiselden made his decision because the child was born with deformities and he believed the the boy was was mentally and morally defective. He convinced the child’s mother, who said “the doctor told me it would be, perhaps, an imbecile, a criminal. Left to itself it has no chance to live. I consented to let nature take its course.” (Boston Globe, Nov. 17, 1915, p. 1.) Haiselden’s controversial decision led to a heated debate in newspapers across the country.

The baby, John Bollinger, was the fourth child of Anna and Allen Bollinger of Chicago, was born with noticeable disabilities, such as a missing ear and a defect in sk

in development that made it appear that the baby had no neck. Operating on the baby might have saved his life, but Haiselden and other doctors were concerned that as a “defective” the life ahead for the family would be challenging, and that the child would be a burden to society.

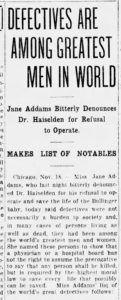

When news of Haiselden’s decision became public, people began calling and begging the doctor and hospital to reconsider the decision. There were threats to kidnap the baby and take him to another hospital. Leaders weighed in on the issue, including Jane Addams. As a firm believer in equal rights for all, Addams was appalled by Haiselden’s decision. “A physician or hospital board has not the right to assume the prerogative to say that any person shall be killed, but is required by the highest moral law to save every life that possibly can be saved.” (Richmond Item. November 18, 1915.)

Addams offered a list of famous, notable, and historical people who suffered from disabilities (see full article). Helen Keller, John Milton, Lord Byron, and Robert Louis Stevenson were a few named on Addams’ list. Each had made great contributions to society; notwithstanding their disabilities.

Another critic was Dr. James Walsh, who wrote:

The physician has assumed the exercise of a power that is not his. Doctors have the care of life, not death. Physicians are educated to care for the health of their patients, but so far at least as I know we have no courses in our medical colleges as yet which teach how to judge when a patient’s life may be of no service to the community so as to let him or her die properly. Some of us physicians may thank God that we are not yet the licensed executioners of the unfit for the community, and some of us know how fallacious our judgments are even with regard to the few things we know (www.psychologytoday.com)

Haiselden’s critics made moral arguments, claiming that every person has a right to live and doctors must not play God and determine who lives or who dies, but should respect the lives of all patients and give them the best care and treatment. Many believed that the hospital had committed murder and demanded answers.

Some supported Haiselden’s decision, explaining that it was “a mercy to let babies with disabilities die rather than to allow them to experience a lifetime of ‘pain, shame, humiliation, and distress.'” Dr. William Rausch, Jr. from Albany, New York, was one supporter. He wrote that it was humane to “forget” to cut the cord of newborns with disabilities and let them hemorrhage. Even some parents of children with disabilities wrote in support, saying that death might have been better instead of subjecting their children to abuse in asylums, not knowing where to turn, or worrying about what would happen to their child after its parent’s died.

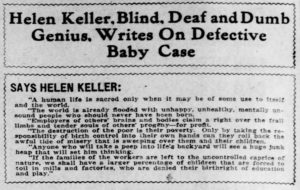

Helen Keller issued a statement that “a human life is sacred only when it may be of some use to itself and the world. The world is already flooded with unhappy, unhealthy, mentally unsound people who should never have been born.” (Pittsburgh Press, November 28, 1915, p. 14.)

An autopsy was performed that vindicated Haiselden. On November 18 the coroner’s physician claimed that though the operation may have saved the child’s life, “the baby, if it had lived, would have been a paralytic and a cripple all its life.” Haiselden testi

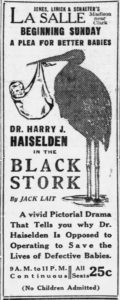

fied before a jury of physicians charged with determining whether he should be prosecuted. He was not charged, though the jury censured him mildly. Haiselden was also tried by the Chicago Medical Society’s Ethics Board, for breaching ethics by publishing a book about the case and talking to newspapers during the events. He claimed that he received no monetary gain from the case, and that the “publicity the case had received had been of great benefit to the cause of eugenics.” In 1916, Haiselden was dropped as a member of the Society, but continued working as a physician on similar cases and speaking out for his point of view. In the same year Haiselden created and starred in a film entitled The Black Stork, which promoted euthanasia and continued commenting on the case and issue itself. The film was ridiculed and heavily criticized. A Billboard review said the film was, “a mere cataloguing of the pitiable mess of human dregs which is left, crawling, crippled and criminal, after the fire has burned out.”

Haiselden did not live to enjoy his fame. He died in 1919 of a cerebral hemmorhage. The mother of the child, Anna Bollinger, died in 1917 after two years of “settled melancholy” over the case.

For more on the case, see Elliot Hosman, The Short Life and Eugenic Death of Baby John Bollinger, Psychology Today, October 12, 2015.

The caption for the first photo of Anna Bollinger with the Doctor, the name is mentioned as Dr Henry Haiselden. Isn’t it Harry Haiselden?