Jane Addams was an author with a fascinating and peculiar style. Her writing was all about her settlement work and social justice philosophy, but she had a delicate hand. She infused her philosophy with stories, weaving like lace her world view and ideas into the tapestry of the human drama and sometimes shocking socioeconomic realities she presented in her writing. I admire Jane Addams as a writer. In addition to publishing dozens of articles and pamphlets, she published eleven books in her lifetime. And it is my intention to own a first edition copy of every single one of them.

This is what I do. I embrace with wholeheartedness the historical subjects I study. I am no dispassionate historian, and I am always looking for tangible ways to connect with the past. As an editor, I always ground my analysis of history by the words on the pages of the historical documents with which I am so lucky to work. But I also know that weaving my historical enthusiasm into my scholarly writing, using threads from the connectedness I cultivate in my work, makes me a better historian. Perhaps, I, too, have a peculiar style.

Also like Jane Addams, I am a lover of books. My ever growing personal collection of 1,500-ish weighs heavy the bookcases in my modest 1919 bungalow. Like Jane Addams, I am an author, although my two books hold no candle to her eleven. Like Jane Addams, I also take great joy in owning, giving, and receiving books that matter to me. I appreciate Addams’s particular delight in collecting books associated with her friends and the people she admired. As Addams wrote the writer and editor Richard Watson Gilder in 1903: “The little book of Lincoln I knew very well but splendidly forgot that you had edited it. I need not say that I shall prize [it] more than before—which means a great deal.”

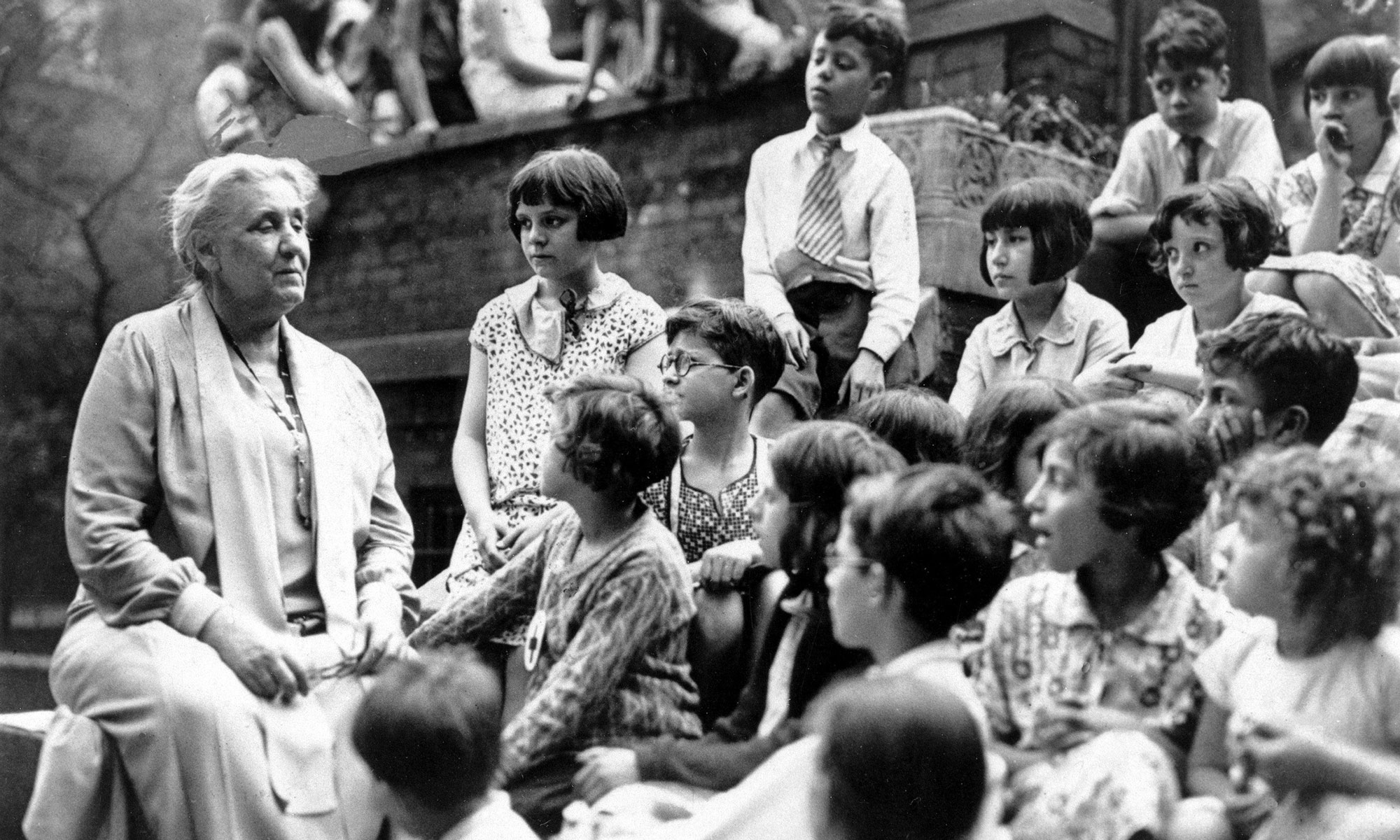

Having studied the papers of Jane Addams for four years now, I have come to see Jane Addams the woman as a distant friend. The project of collecting her books means a great deal to me. It feels a natural way to connect with her across the distance of the years between us. I am also drawn to Addams’s books because history has undervalued her contributions as an author. To most people who know of her, Jane Addams is Hull-House. She is a social worker and reformer. She is a campaigner for suffrage, for the short-lived Progressive Party, and for world peace. Indeed, all good and well deserved descriptions of her. Yet despite the fact that she published eleven books, she is rarely defined as an author, and with the exception of Twenty-Years at Hull-House, her books are not widely read or known today.

I am not a voice in the wilderness on the merits of Jane Addams’s literary significance. Her books are digitized on platforms like Internet Archive. Her writing inspired an excellent writer’s biography, Jane Addams: A Writer’s Life, and selections from Twenty-Years at Hull-House often appear in literary or historical anthologies. As well, in recent years, the University of Illinois Press has made her books more accessible, publishing them in paper with rich introductions to provide important historical contexts and bringing back into print the rarer among them.

Perhaps you, like so many people interested in the life and times of Jane Addams, have read one or more of the many biographies about her life. But have you read one of Jane Addams’s own books? If the answer is no, I encourage you to do so. To read her books is to know her better by seeing how she packaged her social reform knowledge for a wide audience. And, by the way, if it suits you to purchase a first edition copy in order to fulfil this imperative, and then if you find you have not the shelf space to accommodate it, I will happily take it off your hands.

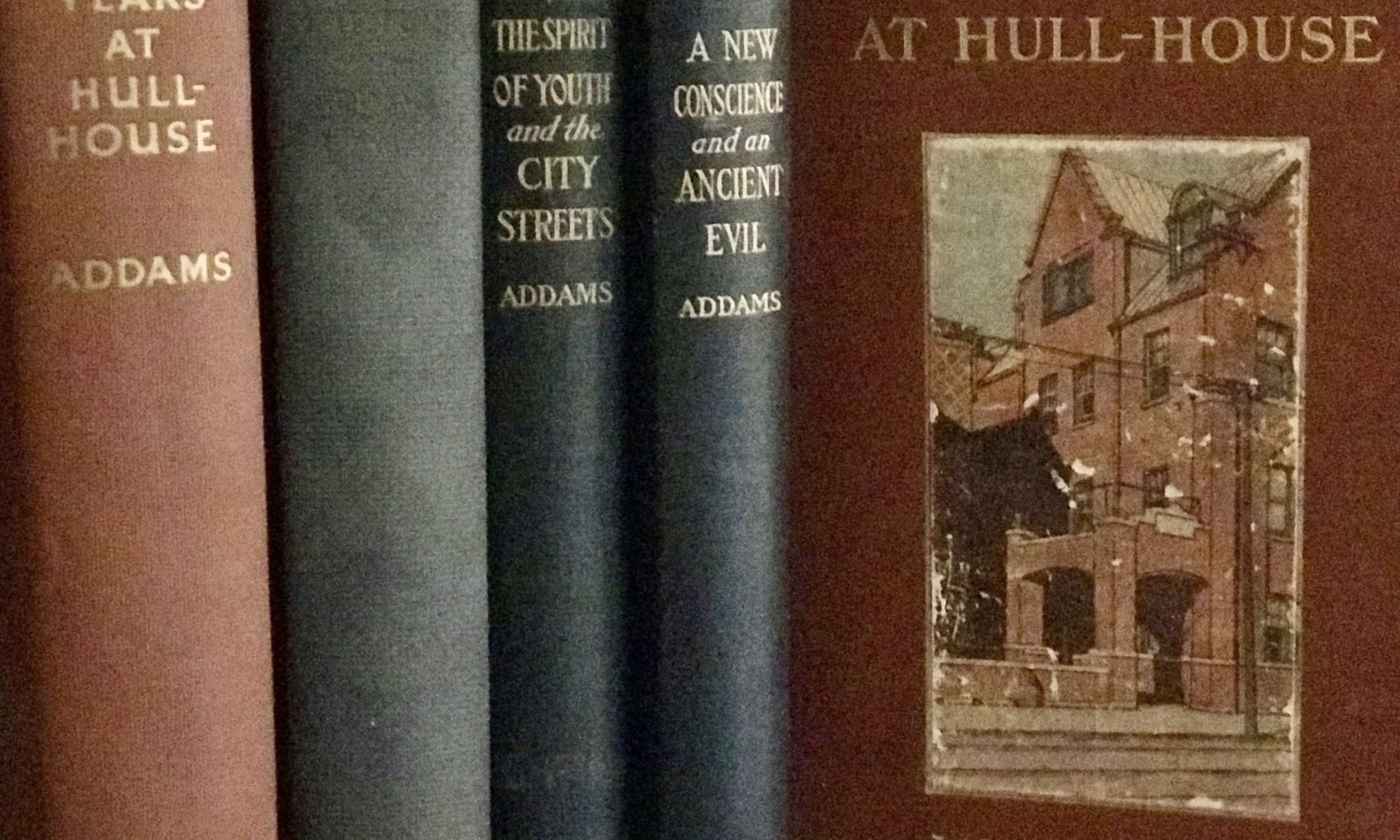

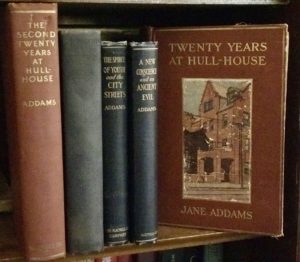

Thus far, I have collected five first editions in various states of condition. I have The Second Twenty-Years at Hull-House, My Friend, Julia Lathrop, The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil , and Twenty Years at Hull-House. The condition of my copy of Twenty Years at Hull-House is a bit rough, or, perhaps, I should say that it is delicate, like Jane’s soft employment of her bold philosophical ideas in her writing. No matter. It is my favorite, partly because of the lovely etching on the cover by Frank Hazenplug and the drawings scattered throughout by Norah Hamilton, both of these artists Hull-House residents. Because of their contributions to the book, Jane Addams wrote that it was “quite a Hull-House effort.” The book is quintessential Jane Addams, beautiful in its connections to the critical reform work she conducted in Chicago, to the settlement house that made her famous, and to the extraordinary people who lived and worked with her there.

and Twenty Years at Hull-House. The condition of my copy of Twenty Years at Hull-House is a bit rough, or, perhaps, I should say that it is delicate, like Jane’s soft employment of her bold philosophical ideas in her writing. No matter. It is my favorite, partly because of the lovely etching on the cover by Frank Hazenplug and the drawings scattered throughout by Norah Hamilton, both of these artists Hull-House residents. Because of their contributions to the book, Jane Addams wrote that it was “quite a Hull-House effort.” The book is quintessential Jane Addams, beautiful in its connections to the critical reform work she conducted in Chicago, to the settlement house that made her famous, and to the extraordinary people who lived and worked with her there.

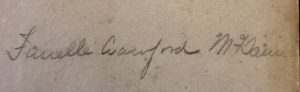

Inside my copy of Twenty Years at Hull-House is the name, written in pencil, of the woman whom I suspect was the book’s first owner. Fanell Crawford McDaniel. She was a former teacher, trained at the Normal School in St. Louis, who was a 33-year-old homemaker in 1910 or early 1911 when she purchased the book and when she was the wife of a prominent attorney in Tuscaloosa,  AL. I lived in St. Louis for eight years, and one of my dearest friends in the world was born and raised in Tuscaloosa. The spine may be broken on my affordable first edition of Twenty-Years, but possessing it connects my heart to Jane, to Fanell, and to my friend Christi in ways that make it more prized than a more pristine but less loved copy of Addams’s most well-known book might be.

AL. I lived in St. Louis for eight years, and one of my dearest friends in the world was born and raised in Tuscaloosa. The spine may be broken on my affordable first edition of Twenty-Years, but possessing it connects my heart to Jane, to Fanell, and to my friend Christi in ways that make it more prized than a more pristine but less loved copy of Addams’s most well-known book might be.

I am content to take time in the acquisition of the remaining six of Jane Addams’s books. It is a fun process this state of collecting, and I don’t want to reach its end too soon. I know the first two books, Democracy and Social Ethics and Newer Ideals of Peace, are more rare and will come at dearer prices. Last week I almost pulled the trigger on a copy of Democracy, but its raggedy condition bid me pause to think it over for a while. There is a fine copy of the Chautauqua Reading Series edition of Newer Ideals available for $24, which is intriguing. I might purchase that one soon, although it would be an addition and not a replacement of the original edition I desire.

Right now, I also have my eye on a first edition of The Excellent Becomes the Permanent. I hope one of the books I collect will have an inscription by Jane Addams. This copy of The Excellent would check that box in glorious fashion. It is inscribed by Addams to her English friend Stanton Coit, a leader in the Ethical Culture Movement. The book is in the UK, and its list price of $360 will make it my most expensive acquisition yet. The shipping costs alone will top the bargain price I paid for my first edition copy of My Friend, Julia Lathrop. I wonder if this might be my best and least expensive chance for a signed Jane Addams original, but I don’t know enough about the market to deem my hesitation a gamble.

On one of the bookseller websites I monitor there is a first edition, second printing of The Long Road of Woman’s Memory. Not the first edition I seek, but it is desirable for its lengthy inscription: “With all good wishes from ‘the author’ Jane Addams Hull-House Chicago.” Sigh. Heavy sigh. The list price of that dandy is $2,500. Free shipping, but still beyond the budget of this historian.

Maybe I should order that $360 book in the UK and count my first-edition-Jane-Addams-book blessings.

Stacy Lynn, Associate Editor

Sources: Katherine Joslin, Jane Addams: A Writer’s Life (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004); “Stanton Coit” (1857-1944), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; “James Watson Gilder” (1844-1909), American National Biography; 1900 U.S. Federal Census; 1920 U.S. Federal Census; “A Charming Teacher,” Tuscaloosa (AL) Gazette, July 9, 1896, 3; Wedding Notice, Tuscaloosa News, Nov. 10, 1903, p. 5; Jane Addams to Richard Watson Gilder, April 6, 1903; Jane Addams to Graham Taylor, September 4, 1910, all in Jane Addams Digital Edition.

Below is the impressive book bibliography of Jane Addams, the oldest books with links to a version of them on the internet. It is Women’s History Month, you know, so why not celebrate by reading a book by a great American writer?

Democracy and Social Ethics (1902)

Newer Ideals of Peace (1907)

The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets (1909)

Twenty Years at Hull-House with Autobiographical Notes (1910)

A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil (1912)

The Long Road of Woman’s Memory (1916)

Peace and Bread in Time of War (1922)

The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House (1930)

The Excellent Becomes the Permanent (1932)

My Friend, Julia Lathrop (1935)

Forty Years at Hull-House (1935)

A scholarly editor and historian, Stacy Lynn formerly edited the papers of Abraham Lincoln and currently is an editor at the Jane Addams Papers Project.