Since the Middle Ages, female servants referred to as maids have been serving Masters of prestigious wealth and status. In the past, maidens, who were young, unmarried women, had to dedicate service to their Masters for life and did not marry; these women did not expect wages as long as they received food, clothing, and a home to sleep in. As the working and living conditions of house maids have evolved, these domestic workers now have families of their own to serve. Women needed to earn enough to put food on the table or pay that month’s rent. Forming a lasting union where housekeepers can advocate for good pay, fair hours, and reasonable employers was often a figment of the imagination in the past and even now. House maids are still victims of long work hours with underpay.

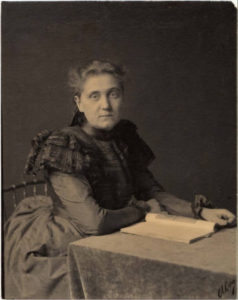

Ellen Martin Henrotin, an active social reformer, tried to unite servant girls in 1901, believing that a union would provide better conditions for not only maids but also their employers as well. Jane Addams supported this movement and agreed that maids should come to know each other through organization. In fact, Addams advocated that maids should have another home to return to at night where they could be surrounded by friends. She told this story,

“I have just received a letter from a clever young woman I know, telling me that she wanted to attend a university this fall and get a Ph. D. She would be glad to do housework as a means to the Ph. D. end, but she could not live with the family by whom she would be employed.”

However, the lack of strategy in organizing these domestic workers is why maids have not yet earned a national union today. Each maid’s needs and working conditions are diverse, and it’s difficult for them to band together for a specific, common goal. Housekeeping does not have a formal hiring process because job opportunities come by word-of-mouth, and wages are set verbally.

Mexico saw progress when The National Union of Domestic Workers applied for recognition in 2015. The group targeted assistance toward victims of discrimination and violence in their employer’s homes. Yet, exclusion of groups from unions does not bring justice to everyone and leaves women angry.

When Sophie Becker organized the Working Women’s Association of North America in 1901, scrub women and laundresses were angry for not being asked to join. They cried, “I am just as good as you are.”

While maids have yet to band together for a national union, it is still important for women to fight for fair working conditions. As Jane Addams wrote,

“The number is increasing of those optimists in this country who are prone to say that everything is right and will come out right in the end. But we who are working for the improvement of the condition of wage-earners, are inclined to think that the conditions of women need improvement and that their condition will be bettered only as we concentrate intelligent thought upon the subject and are active toward that end.”

Sources: Jennings, Karla. “The History of Maids.” Hankering for History, 12 Aug. 2013, http://hankeringforhistory.com/the-history-of-maids/. Accessed 22 Aug. 2017; “In Trouble Already.” The Topeka Daily Capital, 25 Aug. 1901, p. 11; “Union as Aid to Maid.” The Inter Ocean, 23 Aug. 1901, p. 2; “Women Will Organize Women Wage Earners.” Oakland Tribune, March 27, 1905, p. 7.