In 1908 when Jane Addams was speaking at a dinner in Chicago, she expressed her frustration with women who ridicule suffragists:

There are women who will laugh at us for our interest in the ballot, and who will then give absorbed hours, in the privacy of their rooms, to great electrical massage machines, face-steaming engines, curious masks and huge flesh-reducing mechanisms. An elderly woman of this type, after an afternoon’s struggle with all sorts of beautifying devices, dyed her hair a bright gold. “Do you think it makes me look younger?” she asked me. “Yes,” said I. “About three weeks.” — Jane Addams’s Retort, June 7, 1908, Jane Addams Digital Edition (JADE).

Jane Addams had a sense of humor, but she rarely made such public jibes as she did in telling this story, which was reported in newspapers across the country. It is understandable, however, that the frivolous, gold-haired woman mocking the suffrage movement would annoy her. Jane Addams was a serious woman who devoted her time to making the world a better place; she had no time to worry that her hair was turning gray and that lines were forming on her face. In fact, it was her assertion that as the social health of the nation was concerned “gray-haired women” needed to “become a part of it.”

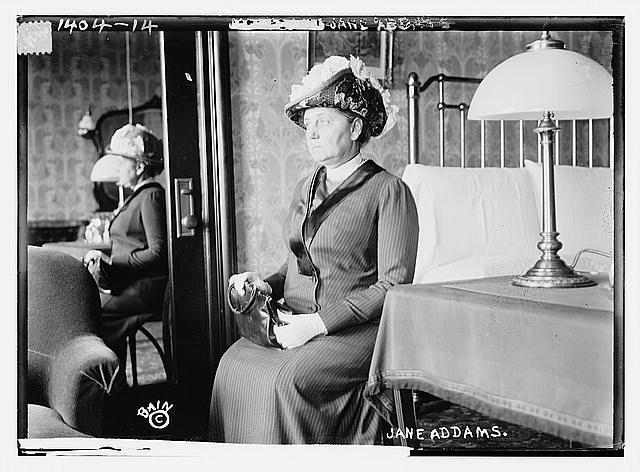

By personality in 1908 Jane Addams wanted to appear to the world as a well-groomed, modest, serious woman in sensible shoes. Yet it is also true that Jane Addams likely curated a persona designed to make her a credible witness to the social ills she sought to remedy, to make the public feel at ease with her, and to convince people in power to be more open to her ideas. She struck a brilliant balance that allowed her to be approachable to her working-class Hull-House neighbors and to fit in among her middle-class peers and wealthy patrons. She dressed to blend in, not to stand out; she presented a gentle, serious, thoughtful demeanor in order to convey authority.

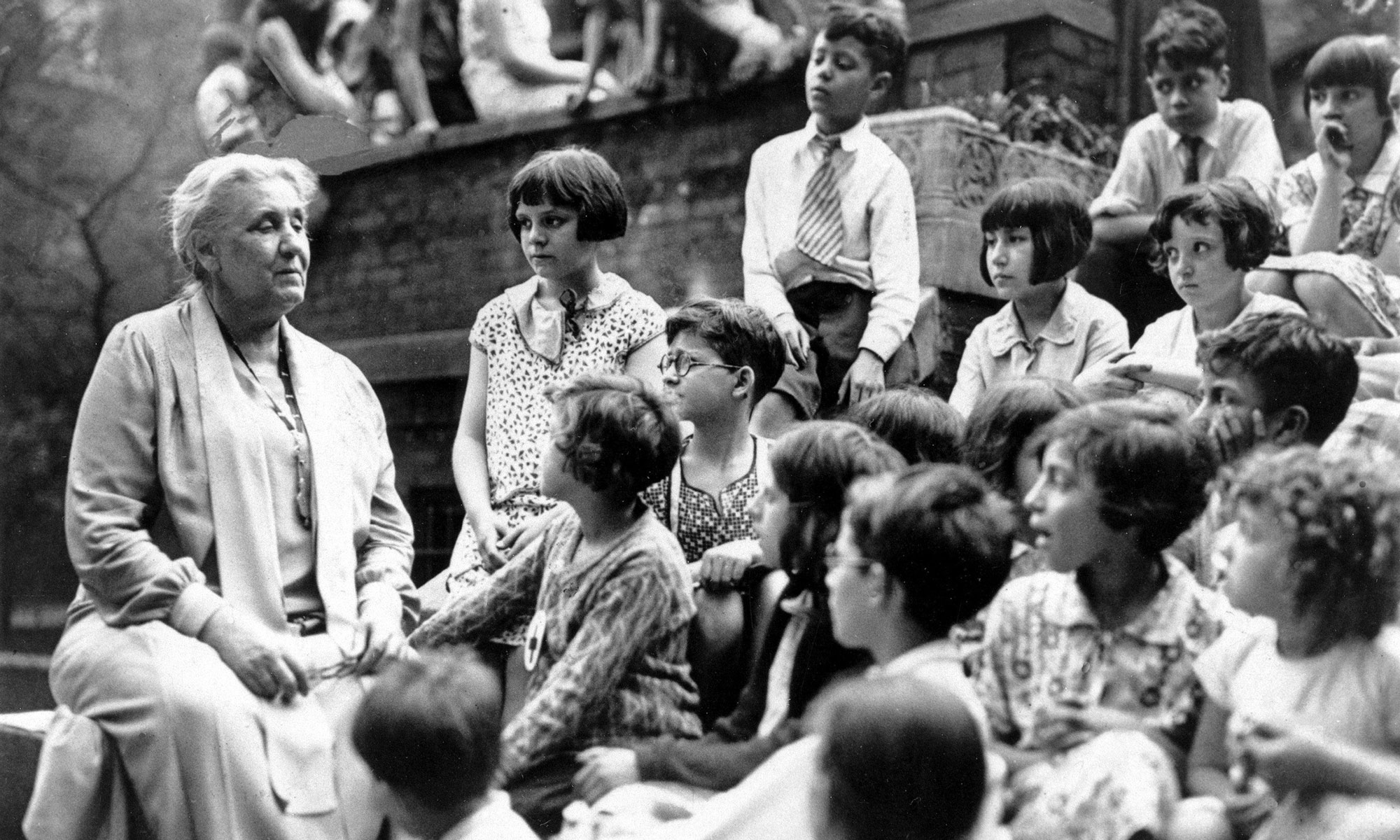

She was simply dressed. Her attire was a soft gray in deep harmony with the woman. Her hair was combed straight back from her high forehead, and made into a knot on the back of her head. Her eyes are large and soft, and continually there is a little light flickering in them, which seems to bid children welcome to her side. She radiates kindness and a big heart’s offerings would inspire any child to do better. — Dedication of Bomberger Park, June 30, 1908 (The Dayton Herald), JADE.

What this large and visibly impressed crowd saw was a woman of medium height, with hair well streaked with gray, and dressed in a plain dark dress relieved only by a white lace collar. In a clear, well-modulated voice that carried to every corner of the room she started in, without preliminaries, to tell the story of the condition of the starving children of the European countries. — Feed the World and Have a League of Nations, February 19, 1921 (Rochester Democrat and Chronicle), JADE.

Recently, I read a 1915 Washington Times interview with Jane Addams, which at first made me start and then made me consider this idea that Jane Addams wore a mask she designed for the successful female Progressive reformer she became. Florence Yoder, the young journalist conducting the interview, who was perhaps wearing her own mask as a woman in a newspaper world of men, described Addams this way:

Unlike any other person in the world whom we have ever seen, Miss Addams regulates her facial expressions by exactly the opposite method employed by the average person. When speaking of something in which she is very much interested, there is little or no animation, her face becomes a mask, she looks in one direction only, glancing occasionally full into the eyes of the listener. Her voice is pitched very low, almost a monotone, yet one never misses a word. Then when something trivial comes up, something of almost childish interest, her face brightens she relaxes into a smile, and the mask does not slip on again until the more serious subject is revived. It is almost as if she were trying to subjugate her own personality entirely, eliminate herself entirely from the discussion, and let only the ideas with which she wishes to impress her listener, register on the brain. — Interview with Florence E. Yoder, Jan. 8, 1915 (Washington Times), JADE.

Until I read that description of her, it had not occurred to me that Jane Addams might have subdued her own personality for effect. I have long understood her as a shrewd debater, a calm mediator, and a respectful listener, all skills she practiced in order to obtain her reform objectives. I have studied her ability to form coalitions and build networks, which required humility as well as strength. But did Jane Addams regulate her demeanor and her appearance to strike an expected pose for the public?

Yes, I suppose she did. I missed it before, for reasons (or gendered perceptions of my own) I may need to explore later. But now the truth of Jane Addams as a public persona seems clear. The more I have thought about the idea, the more I think I understand the woman behind the persona. It is always rewarding for a historian to pinpoint moments in the lives of their subjects that suggest a shifting perspective, particularly exciting when it reveals a blooming of wisdom. I think it is possible Jane Addams learned the power of appearance in July 1896 when she met Leo Tolstoy. Although the thirty-five-year-old Addams was already a serious woman with seven years of leading Hull-House and a social settlement movement in America to her credit, it was her fashionable 1890s frock that Tolstoy noticed. Addams remembered the meeting in a 1911 article:

Tolstoy, standing by clad in peasant garb, listened gravely, but, glancing distrustfully at the sleeves of my traveling gown, which, unfortunately, at that season were monstrous in size, took hold of an edge and, pulling out one sleeve to an interminable breadth, said that there was enough stuff on one arm to make a frock for a little girl, and asked me directly if I did not find “such a dress a barrier to the people.” — A Visit to Tolstoy, Jan. 1911, JADE.

Jane Addams probably did not return to Hull-House after her trip to Russia and immediately begin constructing a persona more in keeping with her humanitarian work than those voluptuous sleeves. However, Tolstoy’s comments penetrated her psyche. That she told the story fifteen years after the meeting might be enough evidence to prove it. She admired Tolstoy and continued throughout her life to be inspired by his plain-clothes and calloused-hands example of living. Jane Addams was moved at that moment in time of her meeting with an idol to be mindful of the image she portrayed.

At the Jane Addams Papers, we are often frustrated by the quiet, guarded language Addams employed in her correspondence, which makes it hard to know her. Given the care she seems to have always taken with her language, it should not surprise me that by the time Jane Addams became a nationally known figure, a successful reformer and inspirational leader on the public stage, she would understand and make good use of a curated public persona. I had falsely assumed Jane Addams was naturally unassuming instead of shrewdly navigating public expectations about what a female reformer could be and should be and what a credible female reformer must look like. Today, the physical appearance and demeanor of public women is still fraught with gendered assumptions, therefore imagine the dilemma for educated, working women of Jane Addams’s generation. Given the success Jane Addams enjoyed as a reformer, particularly her ability to bridge gaps as wide as the difference between rural clubwomen and American presidents, of course she crafted a persona that paid the proverbial bills.

That there was a Jane Addams persona is not to say that Jane Addams the woman was not a genuine human being. Far from it. Jane Addams was, indeed, motivated by true empathy and real intentions to save the world. That she crafted a public persona simply means that Addams had a private self and a public self, and as a woman the divide between her two selves required special caretaking, especially as success in her line of work required the open hearts and wallets of others. In order to take her compassionate heart and radical ideas out into the world, she had to package that heart and those ideas for public consumption.

So how did the public view Jane Addams? Reformers and scholars and philosophers of her day respected her humanitarian experience, her intellect, and her ideas. Publishers clamored to sell her words and philosophy of reform. Politicians sought her support. Women’s and men’s organizations of all types across the country and around the globe wanted her to speak to their memberships. But how did people see her? What was it about the visage Jane Addams presented to the world that drew people in close enough to hear the important messages she wanted to convey?

After spending some time searching through the documents in the Jane Addams Digital Edition looking for descriptions of Jane Addams’s physical appearance, I was struck not only by the similarity of gendered language to describe her over the years but also by the ways in which those descriptions reflected what the observers themselves defined as appropriate for a woman like Jane Addams in the twentieth century’s first three decades.

Often the descriptions evaluated the womanliness of Jane Addams. As this Washington Herald noted:

These words were spoken in a singularly soft yet vibrantly earnest voice—the voice of a woman dressed in gray, with a face softened by the beauty of tenderness and hair becoming silvered by time. From the face glowed eyes magnetic and prophetic. — We Must Go Man Hunting, Apr. 26, 1908, JADE.

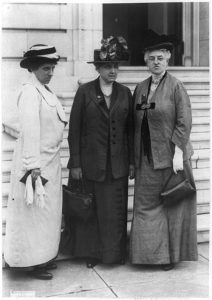

The Birmingham News in 1914 described Addams’s meeting with national suffrage leaders in Alabama as “very human and feminine,” and wrote of Addams:

Simply attired and her graying hair gathered into a loose coil at the back of her neck, this venerable woman was distinctly one of the plain people whom she champions, and the essence of American naturalness. — Speech on Woman Suffrage, Mar. 9, 1914 (The Birmingham News), JADE.

Last night at the Santa Fe railway station, any one observing the passengers who arrived from the west, might have failed entirely to see a motherly looking woman of medium height, with iron gray hair, descending from a Pullman, but once one saw the woman one knew that there was an individual who has been and is, the center of many big things. That person is Miss Jane Addams of Hull House, Chicago. — Speech to the Shawnee County League of Women Voters, Jan. 13, 1922 (Topeka State Journal), JADE.

Jane Addams is gray but she is not masculine nor is she old. Certainly she is not hard. She smiled when the strange thought was told her. “I don’t get enough physical exercise to be hard. No, I’m afraid I’m rather much too soft.” — Interview with Jane Addams, Jan. 30, 1925 (New York Times Magazine), JADE.

Warmth, understanding, keen judgment, shine from her blue eyes; warmth, motherliness, sympathy, strength, mark the face of this American woman who has been a pioneer in social service work and in work for International Peace. The thing which amazes a stranger who meets her is that she, while so many human problems are brought to her, can be so calm, so very calm. — Interview with Jane Addams for the Public Ledger Sunday Magazine, Dec. 1933.

Descriptions of Addams often reduced her, even while praising her:

Miss Addams is not a lecturer, but she is a very interesting talker. While she seemed perfectly at home on the platform her hands were busy all the time toying with her watch and the chain by which it was suspended from her neck. When she spoke she was forceful and energetic but her voice was almost lost in the bigness of the Auditorium. — Speech on Hull-House Work, Dec. 8, 1905 (Topeka Daily Capital, Dec. 9, 1905), JADE.

They offered convoluted or backhanded complements:

A woman so completely wrapped in her work that her other side of life is forgotten, a trifle hardened by the nature of her work, which has brought her in contact with every kind of suffering, are the first impressions gained of Miss Addams, but as talk progresses the softness coming from a big heart creeps into her eyes, about her mouth and a charming elderly woman is revealed. — Interview with Baltimore Evening Sun, Apr. 21, 1922, JADE.

Or they shamelessly judged her physical appearance:

She is a most satisfying person, even in appearance. She has a wonderfully strong face, square as a man’s, and her hair, parted simply and combed back into a low knot, does not conceal a line of the finely modelled head. Her eyes, gray and set wide apart, meet one with an impassive directness even when her straight, firm lips are smiling. Her mouth belongs to a compassionate woman, her eyes to one who is not readily deceived. As for her chin, it is [chiseled] determination. — Interview with Jane Addams, Jan. 30, 1911; (Washington Evening World), JADE.

She is a medium-sized, rather stout, but quick-moving woman. Her manner is brusque but kindly. The blue eyes which have looked upon so much of want and misery, wretchedness and desolation, are sweet in expression and win you to the woman as she talks in her quick, direct manner. Her hair, the style of wearing which she never has changed since she began to coil it up from girlhood’s braids, is parted, and drawn back loosely from a finely shaped forehead. She smiles easily with her eyes, but not with her mouth. Her mouth is grave and rather sad. — Interview with Jane Addams, Sept. 24, 1913 (Pittsburgh Press), JADE.

It is no wonder Jane Addams shunned the camera, relied on a couple of profile pictures for promotional images, and worked so hard to remain in character. No wonder either that observers were so keen to define her and to understand the extraordinary success of this incomparable woman. The St. Louis reporter who wrote this description in 1910, when Addams was serving her historic presidency of the National Conference of Charities and Corrections, leaned toward the poetic:

Miss Addams has a strong personality, that makes itself felt at once through her vital intellectuality and her warm, genial manner. She is of medium stature with bright, luminous penetrating eyes of a blue-gray shade, which are keen and searching. An intense love of mankind pervades Miss Addams’ every word and look. Her prominent cast of features are accentuated by the soft gray with which her hair is just beginning to be sprinkled, and there is a certain nobility and distinction about her carriage which would mark her a central figure in any assemblage, even though her name and fame had not preceded her. It is easy to be led by such a woman, and in the great work to which she has dedicated her life, there is a special field for the qualities with which she is so richly endowed, in the uplifting and betterment of her fellow-beings. — Interview at the National Conference of Charities and Corrections, May 22, 1910 (St. Louis Star & Times), JADE.

In 1928, Jane Addams wrote to an old friend: “I am sending you two pictures, one taken in Rockford in 1881 and one during the first years at Hull-House in 1891. You see I have always worn my hair the same way. A great lack of imagination.”

There was no lack of imagination about it.

Stacy Lynn

Associate Editor

Other Sources: Need a Woman Over Fifty Feel Old?, October 1914; Interview with Donna Risher, Jan. 12, 1920 (Des Moines Tribune); Jane Addams to Margaret Drier Robins, Mar. 6, 1928, all in JADE.

A scholarly editor and historian, Stacy Lynn formerly edited the papers of Abraham Lincoln and currently is an editor at the Jane Addams Papers Project.

During her lifetime, Jane Addams was famous throughout the United States and around the world. Known for Hull-House and as the leader of the American social settlement movement, respected for her wide-ranging reform activities, and beloved for her commitment to economic, political, and social justice for all, Addams became a household name. Reformers, educators, politicians, and the public looked to her for inspiration and for answers to the social and economic problems of the Progressive Era.

During her lifetime, Jane Addams was famous throughout the United States and around the world. Known for Hull-House and as the leader of the American social settlement movement, respected for her wide-ranging reform activities, and beloved for her commitment to economic, political, and social justice for all, Addams became a household name. Reformers, educators, politicians, and the public looked to her for inspiration and for answers to the social and economic problems of the Progressive Era.

Therefore, dear readers who already know the worth of Jane Addams, go forth and spread the Jane Addams word. Watch the documentary, read her books, and tell your friends, family members, teachers, students, and community leaders to do the same.

Therefore, dear readers who already know the worth of Jane Addams, go forth and spread the Jane Addams word. Watch the documentary, read her books, and tell your friends, family members, teachers, students, and community leaders to do the same.