This article in its entirety was published in Volume 46, No. 3 Summer 2022 edition of Chicago Jewish History, a quarterly publication of the Chicago Jewish Historical Society and is being reprinted with the permission of the Society.

A Tale of Many Cultures: Clara Landsberg’s Experiences at Hull House with Eastern European Jewish Immigrants and White Anglo-Saxon Protestant Social Workers

by Cynthia Francis Gensheimer

Clara Landsberg, a Jewish-born teacher, social worker, and pacifist, lived at Hull House in the room directly adjacent to Jane Addams’s for roughly 20 years and made significant contributions to the Chicago settlement house. However, scholars have paid scant attention to her story until now, perhaps because she never sought prominence during her lifetime.[1] While researching her connection with Bryn Mawr College as part of a larger project on early Jewish women students at the Seven Sisters schools, I have discovered that shortly after graduating in 1897, Landsberg left Judaism to become Episcopalian. Afterward, she maintained ties with her influential Jewish parents but also became a member of the nation’s Protestant elite and of an international sisterhood of pacifists. Like many leading women intellectuals and social workers of her day, Landsberg lived with her lifelong partner—a woman—in a predominantly female world. This article will provide an overview of Landsberg’s biography, with a focus on her role at Hull House.

Clara Landsberg, a Jewish-born teacher, social worker, and pacifist, lived at Hull House in the room directly adjacent to Jane Addams’s for roughly 20 years and made significant contributions to the Chicago settlement house. However, scholars have paid scant attention to her story until now, perhaps because she never sought prominence during her lifetime.[1] While researching her connection with Bryn Mawr College as part of a larger project on early Jewish women students at the Seven Sisters schools, I have discovered that shortly after graduating in 1897, Landsberg left Judaism to become Episcopalian. Afterward, she maintained ties with her influential Jewish parents but also became a member of the nation’s Protestant elite and of an international sisterhood of pacifists. Like many leading women intellectuals and social workers of her day, Landsberg lived with her lifelong partner—a woman—in a predominantly female world. This article will provide an overview of Landsberg’s biography, with a focus on her role at Hull House.

Clara was the daughter of a Jewish power couple: Rabbi Max Landsberg and Miriam (Isengarten) Landsberg, leading Jewish intellectuals and nationally known experts on charity administration, with 30 years of hands-on experience in helping the less fortunate in Rochester, New York.[2] Clara’s parents had close working relationships with luminaries Jewish and non-Jewish, including Chicago’s Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch, Hannah Greenebaum Solomon, and Jane Addams.[3] Closer to home, Susan B. Anthony attended the Landsberg congregation’s annual interfaith Thanksgiving services and, in 1892, recommended Miriam Landsberg for a statewide position—although that position was ultimately filled by Anthony herself.[4] The Landsbergs helped lead efforts for social good in Rochester with their closest friends: the Unitarian minister William Gannett and his wife, Mary T. L. Gannett. Clara Landsberg followed her parents’ example in many ways.

Clara can be taken as a case study in the difficulties that many Jewish women of her generation would have faced in attempting to achieve the Landsbergs’ highest ideals. Clara graduated from the most intellectually rigorous women’s college on the East Coast and, through her partner, Margaret Hamilton, became a member of one of the country’s most elite Protestant families. Yet even after graduating from college and becoming Episcopalian, she was denied a job at a girls’ preparatory school because she was still considered Jewish. This discrimination against Jews, even those who had left the faith, was leveled against a young woman of eminent qualifications and impeccable manners. It belied her own parents’ fervent wish that Judaism should be considered only a religion, not a race, and that Jews should find full acceptance in American society.

Born in Rochester in 1873, Clara—and her two younger sisters, Rose and Grace—attended Miss Cruttenden’s School for Girls, which offered a rigorous college preparatory curriculum, but also equipped its students for lives of simple refinement. Although their social world was predominantly Jewish, they had Christian friends as well. At Rose’s confirmation, Rabbi Landsberg enjoined the teenagers coming of age in his Reform congregation to take a rational approach to religion and to determine their beliefs for themselves without feeling bound by tradition.[5] As the Landsberg children would have known, Susan B. Anthony and Mary T. L. Gannett had done exactly that by becoming Unitarians after growing up as Quakers.

At Bryn Mawr College, Clara met her future life partner: Margaret Hamilton, daughter of an upper-class WASP family in Fort Wayne, Indiana.[6] Clara also became acquainted with Margaret’s sisters: Alice Hamilton, who would later establish the field of industrial medicine, and Edith Hamilton, who would famously popularize classical Greek and Roman mythology.[7] Bryn Mawr, founded by Quakers, advertised itself as “pervaded by a simple and practical Christianity” and required daily chapel attendance.[8] Clara, the only Jew of the nearly 50 students in her graduating class, lived on campus and studied classical and modern languages, with a concentration in Latin and Greek.[9] After their 1897 graduation, Clara and Margaret studied abroad at the Sorbonne and the University of Munich.[10]

At Bryn Mawr College, Clara met her future life partner: Margaret Hamilton, daughter of an upper-class WASP family in Fort Wayne, Indiana.[6] Clara also became acquainted with Margaret’s sisters: Alice Hamilton, who would later establish the field of industrial medicine, and Edith Hamilton, who would famously popularize classical Greek and Roman mythology.[7] Bryn Mawr, founded by Quakers, advertised itself as “pervaded by a simple and practical Christianity” and required daily chapel attendance.[8] Clara, the only Jew of the nearly 50 students in her graduating class, lived on campus and studied classical and modern languages, with a concentration in Latin and Greek.[9] After their 1897 graduation, Clara and Margaret studied abroad at the Sorbonne and the University of Munich.[10]

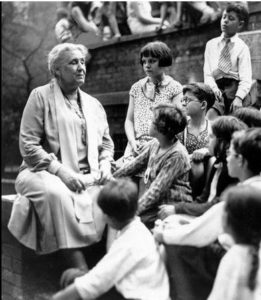

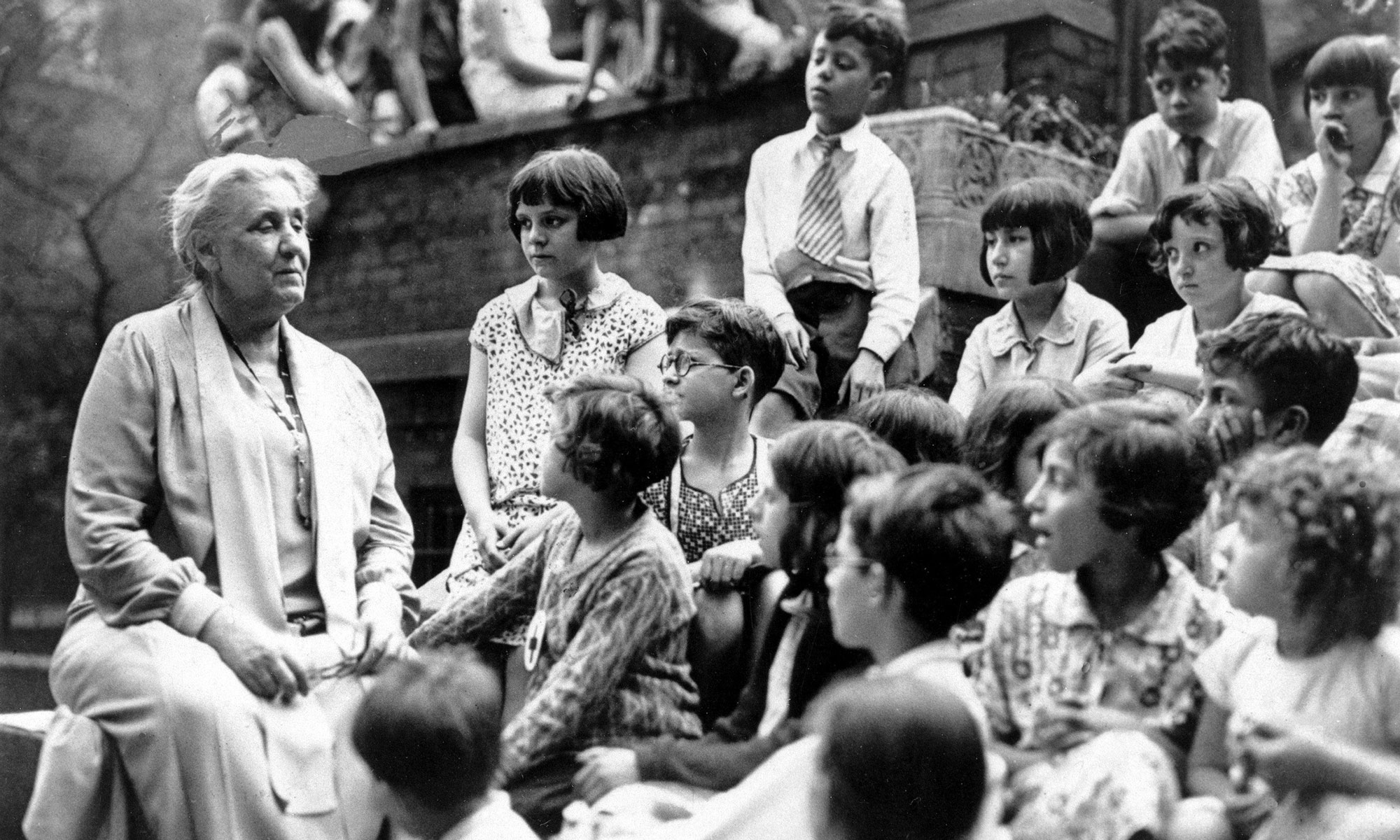

Around 1900, Clara Landsberg moved to Hull House, where she would room with Alice Hamilton for the next two decades.[11] By the time Clara arrived, three-quarters of Hull House’s clientele consisted of Jews from Chicago’s Near West Side and other neighborhoods.[12] These Jews—mostly immigrants from Eastern Europe—came to learn English, attend lectures and concerts, and participate in drama, music, and debate clubs.[13] Despite their apprehensions with respect to Christian proselytizing, they predominated among the 9,000 people who visited Hull House each week.[14] Clara Landsberg earned her living by teaching German and history at a local girls’ school; in her free time, she taught—and later supervised—the evening classes at Hull House.[15]

Jane Addams mentored Clara, who was initially in the unique position of being the only resident who had been born and raised Jewish. Jane Addams called her the “dean of our educational department”—in other words, supervisor of one of the settlement’s core activities.[16] In 1908, a paragraph in the Bryn Mawr Alumnæ Quarterly—likely written by Clara herself—reported that she was living at Hull House to familiarize herself with the problems of immigrants living in “crowded” quarters. Rather than describing her students as Catholic or Jewish, Clara identified them by their various nationalities: “Italian, Greek, Russian, Roumanian, Polish, Armenian, and German.”[17] She explained that they wanted to learn English not only to get good jobs, but also to “study subjects more or less remote from their daily work for much the same reasons that induce people of more fortunate neighborhoods to study Browning, Shakespeare, Ibsen, or Bernard Shaw.”[18] During her early years at Hull House, Clara introduced her students—primarily Eastern European Jews—to some of the classic works of English literature.[19] According to Jane Addams, Clara possessed “an unusual power” as a knowledgeable teacher with an unassuming, quiet presence.[20] In addition, Landsberg had “many friends among the poor people of the neighborhood who are devotedly attached to her.”[21] Two of those friends were Hilda Satt and Morris Levinson.

Hilda Satt’s life was transformed through her long association with the settlement and its residents. Hilda, who had first visited Hull House as a young teenager in 1895, later became a member of one of Clara Landsberg’s reading groups. Certain her mother would disapprove, Hilda had initially declined an Irish friend’s invitation to attend that year’s Hull House Christmas party. In her posthumously published autobiography, Hilda recalled her fear that she would be killed if she attended, because in Poland it had been dangerous for Jewish children to play outside on Christmas. She later wrote, “There were children and parents … from Russia, Poland, Italy, Germany, Ireland, England, and many other lands, but no one seemed to care where they had come from, or what religion they professed … I became a staunch American at this party.”[22]

In one of the first reading groups Clara conducted at Hull House, she ignited a love of English literature in Hilda, who spoke Yiddish at home and had left school after fifth grade to work days sewing shirt cuffs. In addition to the books Clara assigned, Hilda was soon reading “every book I could borrow.”[23] Only a few years earlier, Hilda’s English vocabulary had been so limited that she did not yet know the word “mushroom.” During a meal at Hull House, she had been served a mushroom omelet, of which she would later recall, “I was tortured with the question of whether the mushrooms were kosher.”[24] Soon, however, Hilda counted authors like Dickens and Louisa May Alcott among her friends. Months after meeting Hilda, Clara presented her with a Christmas gift of a copy of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese. Hilda would later recall this as her fondest memory of “Miss Landsberg, … a fragile, ethereal, gentle woman … [who] opened new vistas in reading for me.”[25] With Clara Landsberg’s help, Hilda Satt became an exemplar of the path to Americanization and upward mobility that the settlement aimed to encourage.[26]

In one of the first reading groups Clara conducted at Hull House, she ignited a love of English literature in Hilda, who spoke Yiddish at home and had left school after fifth grade to work days sewing shirt cuffs. In addition to the books Clara assigned, Hilda was soon reading “every book I could borrow.”[23] Only a few years earlier, Hilda’s English vocabulary had been so limited that she did not yet know the word “mushroom.” During a meal at Hull House, she had been served a mushroom omelet, of which she would later recall, “I was tortured with the question of whether the mushrooms were kosher.”[24] Soon, however, Hilda counted authors like Dickens and Louisa May Alcott among her friends. Months after meeting Hilda, Clara presented her with a Christmas gift of a copy of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese. Hilda would later recall this as her fondest memory of “Miss Landsberg, … a fragile, ethereal, gentle woman … [who] opened new vistas in reading for me.”[25] With Clara Landsberg’s help, Hilda Satt became an exemplar of the path to Americanization and upward mobility that the settlement aimed to encourage.[26]

Another of Clara’s students, Morris Levinson, was, like many immigrants, eager to learn English and become an American citizen in the cultural as well as the political sense of the word. With Clara Landsberg as his mentor, he aspired to learn much more than basic skills of vocabulary, grammar, and usage.[27] Landsberg saved two letters that he wrote to her in 1905, while she was home in Rochester convalescing after a serious illness. In broken English, Morris expressed his concern that “Miss Landsberg” was “too sweet, and delicate, to be confind to bed of illness [sic],” reassured her that Ellen Gates Starr had taken him on as a pupil, and told her that he was studying a book she had given him to read: The Boys of 76, a collection of first-hand accounts of soldiers in the American Revolution:

I bolive I should have to know the history of this Country … I have resolved to read it over agan, so that I will remember everything better … Miss Landsberg, I bolive this history will make me a throught citesin.[28]

Morris also confided in Clara. He planned not to live solely seeking fun, “as a great many of people do,” but rather to “try to egicat [him]self as much as poseble” in order to “see the mining of this beautiful world and of the real uman life.”[29] Clara was not only a teacher but a role model for Morris Levinson: someone he admired and to whom he felt a deep sense of gratitude.

Although Hilda, Morris, and Clara had all been raised in Jewish homes, their similarities ended there. Clara’s highly educated, German-born parents spoke fluent English and shunned Yiddish. Like other Reform rabbis, Rabbi Landsberg jettisoned “superstitious forms and antiquated dogmas,” eliminating rituals he considered outmoded, such as Bar Mitzvah.[30] He endorsed the principles adopted by the Reform movement in its Pittsburgh Platform of 1885, but, like Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch of Chicago’s Sinai Congregation, he saw them as only the beginning rather than the end. In 1893, Rabbi Landsberg spoke in Chicago at the World Parliament of Religions, endorsing an expanded role for Jewish women in congregational life.[31]

Clara’s approach to Judaism was virtually the antithesis of that of many of the Jewish immigrants at Hull House. Her father decried Orthodoxy as well as Jewish nationalism. The Jewish immigrants—familiar and comfortable only with Orthodox Judaism—rejected Reform Judaism. Even those atheists, anarchists, and socialists who spurned all religion felt a connection to Yiddishkeit and Jewish peoplehood, concepts rejected by the Landsbergs and most Reform Jews. Did these immigrant Jews nonetheless recognize Clara Landsberg as ethnically Jewish, or did they see her as one of many Protestant residents of Hull House? Might they have accepted her precisely because they had no idea she was Jewish?

Addams and her cohort respected religious differences and tried hard to make Hull House welcoming to all.[32] Yet Jane Addams was motivated by her Protestant faith—especially by the literature and culture of social Christianity, which she described as a “renaissance of the early Christian humanitarianism … with a bent to express in social service and in terms of action the spirit of Christ.”[33] Addams has been criticized for failing to grasp that for many Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Judaism was far more than a religion. On the other hand, features of Hull House that Orthodox Jews would have found off-putting—the Chi-Rho cross Addams always wore, the Christian artwork on display, the lack of kosher food—would not have offended the most liberal Reform Jews such as Clara Landsberg or her mother, Miriam Landsberg.[34]

Miriam Landsberg, Hannah G. Solomon, and other German Jews mirrored mainstream America’s adulation of Addams. One of these Jewish admirers, Sara Hart, called Addams “the single, most influential citizen of my generation.”[35] Miriam Landsberg visited Hull House frequently and helped spearhead efforts among affluent Jews to establish a settlement in Rochester. In 1905, after spending several weeks at Hull House, she wrote: “I do not wonder that any one who has ever lived at Hull House cannot bear to go back to ordinary life.” She described the 21 residents (including her daughter Clara) as a “family” composed of “people of the finest minds” and life at Hull House as “simple, practical, … ideal.”[36]

Miriam Landsberg, Hannah G. Solomon, and other German Jews mirrored mainstream America’s adulation of Addams. One of these Jewish admirers, Sara Hart, called Addams “the single, most influential citizen of my generation.”[35] Miriam Landsberg visited Hull House frequently and helped spearhead efforts among affluent Jews to establish a settlement in Rochester. In 1905, after spending several weeks at Hull House, she wrote: “I do not wonder that any one who has ever lived at Hull House cannot bear to go back to ordinary life.” She described the 21 residents (including her daughter Clara) as a “family” composed of “people of the finest minds” and life at Hull House as “simple, practical, … ideal.”[36]

Settlement work was popular among graduates of Bryn Mawr and similar colleges. Even so, it was not Clara’s first career choice. She and Margaret had wanted to teach at the Bryn Mawr School in Baltimore, but two of the school’s most influential trustees, Mary Garrett and M. Carey Thomas (then president of Bryn Mawr College), refused to hire her because she was Jewish.[37] In 1899, Edith Hamilton (then headmistress of the Bryn Mawr School) wrote to M. Carey Thomas to apprise her of Clara’s conversion:

My sister has just written me that Miss Landsberg is about to become a member of the Episcopal church, and I have wondered whether this would make a difference in your and Miss Thomas’ opinion that we could not offer her a position because she is a Jewess.[38]

Clara Landsberg’s conversion made “not the least difference,” either to Mary Garrett or to M. Carey Thomas, as Garrett explained in her response to Edith Hamilton:

Our objection is one of policy and very few Jews employed in schools or colleges are Jews by religion; it never had occurred to us that Miss Landsberg was really an orthodox Jew. We are wholly unwilling to connect with the school in any capacity a Jew by race, and in view of our feeling of the financial unwisdom of such a step we think that Jews ought to be ruled out of court for the future in consideration of possible appointments.[39]

Yet Clara persisted. In 1900, M. Carey Thomas wrote to Mary Garrett saying, “The Jews enrage me. Is nothing in the world settled? Have Miss Landsberg & the Jews to come up perpetually. It is awfully bad policy.”[40]

Clara remained at Hull House until 1920, when a Quaker organization sponsored her to travel to Vienna to perform postwar humanitarian relief work. Two letters of recommendation finally qualified her as a WASP and (therefore) fit to represent the U.S. abroad. Jane Addams provided a ringing endorsement, and Mary T. L. Gannett was careful to specify: “As a matter of information, Miss Landsberg, during her college course joined the Episcopal Church – and as far as I know is still a loyal member of that Communion.”[41]

When Addams and her partner, Mary Rozet Smith, learned that Clara Landsberg had been accepted to the Quaker program, they both wrote letters of congratulation and farewell. Addams wrote, “I can’t bear to think of H.H. [Hull-House] next winter without either Alice [Hamilton] or yourself.”[42] Mary Rozet Smith wrote: “… no words will express … [our] sense of desolation … when we think of the year without you. … J.A. and I have decided that it is like losing a mother and a child at once. … With Alice in Boston and you in Vienna what will Hull-House be! It is too depressing to face.”[43]

Did Max and Miriam Landsberg know that their daughter was no longer Jewish? In the 1899 letter announcing Clara Landsberg’s conversion, Edith Hamilton had written, “Under the circumstances her family would prefer her not to be at home.”[44] Yet there is no proof that Clara’s parents did learn of her conversion. To all appearances, she maintained a positive relationship with her mother and father throughout their lives. In his final instructions to his children, Max Landsberg wrote, “[M]y life has been one of uniform happiness. The only serious trouble in my whole life has been the loss of my dear wife, your good mother.”[45]

As tolerant as Miriam was toward other beliefs, however, it is likely she would have cared deeply that Clara had left Judaism. At a national conference, as chair of the National Council of Jewish Women’s Committee on Religion, she worried that many German Jews were “given over entirely to materialism and indifference to all Jewish affairs.” She warned Jewish mothers that children raised without religion could “fall prey to … pious sharks … eager for souls.”[46] A few years later, she implored mothers to transmit a love of Judaism to their children “to preserve to our posterity that Judaism which gave Religion to the world.”[47] Despite Miriam’s fears, it is doubtful her daughter would have fallen prey to “pious sharks.” Rather, through exposure to Christianity at school and through her closest friends and role models, Clara rejected the most modern version of Judaism, one carefully crafted by her own parents, in favor of the Episcopal Church, which her father had criticized for what he saw as its strict adherence to ritual and creed.[48]

Part Two of this article will discuss Clara Landsberg’s becoming godmother to Jane Addams’ grandniece, Clara’s travels with Addams, and Clara’s own work as a pacifist, which was deeply informed by her connection with Addams. It will also document her retaining ties to her birth family, even as she joined the Hamilton family as well. And it will describe Landsberg’s trip to Germany with Alice Hamilton just after Hitler had come to power. In a letter to herself documenting the onset of the Holocaust, Landsberg would write, “I am a Jewess.”

Our thanks to Cynthia Francis Gensheimer and the Chicago Jewish History for allowing us to share this article with you.

[1] Even one of Clara Landsberg’s fellow residents, Francis Hackett, seemingly forgot her surname: “Miss Clara, of Bryn Mawr vintage, valiant, tense, souffrante, at once impatient and remorseful, indefatigable and worn-out.” Francis Hackett, “Hull-House: A Souvenir,” 100 Years at Hull-House, eds. Mary Lynn McCree Bryan and Allen F. Davis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1969), 69.

[2] Max Landsberg, born in Berlin in 1845, was a rabbi’s son and a protégé of Abraham Geiger. American Jewish Year Book 1903–1904, 72; http://www.ajcarchives.org/AJC_DATA/Files/1903_1904_3_SpecialArticles.pdf. When Miriam Landsberg, who was born in Hanover in 1847, died, the American Israelite called her death a “loss to American Jewry.” American Israelite, April 25, 1912. Peter Eisenstadt, Affirming the Covenant: A History of Temple B’rith Kodesh, Rochester, New York, 1848–1998 (Rochester: Temple B’rith Kodesh, 1999), ch. 2 and 3; Stuart E. Rosenberg, The Jewish Community in Rochester, 1843–1925 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1954). At a 1910 meeting of the National Conference of Jewish Charities, during Miriam Landsberg’s term as vice-president, Jane Addams gave the opening address, and Rabbi Landsberg served as delegate representing the Jewish Orphan Asylum of Western New York, which he had co-founded and led for decades. Sixth Biennial Session of the National Conference of Jewish Charities in the United States Held in the City of St. Louis, May 17th to 19th, 1910 (Baltimore: Kohn & Pollock, 1910). American Israelite, February 5, 1914, 3. Rabbi Landsberg was elected president of the New York State Conference on Charities and Correction in 1910, when Miriam Landsberg was the outgoing vice-president. “Conference of Charities Holds Three Busy Sessions,” Democrat and Chronicle, November 17, 1910, 17.

[3] As chair of the Committee on Religion of the National Council of Jewish Women, Miriam Landsberg worked closely with Hannah G. Solomon, the organization’s founder. Susan B. Anthony wrote to Miriam Landsberg giving instructions for a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. and letting her know that Hannah G. Solomon and Sadie American had already arrived. Susan B. Anthony to Miriam Landsberg, February 12, 1899, University of Rochester Archives. After Hannah G. Solomon’s daughter, Helen, visited the Landsbergs in 1902, Rabbi Landsberg wrote to Hannah telling her what a “great treat” it had been to have her visit: “Helen reminds me so much of you, although she looks more like the best husband on earth.” He signed the letter, “With love for your husband and all the sisters within your reach.” Max Landsberg to Hannah G. Solomon, April 2, 1902. Helen Solomon Wellesley Correspondence, Hannah G. Solomon Family Collection, MC 749, American Jewish Archives. For the working relationship among Rabbi Hirsch, Hannah G. Solomon, and Jane Addams, see Rina Lunin Schultz, “Striving for Fellowship: Sinai’s Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch and Hull-House’s Jane Addams, A Not-So-Odd Couple,” unpublished manuscript, February 24, 2015.

[4] Ida Husted Harper, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony (Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill, 1898), 2:730. In 1891, Susan B. Anthony, Rabbi Landsberg, and Rev. William C. Gannett spoke at the annual Thanksgiving service. “The Benefits of Unrest,” Democrat and Chronicle, November 27, 1891, 6.

[5] “Rochester, N.Y.,” American Israelite, June 20, 1889, 2.

[6] For background on Bryn Mawr College, see Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women’s Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984) and Horowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994).

[7] For a significant biographical work on the nature of Clara Landsberg’s relationship with Margaret Hamilton, as well as Edith’s connection to Bryn Mawr College and the Bryn Mawr School, see Judith P. Hallett, “Edith Hamilton,” The Classical World 90, nos. 2/3, Six Women Classicists (November 1996–February 1997): 107–147.

[8] Bryn Mawr College Program 1892 (Philadelphia: Sherman & Co., 1892), 77.

[9] Clara Landsberg’s student transcript, Bryn Mawr College Archives. Religious affiliations researched by the author.

[10] Clara Landsberg’s alumna record, Bryn Mawr College Archives. Sandra L. Singer, Adventures Abroad: North American Women at German-speaking Universities, 1868–1915 (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2003), 75, 212.

[11] Presumably by the time that Clara Landsberg moved to Hull-House, she had become a member of the Episcopal church, but evidence surrounding the conversion is scanty, and that surrounding the exact dates of Clara Landsberg’s tenure at Hull-House is contradictory. For Alice Hamilton’s experience at Hull-House, see Alice Hamilton, Exploring the Dangerous Trades (Fairfax, Virginia: American Industrial Hygiene Association, 1995), ch. 4 and 5; Barbara Sicherman, Alice Hamilton: A Life in Letters (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1984), 3–4, 5, 115–136, 139–141, 144–152, 182, 244. Both Hamilton’s and Sicherman’s books are valuable resources that contain references to Clara Landsberg throughout.

[12] Hannah G. Solomon, introducing Jane Addams as a speaker at a national convention of the National Council of Jewish Women. “General Council of Hebrew Women Meets,” The Washington Times, December 3, 1902, 2.

[13] Philip Davis, “Educational Influences,” in The Russian Jew in the United States, ed. Charles S. Bernheimer (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The John C. Winston Co., 1905), 217.

[14] Hull-House was not the only center serving immigrant Jews in its neighborhood. German Jews in Chicago organized their own institutions, and in fact Jane Addams mediated between the German and eastern European Jews when the Jewish-run Maxwell Street settlement was established a few blocks from Hull-House. The first organizational meeting, held at Hull-House in 1892, nearly disbanded due to the terrible arguing between the immigrants and the German Jews who convened the meeting. In an essay titled “A Resented Philanthropy,” one of the immigrants at the meeting later credited Addams with reestablishing civility. He said, “The ‘culture’ which was to emanate from the settlement and permeate all corners of the Ghetto was conspicuously absent from the heated discussion of the ‘enlightened’ benefactors.” In 1907, 150 people visited Hull-House weekly to lecture, teach, or supervise clubs. For Hull-House’s purpose, the names of its residents, and its weekly attendance, see Hull-House Year Book 1907, 5–6 (Archive.org, https://archive.org/details/hullhouseyearboo1906hull/page/38/mode/2up?q=jewish).

[15] Clara’s work evolved over time. She worked full-time at Hull-House for one year, but, finding that too difficult, she eventually taught at the University School for Girls (Miss Haire’s). Alice Hamilton to Agnes Hamilton, [mid-June? 1902], in Sicherman, Alice Hamilton, 142–143. Clara Landsberg’s alumna record, Bryn Mawr College.

[16] Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House (New York: Macmillan, 1912), 437 (A Celebration of Women Writers, ed. Mary Mark Ockerbloom, https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/addams/hullhouse/hullhouse.html).

[17] Italians came to predominate during Clara’s second decade. In 1902, the Chicago Tribune reported on a “Hebrew invasion” in the “crowded west side district”: “As soon as a Jewish family gets a foothold in a tenement other occupants vacate.” “Races Shift Like Sand,” Chicago Tribune, September 26, 1902, 13.

[18] Bryn Mawr Alumnæ Quarterly Vol. 1–2 1907–1909 (Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr Alumnæ Association, 1907–1909) (https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/214021114.pdf).

[19] Francis Hackett wrote in his memoir: “Russian Jews and Jewesses came in great numbers to the classes at Hull House, and had special leanings toward literature” (72). Some English classes were composed entirely of Jews. Philip Davis, “Intellectual Influences,” in The Russian Jew in the United States, ed. Charles S. Bernheimer (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The John C. Winston Co., 1905), 217.

[20] Jane Addams to Anita McCormick Blaine, June 29, 1901, Anita McCormick Blaine Correspondence and Papers, 1828–1958, Wisconsin Historical Society (Jane Addams Papers Project, https://digital.janeaddams.ramapo.edu/items/show/1015).

[21] Jane Addams, American Friends’ Service Committee (AFSC) letter of recommendation for Clara Landsberg, May 1, 1920. AFSC Archives.

[22] Hilda Satt Polacheck, I Came a Stranger: The Story of a Hull-House Girl (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 51–52, 66.

[23] Polacheck, I Came a Stranger, 66.

[24] Polacheck, I Came a Stranger, 66.

[25] Polacheck, I Came a Stranger, 66–67.

[26] In 1905, Hilda Satt took over supervision of the evening classes in Clara’s absence. In 1906–07, she taught beginners’ English at Hull-House. Jane Addams to Clara Landsberg, July 4, 1905, Clara Landsberg Papers, University of Illinois at Chicago Library (Jane Addams Papers Project, https://digital.janeaddams.ramapo.edu/items/show/840); Hull-House Year Book 1906–1907, 8.

[27] Addams noted the frequency with which young Jewish men who had patronized Hull-House also graduated from high school with help from their parents and then managed on their own to go on to college. Twenty Years at Hull-House, 346.

[28] Morris Levinson to Clara Landsberg, May 26, 1905, Additional Papers of the Hamilton Family, 1850–1994, box 13, 83-M175-94-M77, Schlesinger Library. Levinson’s letters are quoted as written, without corrections as to spelling, grammar, or usage.

[29] Morris Levinson to Clara Landsberg, n/d, Additional Papers of the Hamilton Family, 1850–1994, box 13, 83-M175-94-M77, Schlesinger Library.

[30] “Dr. Landsberg’s Closing Lecture,” Jewish Tidings, March 30, 1888, 19.

[31] Max Landsberg, “The Position of Woman Among the Jews,” World Parliament of Religions, Chicago, Illinois, 1893 (GoogleBooks, https://books.google.com/books?id=q2U-AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA241&dq=%22max+landsberg%22+%22The+Position+of+Woman+among+the+Jews%22&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi-3aifgMLPAhUk_4MKHRbLCOIQ6AEIIDAA#v=onepage&q=%22max%20landsberg%22%20%22The%20Position%20of%20Woman%20among%20the%20Jews%22&f=false). When virtually no other rabbi in America would perform an interfaith marriage, both Hirsch and Landsberg did so. Rosenberg, The Jewish Community in Rochester, 93–94. Tobias Brinkmann, Sundays at Sinai (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 136.

[32] In Twenty Years at Hull-House, Addams explained that over time, she and the other residents abandoned Protestant evening prayer, and their demographic composition at least in part reflected the make-up of the neighborhood, including Catholics and Jews, “dissenters and a few agnostics.” Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House, 448–449. Rivka Shpak Lissak has claimed that although many traditional Jews avoided Hull-House, it “had a closer relationship with the marginal Jewish elements, the assimilationists and the radicals.” Lissak, Pluralism and Progressives: Hull House and the New Immigrants, 1890–1919 (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 80.

[33] Rima Lunin Schultz wrote: “For Addams, who affixed a Chi-Rho Cross to her bodice, her work at Hull-House was religious; yet by establishing her settlement as an independent association without ties to any religious organization, university, or other agency, and by not requiring religious worship or religious education, she set out to spread a Christian humanism that she envisioned as cosmopolitan and democratic, inclusive and tolerant. Did this mean that she resolved to exclude religious ideas from Hull-House? I would argue that this has been an area of misunderstanding about Addams’s intentions.” Rina Lunin Schultz, “Jane Addams, Apotheosis of Social Christianity,” Church History 84, no. 1 (March 2015): 207.

[34] Many eastern European Jewish immigrants were strongly attached to Jewish culture and Zionism, even as they lost their connection to Jewish worship. Jane Addams wanted children of immigrants to respect their parents, yet she also saw that many old customs and religious traditions made no sense to the younger generation and in some cases held them back. Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House, 247–248; Rivka Shpak Lissak, Pluralism and Progressives, 80–94. In contrast, on a family trip to Germany when Clara was ten years old, the Landsbergs had appreciated the aesthetic value of medieval Christian architecture such as the Hildesheim cathedral. Clara Landsberg, “Leaves from my Diary,” 1887, 1–4, Additional Papers of the Hamilton Family, 1850–1994, 83-M175-94-M77, box 13, folder 81, Schlesinger Library.

[35] Sara Hart wrote of Jane Addams, “It was my pleasure to know her intimately for more than thirty years.” Sara L. Hart, The Pleasure is Mine: An Autobiography (Chicago, Illinois: Valentine-Newman, 1947), 82. Hannah G. Solomon considered Jane Addams a leader of “all humanity” and “the greatest woman of our century.” Jane Addams inspired Jewish women at the NCJW’s third biennial in 1902, which Solomon attended as president and Miriam Landsberg as vice-president (Hannah G. Solomon, “Council Welfare Work Forty Years Ago and Today,” 4, n/d, Hannah G. Solomon Collection, Library of Congress, box 11, folder 5).

[36] “Sings Praises of Hull House,” Democrat and Chronicle, March 17, 1905, 10.

[37] To understand Mary Elizabeth Garrett and the early history of Bryn Mawr School, see Kathleen Waters Sander, Mary Elizabeth Garrett: Society and Philanthropy in the Gilded Age (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2008).

[38] Edith Hamilton to Mary Garrett, April 18, 1899, Bryn Mawr College Archives, Papers of M. Carey Thomas, reel 214.

[39] I am indebted to Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, who cites this letter and gives a good overview of M. Carey Thomas’s antisemitism in M. Carey Thomas, 230–32, 267, 486. Mary Garrett to Edith Hamilton, April 24, 1899, Bryn Mawr College Archives, Papers of M. Carey Thomas, reel 214.

[40] M. Carey Thomas to Mary Garrett, September 26, 1900, Bryn Mawr College Archives, Papers of M. Carey Thomas, reel 23, nos. 37–39.

[41] Mary T. L. Gannett, letter of recommendation, May 4, 1920, Clara Landsberg’s personnel file, AFSC Archives.

[42] Jane Addams to Clara Landsberg, August 7, 1920, Hamilton Family Collection, 84-M210, box 1, folder 7, Schlesinger Library. Alice Hamilton had just been appointed the first woman professor at Harvard’s School of Medicine.

[43] Mary Rozet Smith to Clara Landsberg, August 7, 1920, Hamilton Family Collection, 84-M210, box 1, folder 7, Schlesinger Library.

[44] Edith Hamilton to Mary Garrett, April 18, 1899.

[45] Max Landsberg to his children, January 16, 1918, Max Landsberg SC 6602, American Jewish Archives.

[46] “The Council’s Report on ‘Religion,’ ” The Reform Advocate, March 24, 1900, 167 (The National Library of Israel, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/?a=d&d=refadv19000324-01.1.11&e=——-en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxTI-%22miriam+landsberg%22————-1).

[47] Miriam Landsberg, “Report of Committee on Religion,” The Reform Advocate, January 3, 1903, 452 (The National Library of Israel, https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/refadv/1903/01/03/01/article/29/?srpos=12&e=——190-en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxTI-landsberg+committee+on+religion————-1).

[48] Max Landsberg criticized Episcopalians for requiring members to “believe in the forty-nine articles of faith” and Presbyterians for the Westminster catechism. “What is Judaism?” Democrat and Chronicle, November 22, 1899, 11. The Hamilton sisters, whose family Clara Landsberg joined, had been reared in the Presbyterian congregation founded by their grandfather, but, as children, they preferred the small Episcopal church on Mackinac Island, where they spent their summers. For a thorough discussion of the Hamilton sisters’ religious upbringing, see The Education of Alice Hamilton, eds. Matthew C. Ringenberg, William C. Ringenberg, and Joseph D. Brain (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), esp. 13–14, 23–24. For a discussion of religion among the residents of Hull-House, see Eleanor J. Stebner, The Women of Hull House: A Study in Spirituality, Vocation, and Friendship (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997).

Cathy Moran Hajo is the Editor and Director of the Jane Addams Papers Project at Ramapo College of New Jersey. She is an experienced scholarly editor, having previously worked for over 25 years as Associate Editor at the Margaret Sanger Papers at New York University. Dr. Hajo received her Ph.D. in history from New York University in 2006, and is addition to her work on the Sanger Papers, published “Birth Control on Main Street, Organizing Clinics in the United States, 1916-1940,” in 2010.

Her teaching interests include scholarly editing and digital history, and she currently teaches for the Institute for Editing Historical Documents, the Digital Humanities Summer Institute. She teaches a digital history course at Ramapo College.

Clara Landsberg, a Jewish-born teacher, social worker, and pacifist, lived at Hull House in the room directly adjacent to Jane Addams’s for roughly 20 years and made significant contributions to the Chicago settlement house. However, scholars have paid scant attention to her story until now, perhaps because she never sought prominence during her lifetime.

Clara Landsberg, a Jewish-born teacher, social worker, and pacifist, lived at Hull House in the room directly adjacent to Jane Addams’s for roughly 20 years and made significant contributions to the Chicago settlement house. However, scholars have paid scant attention to her story until now, perhaps because she never sought prominence during her lifetime. At Bryn Mawr College, Clara met her future life partner: Margaret Hamilton, daughter of an upper-class WASP family in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

At Bryn Mawr College, Clara met her future life partner: Margaret Hamilton, daughter of an upper-class WASP family in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In one of the first reading groups Clara conducted at Hull House, she ignited a love of English literature in Hilda, who spoke Yiddish at home and had left school after fifth grade to work days sewing shirt cuffs. In addition to the books Clara assigned, Hilda was soon reading “every book I could borrow.”

In one of the first reading groups Clara conducted at Hull House, she ignited a love of English literature in Hilda, who spoke Yiddish at home and had left school after fifth grade to work days sewing shirt cuffs. In addition to the books Clara assigned, Hilda was soon reading “every book I could borrow.” Miriam Landsberg, Hannah G. Solomon, and other German Jews mirrored mainstream America’s adulation of Addams. One of these Jewish admirers, Sara Hart, called Addams “the single, most influential citizen of my generation.”

Miriam Landsberg, Hannah G. Solomon, and other German Jews mirrored mainstream America’s adulation of Addams. One of these Jewish admirers, Sara Hart, called Addams “the single, most influential citizen of my generation.”

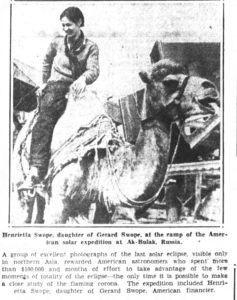

So she left Chicago to take a job at Harvard to work for the astronomy professor Dr. Harlow Shapley at the Harvard Observatory. While she looked for variable stars and became Shapley’s first assistant, she earned a Master’s degree in astronomy from Radcliffe College in 1928. The following year, she became famous when she identified 385 new stars, which helped scientists identify the “hub” of the Milky Way. At the time, Swope was touted as “one of the youngest women ever to have made a comparable mark in scientific research.” During her long, successful career as an astronomer, she studied Cepheid variable stars in dwarf galaxies and M 31, the Andromeda Galaxy. However, her most significant contribution was developing a new method for measuring the universe, using the brightness of stars, which became known as the “celestial yardstick.” I don’t understand any of this, but it sounds amazing. Henrietta Swope was an accomplished and well-respected scientist.

So she left Chicago to take a job at Harvard to work for the astronomy professor Dr. Harlow Shapley at the Harvard Observatory. While she looked for variable stars and became Shapley’s first assistant, she earned a Master’s degree in astronomy from Radcliffe College in 1928. The following year, she became famous when she identified 385 new stars, which helped scientists identify the “hub” of the Milky Way. At the time, Swope was touted as “one of the youngest women ever to have made a comparable mark in scientific research.” During her long, successful career as an astronomer, she studied Cepheid variable stars in dwarf galaxies and M 31, the Andromeda Galaxy. However, her most significant contribution was developing a new method for measuring the universe, using the brightness of stars, which became known as the “celestial yardstick.” I don’t understand any of this, but it sounds amazing. Henrietta Swope was an accomplished and well-respected scientist.