This is a guest post by Marilyn Fischer, Professor Emerita at the University of Dayton, who specializes in political philosophy and American pragmatism. She has edited Jane Addams’s writings on peace and is the author of Jane Addams’s Evolutionary Theorizing: Constructing Democracy and Social Ethics (2019). She is currently working on two additional volumes that examine Jane Addams’s writings. She is a member of the Jane Addams Papers Advisory Board.

If you want to know how Addams wrote her books, ask her relatives. Her nephew, James Weber Linn, tells us Addams would begin with her speeches, and then revise, expand, or contract the material into a coherent whole.[1] Addams’s niece, Marcet Haldeman-Julius, reminisced, “I can still hear my mother’s infectious laugh as she watched Aunt Jane initiate me into her method of ‘pins-and-scissors’ writing.”[2] Addams would have loved word processing software. Copy and paste is so much simpler than scissors and pins.

If you want to know how Addams wrote her books, ask her relatives. Her nephew, James Weber Linn, tells us Addams would begin with her speeches, and then revise, expand, or contract the material into a coherent whole.[1] Addams’s niece, Marcet Haldeman-Julius, reminisced, “I can still hear my mother’s infectious laugh as she watched Aunt Jane initiate me into her method of ‘pins-and-scissors’ writing.”[2] Addams would have loved word processing software. Copy and paste is so much simpler than scissors and pins.

Does it matter how Addams wrote her books? There are many ways to interpret a text. One can compare Addams’s ideas to those of John Dewey or Charlotte Perkins Gilman or even Dorothy Day. One can ask if Addams’s ideas are still relevant today to solving environmental problems, revitalizing democracy, ending discrimination against women, immigrants, the poor, or the disabled. These are all worthy uses of Addams’s ideas, and have been carried out without considering how Addams constructed her texts. Yet, knowing the characteristics of Addams’s speech-making can also shift readers’ interpretations of her written texts, and is thus worth examining.

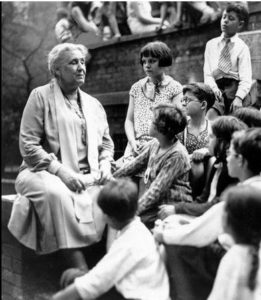

Addams gave thousands of speeches in Chicago and on lecture tours throughout the country and abroad. Her public reputation rested in large part on her speeches.[3] Manuscripts of some of her speeches are in the digital archives and the Jane Addams Papers Microfilm edition. From early in her career, Addams’s speeches were widely covered in the national press and throughout the English-speaking world. This was a world on which the sun never set, as the British Empire was at its height. News coverage typically included lengthy excerpts of what she said. Sometimes Addams spoke for up to an hour; often she shared the platform with multiple speakers who were each allotted a mere ten minutes. Addams’s challenge was to engage the audience so they didn’t fall asleep or walk out, while saying something substantive enough to provoke new ways of thinking and imagining. Here I focus on three characteristics of Addams’s speech-making with which she engaged her audiences: orality, compression, and “circling round and spiraling out.” She carried these techniques into her written articles and books.

Orality: Consider how Addams’s initial audiences heard her and the spaces in which she spoke. These ranged from intimate gatherings of a few dozen, to packed auditoriums that seated thousands. At the time, before radio and television, commentators spoke of the power of public addresses as “a mystical form of electricity.”[4] The electricity began with the speaker, whose diction, movements, and tones amplified her words’ meanings. Its power went out to the audience who felt its voltage reverberate in others’ murmurs, cleared throats, cheers, or hoots.[5] Hearing is intimate, as another’s voice enters one’s own body.[6] As a result, speaker and audience think and feel and respond together, all at once.

The age of eloquence and oratory had not yet closed.[7] Public addresses educated, entertained, and built—or maybe fractured—communities, all at the same time. Addams’s audiences took part in many of these practices. They participated in religious revivals, attended politicians’ hours-long debates, and cheered or booed labor agitators. They were practiced at listening to and absorbing eloquent speech. Students memorized poetry and great speeches; their repertoire could include thousands of lines of poetry and orations.[8] Addams was ready for them. She had studied oratory and rhetoric in college, when, as historian Carolyn Eastman notes, “training in oratory was indistinguishable from training as an actor.”[9] In college, Addams was on the debate team and participated in oratory contests.[10] Because Addams constructed her books around her speeches, we can think of her books as “undelivered speeches,” best approached through the ear, as well as the eye.[11]

Addams’s audiences felt her power. Of her talk, “Philanthropy Won’t Do,” the reporter for the Indianapolis Journal wrote, “Miss Addams’s personality is an immediate bid for the interest of an audience; and the sympathy in her face, voice and manner would warm the cockles of the most unaltruistic heart.”[12] The Times of Oswego, New York reported that no one was bored by Addams’s hour-long talk on settlements, stating, “She is a fluent speaker, with a crisp, vigorous, incisiveness of style that makes her speech a delight; and her broad culture, warm humanitarianism and keen insight into social problems impart a most convincing air to her words.”[13] Addams used her presence on stage to create relations with her audiences that would engage their emotions and imaginations, as well as their intellects.[14]

Speech is more powerful when it is vivid and concrete. Addams used stories to accomplish this. Now she could cite statistics as well as any sociological data-collector, and she usually tucked several of them into her texts. But statistics send little electricity from speaker to audience. Addams clothed the data with faces and bodies in particular situations. Addams did not begin her speech, “Child Labor and Pauperism,” with a catalog of data, or even with scenes inside exploitive workplaces. She began by placing her listeners where they often were, on the streetcar at six p.m., as men, women, and children poured out of factories at end of shift. Addams remarked, “The boys and girls have a peculiar hue, a color so distinctive that any one meeting them on the street even on Sunday in their best clothes and mixed up with other children who go to school and play out of doors, can distinguish almost in an instant the children working in factories. There is also on their faces a something indescribable, a premature anxiety and sense of responsibility which we should declare pathetic if we were not used to it.”[15] Her audience members had likely seen these children often, without ever really seeing them. The story startled them into recognizing that evidence of child exploitation was all around them, written on the faces of children they saw.

Addams aimed deeper than to increase her audiences’ sense of duty toward others. She aimed to change their fundamental moral and perceptual sensibilities, their ways of perceiving the world and themselves, and of their sense of relationship with others. These sensibilities are the soil out of which opinions and duties grow, or wither. Commenting on a speech by suffragist Anna Howard Shaw, Addams said, “It was a wonderful lesson in speech-making, not to desire to make an exposition of what you believed or did not believe, but absolutely to persuade your audience from one point of view, if you possibly could, to another point of view.”[16] For Addams to do this, she needed to enter each audience’s mode of perception, and use what they knew and valued and believed, so as to open them to others ways of knowing, valuing and believing. Appealing to their emotions, their sympathies, and imaginations was just as important as appealing to moral codes or their capacities for logical reasoning.

Knowing all this complicates the interpretive task for scholars today. We read Addams’s writings to find out what she thought. Her writings contain her thoughts, but not directly. A good example is the opening paragraph of her widely read essay on suffrage, “Why Women Should Vote.”[17] Addams begins by stating how people had long believed that a woman’s “paramount obligation” was to the home, and that was unlikely to change.[18] Recent scholars have used that statement to locate Addams in the maternalist, conservative wing of suffrage advocates.[19] However, good rhetor that she was, Addams began her talks by identifying common ground with her audience, and using that as a springboard to lead them to different ways of imagining the world. Addams wrote “Why Women Should Vote,” for the Ladies Home Journal, the most widely read magazine in the U.S. at the time. Its primary audience was middle and lower-middle class women, generally homemakers, and likely opposed to women’s suffrage, who saw women’s place as in the home, not in the dirty world of politics.[20] Addams didn’t lie; but she made her opening statement capacious enough that most everyone could find room for themselves inside it.[21] She then led her readers step by step into the lived realities of women like her immigrant neighbors who desperately needed the vote in order to provide their families with clean water, untainted food, and streets that were not fouled with garbage.

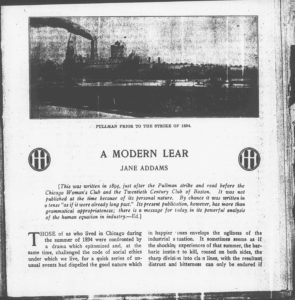

Compression: The second characteristic of Addams’s speech-making and writing, is compression. When speakers have only a short time to be substantive, what do they do? They leave out whatever they can, and rely on the audience to fill in the gaps. Because Addams and her audiences lived at the same time and place, they shared a great number of associations. The briefest mention could bring all that to mind. When Addams addressed an anti-imperialism protest rally in April 1899, she could simply say, “We suddenly find ourselves bound to an international situation.”[22] She did not need to tell the audience that the U.S. was deep in the muck of the Philippine-American War, or that the U.S. economy and their own economic well-being were deeply dependent on international trade, or that the navies of the European imperial powers were hungrily circling the Philippines, in case the U.S. should pack up and leave.[23] To Addams, these facts made the typical response of others in the American Anti-Imperialist League untenable, as they counseled the U.S. to just pull out.[24] Regardless of what the U.S. did with the Philippines, it would still be entangled in the international situation. And when Addams threw in the line, “Government is not something extraneous, consisting of men who wear gold lace,” her audience immediately knew she was mocking British and American imperialism.[25] At the time, the amount of gold lace on a military uniform marked the wearer’s rank. This was a sign of hierarchy and on order maintained by force, rather than through democratic egalitarianism. Addams’s image, now obscure, was a potent element in her protest against the U.S. becoming an imperial power.

Compression gives space for the audience to think along with the speaker. Alexander Bain, author of Addams’s college rhetoric and composition text, praised brevity and devoted a whole chapter to how to achieve it.[26] He included the pointer that “things well-known [can be] recalled by brief allusion.”[27] Bain also stressed the power of indirect speech noting, “The device of suggesting, instead of openly expressing, . . . give[s] a starting-point to the thoughts.”[28] Compression engages listeners’ and readers’ imaginations to fill in what is omitted. They become active participants in the event, rather than passive receptors. In effective speech-making, “nailing it down” is a weakness, not a strength.

Compression is a technique used by literary writers and especially by poets, the most aural of literary artists. Addams’s writings were considered poetic. A portrait of Addams in Collier’s National Weekly notes, “She writes hardly a paragraph but is shot through with poetry.”[29] Settlement resident, Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch, wrote in her review of The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets for Political Science Quarterly, “Miss Addams’s recent book continues the note of realism suffused with imagination which characterizes all her utterances, whether oral or written. . . . [It] is her most lucid and poetical expression.”[30] If this be true, then Addams’s writings should be approached as works of art, as much as works of philosophical and sociological analysis.

Circling Round: The final characteristic of how Addams spoke and wrote I’ll call “circling round and spiraling out.” The image comes from William Hard, a journalist with the Chicago Tribune who heard Addams’s convocation address at the University of Chicago. He wrote to her, “I seemed to stand in the center of the subject and to revolve slowly round with a philosopher at my side.”[31] James Weber Linn, Addams’s nephew, commented that among the clashing opinions held by the many strong characters residing at Hull House, “only Jane Addams, perhaps, [could see] everything from everybody’s point of view.”[32]

Addams turned circling round into a style of speaking and writing. She could circle round multiple viewpoints in a brief paragraph, a chapter, or an entire book. Because Addams primarily addressed white, middle-class audiences, the demographic to which she herself belonged, she did not have the credibility, or “ethos,” as Aristotle called it, to denounce white, middle-class conventions as Ida B. Wells-Barnett or Frederick Douglass did, both of whom were born enslaved.[33] By circling round, though, Addams could spell out the hypocrisies of the people she was addressing. She demonstrates this in her speech, “Child Labor and Pauperism,” mentioned above. Addams uses this topic to charge her middle-class audiences with grotesque levels of moral irresponsibility. The cumulative weight of her circlings is far heavier and more densely layered than saying, “Those poor children. Let’s help them.”

Addams does this by identifying herself with the audience, “we” do this, “we” neglect that. On each circling round, she inserts personal stories and research data to demonstrate the following stack of conclusions: 1) Child labor robs the future of what belongs to it—the potential future strength and capacities of today’s children. 2) Today’s child laborers are tomorrow’s paupers—adults incapable of holding a job who must depend on agencies and local governments to support them. Addams reinforces her claim with the salvo, “No horse trainer would permit his colts to be so broken down.” 3) By allowing industries to underpay children and adults, you allow your industries to be “parasitic on the future of the community,” creating “the pauperization of society.” 4) Finally, child labor “pauperizes the consumer” (i.e., her audience members), by flipping the roles of giver and recipient of charity. For, as she states in the most personal of tone: “If I wear a garment . . . for which the maker has not been paid a living wage . . ., then I am in debt to the woman who made my cloak. I am a pauper and I permit myself to accept charity from the poorest people of the community.” All of this, Addams charges, “debauches our moral sentiment, it confuses our sense of values.”[34] By noting Addams’s circling round, one sees that Addams’s speeches say less about the ostensible topic of child labor and pauperism, than builds a case, step by step, for middle-class Americans’ utter failure to take responsibility for the kind of society they live in.

In some passages the compressing and the circling round happen so fast, today’s readers hardly see it. In The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, a book largely derived from speeches, Addams gives a vivid portrait of young adolescent girls giggling as they walk down the street, wearing “preposterous clothing.” One has on a “huge hat, with its wilderness of bedraggled feathers.”[35] Why, one might ask, is Addams bothering about adolescent fashion? Why is she being so stuffy and moralistic? First, the compression: Addams omits to say what her readers already knew, that concerned citizens immediately identified the huge hat as advertising the girl’s sexual availability, and the fact that she walked down the street unchaperoned was a sure sign she was looking for johns.[36] Instead of sharing the moralistic concerns of these citizens, Addams uses the hat as a device to lay a heavy charge against them.

Immediately before describing the girl with the hat, Addams mentions the “unrestrained jollities of restoration London” that broke out as soon as “the soldiers of Cromwell shut up the people’s pleasure palaces.”[37] She didn’t need to tell her readers that the mid-seventeenth century “jollities” were disastrous days of chaos and disorder that broke out just after Oliver Cromwell (literally) lost his head. Addams immediately followed her description of the hat with its bedraggled feathers, saying, “the variation from the established type is at the root of all change,” an allusion to Darwin’s theory of how new species are generated. She quickly adds, “It is only the artists who see these young creatures as they are—the artists who are themselves endowed with immortal youth.”[38] This was a common trope, that artists have privileged access to reality’s underlying truth.

Addams, without being pedantic, uses the girl with the hat to celebrate adolescent sexual energy as a fount of renewal for a society grown weary. By circling round the hat, she uses the collective weight of history, biology, and artistry to chastise concerned citizens for wanting to suppress a vital source of life. By leaving her texts incomplete, Addams invites her readers to construct them with her. And they—the texts and the readers—are more powerful because of it.

Does all of this matter? To better interpret Addams should we start listening to audiofiles of Addams’s speeches and writings, uncompress her passages, and map her circlings round? I think it does matter, though more for some questions than others. To begin with, following these patterns reveals Addams’s character. She had a rapier wit, a delicious sense of irony, and at times was blazingly sarcastic. All of that is right there, on the page, though seldom seen.

Many people today are interested in Addams because they see her activism and her ideas as resources for bringing about social change. Addams was a first-rate public intellectual. Addams’s attention to selecting her vocal register, vocabulary, images, and examples so as to communicate most effectively with each specific audience she addressed is a worthy model to emulate.

Finally, attending to Addams’s use of orality, compression, and circling round leads to profound interpretations of Addams’s thought that are otherwise missed. Hearing Addams speak as well as studying what she wrote will enable us to enter into her thought and life more deeply.

—Marilyn Fischer

——————-

[1] Linn, Jane Addams, 116.

[2] Marcet Haldeman-Julius, Jane Addams as I Knew Her, 16.

[3] Louise W. Knight, “An Authoritative Voice,” 221; Linn, Jane Addams, 242.

[4] Eastman, “Conclusion: Placing Platform Culture,” 187.

[5] Eastman, “Conclusion: Placing Platform Culture,” 187.

[6] John Dewey made this point, writing, “The connections of the ear with vital and out-going thought and emotion are immensely closer and more varied than those of the eye. Vision is a spectator; hearing is a participator” (The Public and Its Problems, 371.)

[7] See Stob, William James and the Art of Popular Statement, Chapter 1.

[8] Eastman, “Conclusion: Placing Platform Culture,” 190-191.

[9] Eastman, “Conclusion: Placing Platform Culture,” 191.

[10] Knight, Citizen, 87, 95, 98.

[11] The notion of an “undelivered speech” comes from Arnold, “Oral Rhetoric, Rhetoric, and Literature,” 170.

[12] “Philanthropy Won’t Do.”

[13] “Settlement Work and Its Results.”

[14] In other words, Addams made use of ethos, pathos, and logos, as called for in classical rhetoric.

[15] Addams, “Child Labor and Pauperism,” 115.

[16] Addams, “Address on Anna Howard Shaw,” 7.

[17] A google search for “Why Women Should Vote” shows that it is still widely read today, as it is posted on many history websites and academic websites.

[18] Addams, “Why Women Should Vote,” 21.

[19] For scholars who regard Addams as a maternalist, and among the more conservative of the suffrage advocates, see Schultz, “Introduction,” xli; Mink, The Wages of Motherhood, 1-13. Nackenoff claims that Addams used maternalist rhetoric for strategic reasons (“New Politics for New Selves,” 131). Hamington regards “Why Women Should Vote” as “the most conservative of her appeals for women’s enfranchisement” (The Social Philosophy of Jane Addams, 69).

[20] Waller-Zuckerman, “‘Old Homes, in a City of Perpetual Change,’” 717.

[21] Addams was following the principle articulated by Bain, “As in argument, so in oratory generally, there must be some common ground to work upon” (English Composition and Rhetoric, 214). Addams’s introduction and line of argument in “Why Women Should Vote” is startlingly different from the ones she used in suffrage addresses to very different audiences. See “Women’s Clubs and Public Policies,” an address to the General Federation of Women’s Clubs; and “The Larger Aspects of the Woman’s Movement,” for the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

[22] Addams, “Democracy or Militarism,” 35-36.

[23] For a succinct summary of the Spanish-American War and the war in the Philippines, see Herring, The American Century and Beyond, 11-31; Trask, “Introduction”; see also Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues, 97, 221-234, 241-247.

[24] For a discussion of the Anti-Imperialist movement see Tompkins, Anti-Imperialism in the United States. For transcripts of the speeches given with Addams’s address, see The Chicago Liberty Meeting. Addams’s address, “Democracy or Militarism,” is on pp. 36-39.

[25] Addams, “Democracy or Militarism,” 38.

[26] Bain, English Composition and Rhetoric, 66-73.

[27] Bain, English Composition and Rhetoric, 67.

[28] Bain, English Composition and Rhetoric, 62.

[29] “Portrait of a Woman,” 11.

[30] Simkhovitch, Review of The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, 555.

[31] William Hard to Jane Addams, January 15, 1905.

[32] Linn, Jane Addams, A Biography, 135.

[33] Bryan, Slote, and Angury, The Jane Addams Papers: A Comprehensive Guide, 95; Knight, “Looking In from the Outside.”

[34] Addams, “Child Labor and Pauperism.”

[35] Addams, The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, 8.

[36] The Chicago Vice Commission included several examples of girls engaging in sexual acts in order to buy hats costing many times their weekly salaries. See Vice Commission of Chicago, The Social Evil in Chicago, 78, 204, 210.

[37] Addams, The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, 7.

[38] Addams, The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets, 8, 9.

References

References

Addams, Jane. “Address on Anna Howard Shaw,” Nov 13, 1919, typed manuscript, digital edition.

Addams, Jane. “Child Labor and Pauperism.” National Conference of Charities and Correction, Proceedings (1903): 114-21. Digital edition.

Addams, Jane. “Democracy or Militarism,” in The Chicago Liberty Meeting, 35-39. Chicago: Central Anti-Imperialist League, 1899.

Addams, Jane. “The Larger Aspects of the Woman’s Movement.” American Academy of Political and Social Science, Annals 56 (1914): 1-8. Digital edition.

Addams, Jane. The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets. New York: Macmillan, 1909.

Addams, Jane. “Why Women Should Vote.” Ladies Home Journal 27 (January 1910): 21-22. Digital edition.

Addams, Jane. “Women’s Clubs and Public Policies,” General Federation of Women’s Clubs. Biennial Convention Official Report (1914): 24-30. Digital edition.

Arnold, Carroll C. “Oral Rhetoric, Rhetoric, and Literature.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 40 (2007): 170-187.

Bain, Alexander. English Composition and Rhetoric, a Manual. American Edition, Revised. New York: D. Appleton, 1867.

Bryan, Mary Lynn McCree, Nancy Slote, and Maree De Angury, editors. The Jane Addams Papers: A Comprehensive Guide. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996.

Chicago Liberty Meeting. Chicago: Central Anti-Imperialist League, 1899.

Dewey, John. The Public and Its Problems. 1927. In John Dewey: The Later Works: 1925-1953: vol. 2, edited by Jo Ann Boydston. 235-372. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1988.

Eastman, Carolyn. “Conclusion: Placing Platform Culture in Nineteenth-Century American Life.” Thinking Together: Lecturing, Learning, and Difference in the Long Nineteenth Century, edited by Angela G. Ray and Paul Stob. 187-201. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University, 2018.

Haldeman-Julius, Marcet. Jane Addams as I Knew Her. Girard, KS: Haldeman-Julius Publications, 1936.

Hamington, Maurice. The Social Philosophy of Jane Addams. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Hard, William to Jane Addams, January 15, 1905. Digital edition

Herring, George C. The American Century & Beyond: U.S. Foreign Relations, 1893-2014. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917. New York: Hill and Wang. 2000.

Knight, Louise W. “An Authoritative Voice: Jane Addams and the Oratorical Tradition.” Gender & History 10 (August 1998): 217–251.

Knight, Louise W. “Looking In from the Outside, or A Few Angles on Rhetoric and Change.” Rhetorics Change/Rhetoric’s Change, edited by Jenny Rice, Chelsea Graham, and Eric Detweiler. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press and Intermezzo, 2018. (an ePub; no pagination)

Knight, Louise W. Citizen: Jane Addams and the Struggle for Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Linn, James Weber. Jane Addams: a Biography. 1935. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Mink, Gwendolyn. The Wages of Motherhood: Inequality in the Welfare State, 1917-1942. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Nackenoff, Carol. “New Politics for New Selves: Jane Addams’s Legacy for Democratic Citizenship in the Twenty-First Century.” in Jane Addams and the Practice of Democracy, edited by Marilyn Fischer, Carol Nackenoff, and Wendy Chmielewski, 119-142. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

“Philanthropy Won’t Do.” Indianapolis Journal, July 5, 1900, p. 3.

“Portrait of a Woman,” Collier’s: The National Weekly 43 (April 10, 1909): 11.

Schultz, Rima Lunin. “Introduction.” In Women Building Chicago, 1790-1990: A Biographical Dictionary edited by Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast. xix-lx. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

“Settlement Work and Its Results.” Times (Oswego, New York), March 28, 1905, Jane Addams Papers Microfilm, reel 55, frame 1306.

Simkhovitch, Mary Kingsbury. “Review of The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets. Political Science Quarterly 25 (Sept 1910): 555-556.

Stob, Paul. William James and the Art of Popular Statement. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2013.

Tompkins, E. Berkeley. Anti-Imperialism in the United States: The Great Debate, 1890-1920. Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press. 1970.

Trask, David F. “Introduction.” The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, edited by Spencer C. Tucker. xxix-xxxiii. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 2009.

Vice Commission of Chicago. The Social Evil in Chicago: A Study of Existing Conditions with Recommendations by The Vice Commission of Chicago. Chicago: The Vice Commission of Chicago, Inc., 1911.

Waller-Zuckerman, Mary Ellen. “‘Old Homes, in a City of Perpetual Change’: Women’s Magazines, 1890-1916.” The Business History Review 63 (Winter, 1989): 715-756.

Cathy Moran Hajo is the Editor and Director of the Jane Addams Papers Project at Ramapo College of New Jersey. She is an experienced scholarly editor, having previously worked for over 25 years as Associate Editor at the Margaret Sanger Papers at New York University. Dr. Hajo received her Ph.D. in history from New York University in 2006, and is addition to her work on the Sanger Papers, published “Birth Control on Main Street, Organizing Clinics in the United States, 1916-1940,” in 2010.

Her teaching interests include scholarly editing and digital history, and she currently teaches for the Institute for Editing Historical Documents, the Digital Humanities Summer Institute. She teaches a digital history course at Ramapo College.

Jane Addams attended Rockford Female Seminary and was among the first class to receive a Bachelors degree. At Rockford she honed skills that would later be used in her career as the founder of Hull House, leader of the Suffrage, Settlement and Peace movements and her literary career as author of 11 books and hundreds of journal and magazine articles. At Rockford she was the Valedictorian, Editor of the school newspaper, President of the Debate Club and President of her class.

Jane Addams attended Rockford Female Seminary and was among the first class to receive a Bachelors degree. At Rockford she honed skills that would later be used in her career as the founder of Hull House, leader of the Suffrage, Settlement and Peace movements and her literary career as author of 11 books and hundreds of journal and magazine articles. At Rockford she was the Valedictorian, Editor of the school newspaper, President of the Debate Club and President of her class.