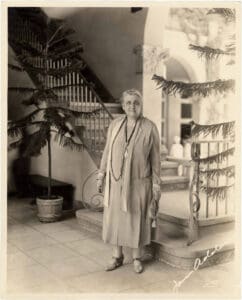

The Selected Papers of Jane Addams: Volume 6, 1914-1935

Edited by Stacy Lynn, with Cathy Moran Hajo

Forthcoming, University of Illinois Press.

Volume 6 focuses on Jane Addams’s growing activism in the peace movement and her advancement to international prominence. With the outbreak of World War I in Europe, Addams joined other women leaders in calling for peace and mediation, forming national and international organizations to lobby belligerent governments and influence American foreign policy. She became president of the Woman’s Peace Party in 1915, and led an American delegation to the International Congress of Women at The Hague in April of 1915, where she was elected president of the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace. In the United States, however, Addams’s message was unpopular and she began receiving negative press, especially as the United States moved closer to entering the conflict. Addams was a vocal opponent of war preparedness, lobbying Congress to prevent an increase of the military budget and meeting with President Wilson to discuss America’s role as a mediator for peace. Once that battle was lost, and the United States entered the war, Addams and other peace activists were faced with a difficult decision–to continue to oppose the war and work against the U.S. government or to fall in line behind the government and support the war effort. Addams chose the former and continued to speak out against war and for peace. She was vocal in her opposition to conscription laws and the 1917 Espionage Act, which criminalized opposition to the government.

Addams was roundly criticized, even by former allies and Hull-House residents, as pro-German, anti-American, or just a foolish woman. As press and public opinion turned against her, she was even accused of treason. This had a serious impact on Hull-House, which lost support and donations during these years. Addams joined others to start the Civil Liberties Bureau (later the ACLU) in 1920 to defend the civil rights of those who disagreed with the government. With the end of hostilities, Addams and other peace activists hoped to influence the terms set for peace. They were critical of the punitive terms negotiated in Paris and worked with the American government, the Red Cross, and Quaker groups on relief efforts for women and children. The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) was founded in 1915, with Addams as president, to bring women together to work for peace, equality, and improved relations between nations.

The years following the war were dark ones for Addams, as America turned away from her ideals of cooperation and progressive social reform. The government cracked down on dissent, deporting and arresting anarchists and communists. Congress rejected the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 in part because it proposed to bind the United States to the League of Nations. The one beacon of hope came with the 1920 passage of the woman suffrage amendment. The volume ends with Addams’s Peace and Bread in Time of War, published in 1922, in which she described peace as more than the absence of war, but as a condition under which people could work together for the betterment of society. In her personal life, Addams lost her beloved sister, Alice, in 1915.

During Addams later years her reputation rebounded even as her health steadily declined. We focus on her continued work for peace, including hosting a meeting of the WILPF in Washington in 1924 that attracted the ire of the War Department. Though she retired from the presidency of the WILPF in 1929, she remained honorary president until her death. Addams continued her work for peace in the United States as well, presenting a peace platform at both Democratic and Republican conventions in 1932. The volume will explore the early effects of the Great Depression on the work of Hull-House and its community, as Addams spoke widely on welfare, relief, and unemployment. And it will touch on the growing menace of Fascism in Germany and the WILPF’s concern over the rise of totalitarian governments, including requests to Addams to join anti-Nazi rallies. Addams continued writing, publishing Second Twenty Years at Hull-House (1930), The Excellent Becomes the Permanent (1932), and My Friend, Julia Lathrop (1935).

Addams’s reputation recovered from the battering it took during World War I only at the very end of her life. She was plagued by accusations from the Daughters of the American Revolution and the American Legion that she was a communist sympathizer. Supporters defended her and eventually turned the tide. She received honors, accolades, and honorary degrees, highlighted by her receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. This cemented her revived public status as she was the first American woman to win the coveted award. At the end of her life, her letters to nephew and biographer James Weber Linn reveal her reflections on her life and its key events.

Addams’s health suffered in 1923 when she had an emergency mastectomy in Japan. She survived heart attacks in 1926 and 1934 and had ovarian cysts removed in 1932. Her circle of close friends shrank as Florence Kelley and Julia Lathrop died. In 1934, she faced the most difficult blow—the death of Mary Rozet Smith. This left her alone for the first time in forty years. A few weeks after presiding over the 20th anniversary celebration of the WILPF, Addams succumbed to colon cancer in May 1935 at the age of 74.