Presidential Address, Association for Documentary Editing, October 16, 2009, Springfield, Ill. (Published in Documentary Editing, Vol. 31, 2010, pp. 92-103.)

Cathy Moran Hajo

How many of you remember when the World Wide Web was new? I remember being thrilled by the things I could do, the information that I could find quickly, and the ability to spread the word about our work. I also remember being unsure how the Web would change the practice of editing. Lately, the design advances and the use of Web technology often described in shorthand as Web 2.0 have made me feel that way again. I am excited about the possibilities, but uncertain about some of the underlying premises of Web 2.0 and what it might mean to the practice of scholarly editing. I am not sure that we have agreed upon the best model for digital editions in the Web 1.0 world, but editors and other scholars are already being pressed to move ahead to the next generation of tools if they want to create fundable and cutting-edge work. How will documentary editing fit into a Web 2.0 world? Will we be able to adapt our practices to the changing technology? Before we go too far along, we need to take the time to stop and think broadly about how we want to interact with the Web, with our documents, and with the public. You will hear more questions than answers here—questions that I hope get you thinking because we need to answer them, not only for ourselves and our projects, but for our profession.

What is Web 2.0?

Before we can figure out how it will impact editing, we need to grasp what Web 2.0 means.2 The term was coined in 2004 as a marketing pitch for a conference about the Web. Tim O’Reilly used it to sell the idea that new Web-based tools had caused a major shift in the way that people used the internet. Initially used to discuss the shift from desktop-based applications to Web-based ones, it has come to mean much more. One easy way of thinking about the difference between the old and the new is that Web 1.0 was about the consumption of both information and products, while Web 2.0 is about participation, the creation of communities, conversations, and information. Web 2.0 has come to stand for broader ideas about democratizing the Web and increasing user participation in Web sites. We all know of some of its more popular applications—Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, YouTube, and Wikipedia, of the ubiquity of blogs and wikis, all lumped under the term social networking. For many, Web 2.0 tools are “game-changers,” that challenge the way we organize, produce, and access information. They have decentralized and democratized access to media: one no longer needs a publisher, a news bureau, or a record deal to get one’s ideas, viewpoints, and creativity out to a large and growing audience. Through the Web we can interact directly with people across the block or across the world, and form vibrant communities around common interests that would have been impossible just ten years ago. But it has its critics, among them Andrew Keen, who blames these tools for a cult of digital narcissism that places undue value on the amateurish opinions that he calls “an endless digital forest of mediocrity.”3 But we need to remember that some of this criticism hides a fear or reluctance to engage with a technology that many find difficult.

As I read about Web 2.0 and its possibilities, I have mixed reactions, ranging from skepticism to amazement. When it works, it harnesses the power of an engaged public to build in-depth knowledge at an incredible rate. When it does not work, it makes me feel as if I am eavesdropping on conversations in a high school bathroom, as masses of poorly spelled, self-absorbed ruminations threaten to overwhelm whatever good might be out there. How can we benefit from the best of the Web 2.0 technologies while avoiding the worst? Should documentary editing be influenced by these new tools and ways of organizing information? What happens to us if we do not get on board? I think that if we do not experiment with the underlying challenges of Web 2.0 tools, we may be left on the sidelines.

About 1.6 billion people use the Web.4 That is what is at stake for editions and for historical and literary documents themselves. With access to numbers that stagger the mind, any of our editions ought to be able to attract a far larger and more varied audience than we can reach with our print editions. If we fail to engage with this throng, will our work end up in a print “ghetto,” as each increasingly Web-savvy generation relies more and more heavily on online content?

Longevity vs. Accessibility

The Web 2.0 world is constructed on our computer displays as we open our personalized pages in browsers. The content of my Facebook page is very different from yours; it changes every day based upon the “friends” that I select, the interests that I acknowledge, and what those friends post on their pages. Facebook, a Web 2.0 technology, does not provide content; instead it provides a platform for its users to interact. Like other Web 2.0 tools, it is ephemeral. It may be popular for a few years but then be eclipsed by something newer, better, or just a bit cooler. So the idea of using a tool like this for our editions makes me uncomfortable. Editors come from a long tradition of preparing resources that will last for generations. We cannot conceive of publishing our documents using anything as short-lived as a blog or as ephemeral as a wiki, because there is no guarantee that these tools will be around in five years, never mind fifty. When we turned to digital publications, we sought to create the digital equivalent of the same lasting quality as our print editions.

From the start, with the formation of the Model Editions Partnership in 1995, editors have been advised to take the route that best preserves our digital editions, even though that road might be hard to travel. At the start it required expensive software to encode and display SGML files, and even with the conversion to XML it demands a familiarity with text encoding that comes naturally to very few editors. The results have been mixed, especially for history-based editions, as the complexity of the work slowed the creation of digital editions. Ten years ago, I thought that by this time there would be far more digital editions than there are. They are hard to secure funding for, difficult to produce, and oftentimes difficult for users to access. But many are well done and are as certain to migrate to the next generation of digital texts as any texts produced today. Most succeed in the effort to capture the detailed attention to texts that we value and promote.

I would not argue that we should not use XML and the Text Encoding Initiative’s descriptive schema for our editions, but I question whether this the only way that we can create digital editions. A case worth looking at is the online diary of seventeenth-century civil servant, Samuel Pepys.5 Using blogging software, the site is at heart a daily dose of Pepys’ life. Instead of publishing the entire diary, as a traditional edition might do, the Pepys site gives us one entry at a time, as if Pepys was blogging about his life. It started on January 1, 2003, with the entry for January 1, 1660. Pepys’ diary entry for October 16, 1666 was posted on October 16, 2009.. Pepys kept his diary until 1669, which means that the site will be posting new entries until 2012. But that is not all the site provides. There are popup annotations of important people, some illustrated with portraits. There are identifications of buildings and organizations mentioned in the diary, all gathered into a searchable encyclopedia. There are also what they call “in-depth articles,” contributed by readers on more complex topics, such as the Great Fire of London. A sidebar provides additional information, providing the weather in central England, and links to Parliamentary journal entries, to letters, and to other primary sources that were created on that day. Samuel Pepys is also the first seventeenth-century tweeter. The editor summarizes each diary entry in the ubiquitous 140 characters and posts them on Twitter. You can follow Pepys on Twitter, receive e-mailed updates as his blogs are posted, or subscribe to an RSS feed to receive daily updates. The site fosters discussion groups, populated by experts and novices, where conversations about Pepys and his times flourish. Users make comments about the diary entries, showing a clear engagement with the texts and the historical period.

Simply put, the site is fun to visit. It offers a richly annotated text, and gives us a daily dose of a life very different from our own. It is easy to use and very accessible to the non-expert. The day-by-day release creates a dramatic tension difficult to reproduce in print when one can just skip ahead to the next page to see what happens. As Pepys recounts the Great Fire of London, his efforts to protect his property, tales of loss and bravery, and rumors of a French plot behind it all, the event becomes quite real and personal, doing what documentary editions do best.6

The Pepys editor, Phil Gylford, is a Web site designer and developer. He is not a member of our Association and has no training as a scholarly editor. What he has done, and done well, is to take a resource well known to scholars, and re-purpose it, drawing attention to it in a way that has attracted a large following, far larger I imagine, than would have attended yet another published edition of the diary. But where did he get the text? Well, we find that Gylford used a published edition, in this case, the 1893 version edited by Henry B. Wheatley. Wheatley’s edition was in the public domain, and Gylford did not even need to transcribe the edition himself—someone had already done so and posted the text on Project Gutenberg.7 I am sure that some of you would ask, “Why did Gylford not use the scholarly edition of the diary edited by Robert Latham and William Matthews?”8 We will return to that later.

Gylford linked a number of annotations to the entries. Those published in the Wheatley edition take the form of popups that you can access by mousing over the text. That is not necessarily Web 2.0. But Gylford also enabled comments on the entries, both to give himself a space to add notes or corrections, and to let his readers comment as well. Called annotations on the site, they include speculation, reactions to the story and scenes described, and research added by readers of varying expertise levels.

So, what can we learn from the Pepys Diary that we could adapt to our editions? It starts with the text. Gylford would not have been able to create his site were it not for the heavy lifting already done by Wheatley. Obviously he chose the Wheatley edition over the more complete Latham and Mathews edition because he did not have to secure copyright or permissions from its editors and publishers. The digitized text was also freely available because it was mounted on Project Gutenberg. Gylford acknowledges that the Latham and Matthews edition is more complete, suggesting that readers wanting more should consult it. Gylford’s site is not the only one on the Web using the same text;9 what sets his apart is his creativity in matching the software tool, the blog in this case, to the source material that made the diary come alive. He was not concerned about making his blog last forever. The Pepys diary has been edited and published many times, and his goal was to make it available. One would think that Latham and Matthews had the same goal, and it is disheartening when we find that the acknowledged best version of the text languishes in footnotes and in a select set of libraries, while an older text, less ably created and lacking in completeness, gets far more use. I do not know if there are any plans to digitize the Latham and Matthews edition, which is still in print, but it would seem that the best solution for all might have been a collaboration between Gylford and the scholarly editing team. While editors are undoubtedly the experts when it comes to creating print editions, we are not always the ones best suited for presenting them on the Web.

There seems to be a growing split in the digital humanities, with one branch preferring the creation of highly complicated digital texts, usually using XML to record the intricate details of the text’s creation and meaning. These texts are usually designed for scholars and advanced students to stand as digital versions of our print editions. The other branch is less interested in preparing such complex documents and more interested in producing digital texts more quickly and encouraging more people to use them. The Center for History and New Media at George Mason University offers an example of this kind of work. They create tools like the Omeka content management system to help organize and publish primary sources as Web-based archives and exhibits without becoming bogged down in detailed XML encoding. Which way should editions go? Both branches have their good points, and while scholarly editors generally favor the first, I think we should try our hand at both, even if that means that some of the digital products we create may be ephemeral. The creation of the digital transcription of an historical document, whether as a Word document, a blog post, an HTML page, an XML encoded text, or a simple ascii file, is the work we are best qualified to do. Making that base text as good as it can be by proofreading it and researching is the work that takes the most skill and time. Once we have that, there is no reason to have to settle on only one form of digital publication. Yes, there might be issues with migrating editions published as a blog or a wiki, but if the content is valuable enough, people will find a way to do it.

The Power of 1.6 Billion People

One point six billion people actively use the World Wide Web around the world, with more logging on each year. As editors, our goal has always been to preserve and disseminate important historical and literary documents, using the most appropriate tools available. For most of our lives, that tool was the book, and in some cases microform. It simply is no longer the case in 2009. We count ourselves fortunate to sell 1,000 copies of one of our volumes, but over 20 million people have seen just one 1987 video clip of pop star Rick Astley singing “Never Gonna Give You Up” on YouTube. If you have not been “Rickrolled,” you do not know nearly enough twelve year olds! If you have seen it, it probably means that you were tricked into clicking a link that you thought was one thing, but was instead a cheesy MTV video.10 Something is wrong here. I am not advocating trying to trick people to view our editions, but do we not need at least to try to get a tiny portion of this audience? They are out there—and they clearly have nothing better to do!

Most of our volumes are bought by research libraries, where serious scholars consult them. We do not know how often they are used and have only anecdotal feedback on how they are used. Did we get reviewed, and if so, was it favorable? What libraries purchased the volume? Do scholars use our books in their footnotes? Who contacts the project’s Web site? While this kind of feedback can help us tweak our editions, it rarely causes us to revise our editorial principles or fine-tune selection policies. It is feedback that is slow in coming, and because of the long lead time for publishing volumes, it is equally slow for changes to appear in print. Unless a second edition is published, we cannot even correct the errors found in our volumes. Don’t get me wrong, I like a hardcover book as well as the next editor. My pride in holding our first volume, never mind the sudden interest and excitement of friends and family, was so much greater than when a carton of microfilm was shipped to our offices. We have emotional attachments to books; we respect them more than articles, Web sites, or sheaves of microfiche. But if we acknowledge that our main purpose is to bring our documents to the greater public, the book can no longer be our pre-eminent form of publication. It is not the means by which we can reach a billion people.

We are in the midst of a transition over the control of media and publication and we do not yet know how things will play out. But can we wait around until things are hashed out, until publishers, especially the university presses that publish our editions, figure out how they want to deal with the Web? Are there other options to traditional scholarly publication? How will editors deal with the push for open access, the Web 2.0 imperative to make all materials free and accessible on the Web? As Robert Darnton wrote this past February, “To digitize collections and sell the product in ways that fail to guarantee wide access would . . . turn the Internet into an instrument for privatizing knowledge that belongs in the public sphere.”11 Yet, what about our publishers? What about royalties for the work that we produce? An esteemed colleague characterized these calls for free access as coming from a “kumbaya generation,” who generally work from secure posts at well-endowed institutions. They rarely address the costs of producing and maintaining these works. Should we give away our editions in order to encourage greater use? Some would argue that we can and should, and I tend to favor that camp. But others argue, equally cogently, that it is not possible to break even doing this.12

It is a dilemma. We want high-quality editions, which require effort and attention, but we also want to reach the broadest audience. That audience is fickle, lazy, and cheap. Materials that are not free or are not digitized are often not used. Materials of lesser quality that are out of copyright are often preferred over higher-quality sources that are not free and easy to use. The online encyclopedia Wikipedia offers a good example of this principle. In its initial form, known as Nupedia, the idea was to create a monitored wiki-based encyclopedia, where scholars and experts would manage various subjects, selecting topics, writing articles, and vetting them before they were posted. Have you ever heard of Nupedia? It didn’t work. Participation was sluggish, and the few pages that were created were not so much better than what was already available. But the creators of Nupedia took a risk with a new version, called Wikipedia, that allowed anyone to post or edit an article, with no gatekeepers or scholarly supervision. They rely on Wikipedia’s users themselves to check, improve, and police the work. Who would have thought this would work? Sometimes trying something—even if you do not know what will happen—can result in unexpected and even runaway success. There is a cadre of people who dedicate huge amounts of time to crafting Wikipedia with no payment or even a byline; people who have become intensely protective of the site and are willing to work hard to keep it going. A far larger group of people—myself included—have contributed a single article, or made a few corrections here and there.13 What makes this kind of participation so powerful is the number of people who access Wikipedia’s pages. When you have so many millions visiting, you only need a tiny percentage to participate in order to secure an army of editors who have built a three-million-page up-to-date encyclopedia in less than nine years.14 Wikipedia is among the top ten Web sites in terms of use, friendly and inviting to its contributors, and a successful example of Web 2.0 technology changing how we gather and report information.

But there is a flip side. People use Wikipedia because it is free and because it is easy, even if they admit that it might contain errors, some honest, others more malicious. Web 2.0 culture has embraced the idea that accessibility is king, that it is more important than accuracy. Listen to Paul Graham, a programmer and essayist:

Experts have given Wikipedia middling reviews, but they miss the critical point: it’s good enough. And it’s free, which means people actually read it. On the Web, articles you have to pay for might as well not exist. Even if you were willing to pay to read them yourself, you can’t link to them. They’re not part of the conversation. 15

The phrase “good enough,” I am sure stiffens your back. It tightens my jaw. Good enough is not what editors do. We will craft new editions of previously edited works, like the Wheatley edition of Pepys, specifically because it was not “good enough.” Whether it has inaccurate transcriptions, incomplete or subjective selection policies, or poor annotation, editors demand quality, not only for the scholars that are their main audiences, but for everyone who reads an historical document. Little errors matter and can build into misinterpretations and greater error. We stand as authorities on our subjects and take very seriously the work that we do. But authority is one thing that the Web 2.0 challenges when it states that “good enough” is good enough.16 We cannot let this notion go unchallenged, but it will take some doing to prove to this generation of Internet users that just because it appears on the Internet seventeen hundred times, does not mean it is correct or, more seriously, that it is not malicious and vicious. This is the risk of keeping quality sources behind subscription-based portals.

If we could build a Web 2.0 edition, with a different relationship to our readers, what might it look like? What could we do with the participation of a hundred thousand people? A traditional Web 1.0 edition might measure every time a page was opened and perhaps include an e-mail address where the reader might send feedback. We could run Google Analytics to get a sense of what pages were opened most and where geographically our users came from. Even those small advances provide us more than we know about the uses of our paper publications. But how would we deal with the “holy grail” of Web 2.0, user-created content? That is something that we have shied away from. Part of this is due to our reluctance to yield our role as experts. Do we want to turn our readers into collaborators? How would we do it? We do not know how it would work, or if it would work, but for a minute let us try not to scoff at the idea that by involving our readers we might actually change the way that we edit documents. I am sure it will be challenging, I will bet it will be nerve-wracking at times. Could it be that we fear learning how much, or how little our readers think about our editions?

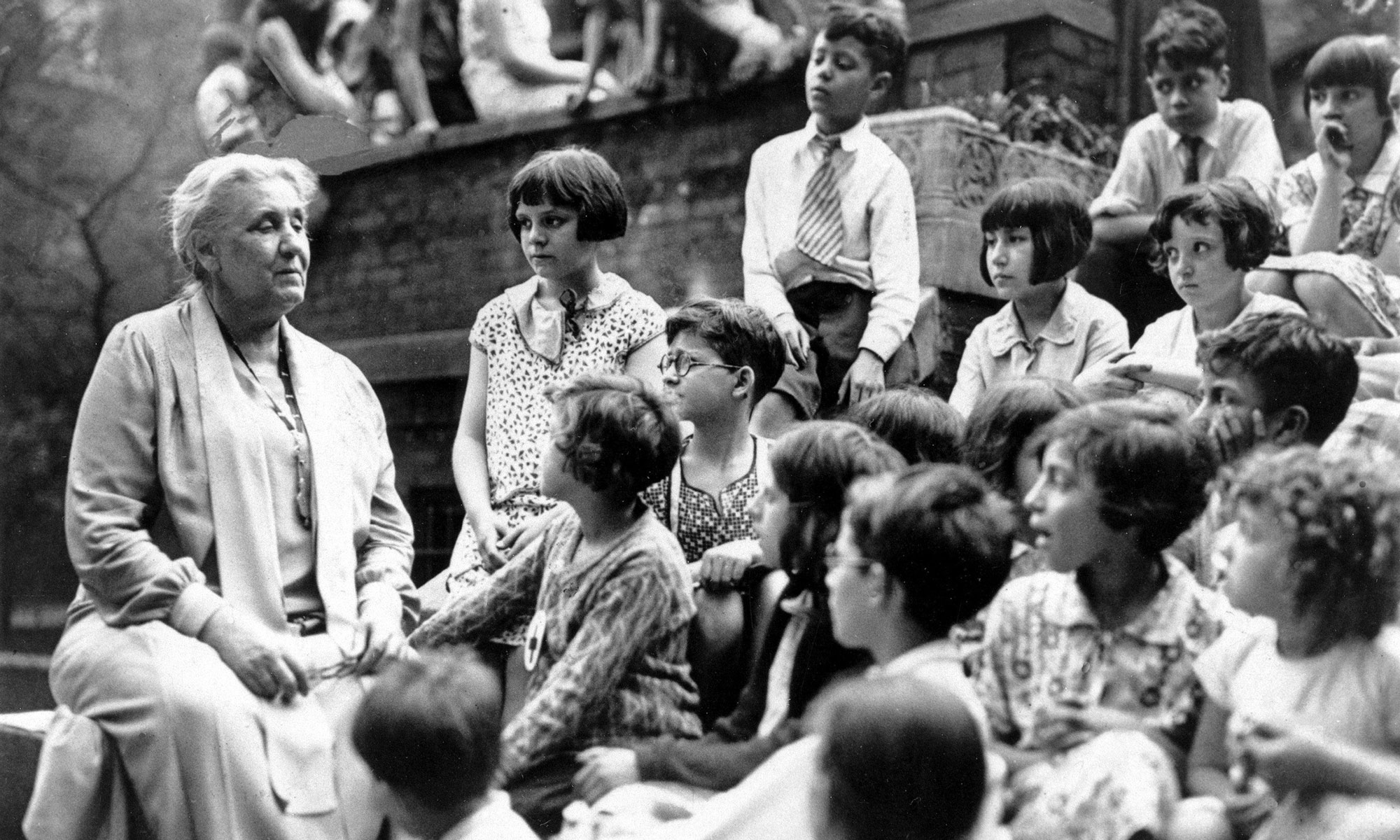

I do not for a moment believe that there is someone in the vast digital wasteland who can read the letters of Thomas Jefferson better than Barbara Oberg and Jeff Looney’s teams; nor do I think that there are armies of armchair historians who can interpret Thomas Edison’s scrawled diagrams better than the Edison Papers staff. I certainly do not believe that document selection or interpretation of Margaret Sanger’s writings on eugenics should be left to activists engaged in the highly charged abortion debate. We have worked hard to gain the expertise and insights needed to edit our documents, trained as scholarly editors, and our immersion into the lives and times of our subjects takes time and talent. But that does not mean that we cannot find roles for our users that could enhance our documents and editions.

The roles that our readers could take would vary from project to project and might include data gathering. We might start by making available some of our research files. If I mounted a version of the chronology database that we use to track Margaret Sanger’s life and allowed people to edit and contribute to it, what do you think would happen? I could envision a hot mess of Sanger haters foaming at the mouth in all the commenting areas, as they do on a number of anti-abortion blogs. But say that we manage, somehow, to keep most of the crazies out and enforce some rudimentary decorum. People are interested in Sanger and her role in the reproductive rights movement and they are also interested in local history. If we could tap into that, perhaps focusing on students of history, women’s history, or public policy, we could encourage readers to scour their local archives and libraries for additional documentation of Sanger’s travels around the country and the world. We would not ask them to build it from scratch—we would provide the dates, as best we have them, and what we know already. For example, based on our chronology database, I know that Sanger was in Illinois at least 53 days between 1916 and 1957. Could we persuade people to survey newspapers, check for photographs and ephemera in local archives, or even identify some of the places where Sanger stayed and spoke and plot them on Google maps? I do not know if they would come, but the interest and enthusiasm that we find among students, interns, and archivists when we tell them about Sanger’s involvement in their own city suggests that some might. It could also expand beyond Sanger. If readers were interested in posting events and timelines of local birth-control activism, the site could become a powerful resource bringing together materials in ways that could help us better understand the birth control movement.

Another way to use social networking is to have users rank or tag the contents of the Web site, and to use the information created to build better searches and to learn about the users. A digital edition might enable a ranking system for documents, much as we might do for Netflix movies or products that we purchased at Amazon.com. As more people provided rankings, software could use them to produce more useful search results. A five-star document would come to the top of the list, while a one star document would remain at the bottom. Users could add subject terms to documents, especially those that have been digitized in image format only, where text searching is not an option. Not only would this kind of social tagging help to search the edition, but it would help editors to understand our audiences better.17 We could learn about what people are looking for when they use our editions, which documents appeal most to them. I have always wondered whether users prefer to see the image of a document or a transcription, and wondered about whether advanced scholars actually do look at the image when conducting research. Are documents with difficult handwriting less likely to be used than those that are read more easily? How often do people consult the transcription guidelines when using an edition? Do they tend to prefer “sound-bite” documents that contain a short, strongly worded quote over longer more reasoned treatments of a subject? In which subjects are they most interested? Which document in our edition is most popular? By seeking feedback from our readers, we could learn far more about how they see the documents and annotations, in ways that are not possible with books. We could fine tune this data by gathering demographic information about our users as well. Armed with this knowledge, I am certain that we would learn important things. With such knowledge we might change the way we plan and create editions.

What, you might ask, makes people volunteer their time to contribute to such experimental sites? I believe it is the same thing that drives us: the appeal of our subjects, of working with these rich historical sources, and the feeling that one is contributing to something bigger. We study fascinating people who did interesting and important work, and the lure of participating in some way, whether as an intern, volunteer, or user on a Web site, will attract people if we invite them in. The students and interns who work on our projects get as much as they give, in terms of seeing the past in a different light. This immersion in the past personalizes history and historical actors in a way that other treatments, even biography, do not approach. You can tell from the kinds of questions our students ask that they are connecting to the subject in a different manner than they would by reading a textbook or watching a documentary.

Getting Dirty

One thing that the Internet teaches is that trying something new, even if it fails, is in most cases better than waiting for the perfect opportunity to come along. Every time we try something, we learn—whether we succeed or fail—and in many ways the risk of trying something new on the Web is smaller than it is using traditional publishing media. Yes, we will trip up sometimes, and yes, we might get dirty. But if we do not take chances and try out new and interesting ways of publishing documents, we will not be able to re-invent the edition for a new generation. In general, editors, myself included, have been too cautious about digitization. We are so concerned about selecting the perfect system for publishing our documents online, capturing all of their complexity, enabling other editions to be searched along with ours, and employing the best standards and chances of longevity, that we are almost afraid to act. Our funders are caught in the same trap. Both the Model Editions Partnership and the University of Virginia Press’s Rotunda digital imprint have been designed with the best of these goals, but while we have been trying to solve the questions asked of digital publishing in the 1990s and early 2000s, new questions have come up. In many senses those systems replicate the experience of using our editions in print format, with some nice searching added in. But they do not address the challenges of Web 2.0 technologies. They do not invite our users in or make their experiences with the documents a part of our edition. Taking care is important, but sometimes we move too slowly and miss out on the opportunities that new and changing media offer.

Is this something that we want to do? We will not know if we do not try it. Looking at Pepys again, I would say that there is much to admire there. If it had failed, if no one had read it, no one had commented on it or forwarded the link to their friends and colleagues, how much would Phil Gylford have lost? Some time, but that is about it. I am not suggesting that we abandon the work that we have traditionally published as print volumes, but I am suggesting that we can do more things with that work and with the research files that we all have in our offices. We publish only a tiny part of the knowledge and expertise that we gather in our work and it is time to take some chances, to try new things, and to risk some investment of time, against the chance that we can make a connection with the biggest audience that any of us will address. Because we do not have to get it right every time, but if we wait and wait to create the perfect digital edition that can meet every standard out there, we may find ourselves passed by.

We may fail, but even in that we will have learned more about how people use documents online. If even one crazy idea succeeds, it could change the playing field for scholarly editions.

1I would like to thank Esther Katz for her comments on an early draft of this speech, and for arguing with me about some of these ideas; it helped me enormously to sharpen this version. I would also like to thank Amanda French, the Digital Curriculum Specialist at NYU’s Archives and Public History Program, whose knowledge of and enthusiasm for these new technologies first started me thinking, and whose comments also helped enrich my speech. Lastly, thanks to my brother Mike Moran, author of several Web marketing books, including Do It Wrong Quickly: How the Web Changes the Old Marketing Rules(New York: IBM Press, 2008), who found a surprising number of parallels between the situation facing documentary editors and those faced by businesses in adapting to new forms of technology.

2See Paul Graham’s blog for a summary of the term’s changing meaning. http://www.paulgraham.com/web20.html.

3Andrew Keen, The Cult of the Amateur: how blogs, MySpace, YouTube, and the rest of today’s user-generated media are destroying our economy, our culture, and our values (New York: Doubleday, 2008), p. 3.

4See http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

5The site can be found at http://www.pepysdiary.com/. The Twitter site is: http://twitter.com/SamuelPepys.

6See the entry for Wednesday, 5 Sept. 1666 (http://www.pepysdiary.com/archive/1666/09/05/)

7For the Project Gutenberg text, see http://digital.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=4200.

8See The Complete Diary of Samuel Pepys (11 volumes), ed. by Robert Latham and William Mathews, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970–1983).

9For just two examples, see http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Diary_of_Samuel_Pepys and http://www.bibliomania.com/2/1/59/106/frameset.html; for a topic map of the diary, see http://www.techquila.com/pepysmap/html/.

10Thanks to Esther Katz for introducing me to this Internet phenomenon known as rickrolling. For those who have not seen the clip (and want to): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yu_moia-oVI.

11Robert Darnton, “Google & the Future of Books,” New York Review of Books, Volume 56, Number 2, Feb. 12, 2009 (http://www.nybooks.com/articles/22281 accessed Sept. 14, 2009).

12For the experiences of the American Historical Association, see Robert Townsend, “Mission, Media, and Risk: The American Historical Association Online,” AHA Perspectives, Dec. 2008 (http://www.historians.org/perspectives/issues/2008/0812/0812aha2.cfm).

13See Chapter 5 in Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations (New York: Penguin Press, 2008), pp. 109–42, for an insightful description of Wikipedia’s operations and organizing.

14“Wikipedia,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia (Accessed Oct. 8, 2009).

15Paul Graham, “Web 2.0,” November 2005 (http://www.paulgraham.com/Web20.html).

16For a sleepless night, read Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations, in which he describes the anti-expert quality of Web 2.0 as “about what happens when people are given the tools to do things together, without needing traditional organizational structures.” See his blog as well: http://www.herecomeseverybody.org/.

17For an interesting take on seeking user collaboration in museum settings, see Nina Simon’s Museum 2.0 blog entry, “Self Expression is Overrated: Better Constraints Make Better Participatory Experiences,” Mar. 16, 2009. (http://museumtwo.blogspot.com/2009/03/self-expression-is-over-rated-better.html). Simon argues that only a small percentage of museum goers are interested in reacting to exhibits by writing open-ended comments; far more participate when the collaboration is clearly defined and explained.