Chicago, Il. is home to “Helping Hands,” the city’s first monument devoted to Jane Addams and those whom she helped. Addams fought for equality and is best known as the founder of Hull-House and the mother of the social work movement. She was also a passionate advocate for the rights of immigrants, the poor, and women, and a founder of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. It’s safe to say that Jane Addams deserves recognition for her humanitarian and legendary work. Continue reading “Jane Addams’ “Helping Hands””

Women and the Nobel Peace Prize

Jane Addams was the first American woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts in the peace movement and social work, but who were the other women who have won the prize? Learn a little bit about each of the 16 total women winners and when they won their prizes. Continue reading “Women and the Nobel Peace Prize”

The 1915 Trojan Women Tour

1915 was a momentous year for women’s efforts for peace and suffrage. Jane Addams and others established the Women’s Peace Party (WPP), met at the International Congress for Women, formed the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace (ICWPP), (known today as the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom [WILPF]), and held a massive Suffrage parade in New York City, N.Y. While they worked together for one ultimate goal — equality — they used a variety of methods, one of which was revisiting Ancient Greece.

Continue reading “The 1915 Trojan Women Tour”

“From Hull-House to Herland”: Lorraine Krall McCrary’s Guest Blog Post

I had the pleasure of asking Lorraine Krall McCrary about her new article “From Hull-House to Herland: Engaged and Extended Care in Jane Addams and Charlotte Perkins Gilman,” (Politics & Gender, August 2018, 1-21). She examines the writings and activities of Jane Addams and Charlotte Perkins Gliman and how the two activists’ opinions on the roles women have in politics, society, and family differed. Continue reading ““From Hull-House to Herland”: Lorraine Krall McCrary’s Guest Blog Post”

Give Peace a Chance: Some Ideas Sent to Jane Addams

If you were given three wishes, what would they be? One of the most common answers is world peace. It’s only natural that people want peace, especially with the barrage of headlines screaming about war and conflict. Continue reading “Give Peace a Chance: Some Ideas Sent to Jane Addams”

“Trolls” Have Been Around For Years

People blame the Internet for what seems like the spread of anger, meanness and bad manners. While the internet makes it easier to reach more people with much more speed, the things that people share is not so terribly different. Internet trolls, hecklers, and flame warriors seem to be modern phenomena, but it is the method, not the content that is modern. Continue reading ““Trolls” Have Been Around For Years”

A Guest Blog Post by Taylor Mills on The New Women of Chicago’s World’s Fairs (1893-1934)

I was fortunate enough to get in contact with Taylor Mills, current curator at the Chisholm Trail Museum and recent graduate of the University of Central Oklahoma, who wrote her MA thesis on the women of the Chicago’s World’s Fairs from 1893-1934. She spoke of her interest in the topic, what her research focuses on, and her thesis process. Continue reading “A Guest Blog Post by Taylor Mills on The New Women of Chicago’s World’s Fairs (1893-1934)”

The Tragic Case of Baby Bollinger

A little over 100 years ago, the case of an infant allowed to die in a Chicago hospital captured the nation’s attention. Born on November 12, 1915, “Baby Bollinger” died five days later on November 17, after physician Harry Haiselden refused to operate to save his life. Haiselden made his decision because the child was born with deformities and he believed the the boy was was mentally and morally defective. He convinced the child’s mother, who said “the doctor told me it would be, perhaps, an imbecile, a criminal. Left to itself it has no chance to live. I consented to let nature take its course.” (Boston Globe, Nov. 17, 1915, p. 1.) Haiselden’s controversial decision led to a heated debate in newspapers across the country. Continue reading “The Tragic Case of Baby Bollinger”

Addams’ Living Legacy in Color

The inspirational legacy and work Jane Addams left behind is no secret; from Hull House to social reform to woman’s suffrage, Addams’ was a revolutionary thinker for her time and a true inspiration for so many people, including artist George Giusti (1908-1990) who was inspired to take Addams’ vision of equality and bring it to life in one of his best regarded pieces of art.

Jane Addams was an advocate for social justice including inclusivity regardless of skin color. Addams’ wanted to give every person and equal opportunity shown through her lifelong effort to fight for social reform and offer all an equal opportunity for a better life in Hull House. After her passing, her work was still unfinished but she gave hope and opened the door for true equality for all.

Flash forward 20 years after Addams’ death, Italian-born artist, George Giusti, created his Civilization is a method of living, an attitude of equal respect for all men.”–Jane Addams, Speech, Honolulu, 1933. From the series Great Ideas of Western Man in 1955. Giusti wanted to avoid classical art and focus on a more modern and relevant effect, which shows through many of his pieces. Giusti’s works did not relate to the time period he created them in, giving them a futuristic effect that modern society still relates to.

So why did Giusti pick Addams’ quote for the title? Well, Addams was a known advocate for equality regardless of race. The drawing that Giusti created illustrates a sense of community, unity and equality, all goals to which Addams had dedicated her life. Her goals were not realized in her lifetime and by the 1950s were still plaguing American society. Racial tension in American society divided the nation, and Giusti was inspired to visualize Addams’ quote as a call for equality.

Despite years of advocating and pushing for change, social reform is still an issue in today’s society. Giusti’s drawing received numerous awards and recognition, while Addams’ work has lead her to be one of the most historical and influential figures of the 20th century. Her unfinished business still inspires thousands to this day, with no sign of slowing down.

Civilization is a method of living, an attitude of equal respect for all men.”–Jane Addams, Speech, Honolulu, 1933. From the series Great Ideas of Western Man. (Smithsonian American Art Museum.)

“George Giusti,” ADC Hall of Fame, 1979.

Addams’ Rhetoric on Home, City, and World: A Guest Blog Post by Dr. Liane Malinowski

Dr. Liane Malinowski is a Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Marist College. Her research explores Hull House residents’ rhetoric as it relates to their planning of domestic and urban spaces. This post derives from her recently-completed dissertation titled Civic Domesticity: Rhetoric, Women, and Space at Hull House, 1889-1910. Find her on Twitter @lianemalinowski.

My recent research on Addams and her Hull House colleagues focuses on how they reimagined urban space through visual, verbal, and material means. I was particularly interested in how women at Hull House claimed the authority to speak and write about urban space to local and national audiences, especially in the late-nineteenth century when women were not conferred the status of citizen, and rhetorical convention discouraged women from speaking in public.

I was motivated to take up this project in part because I think of Addams as an important but understudied speaker, writer, and theorist of concepts important to rhetorical studies, such as democracy, ethics, and memory. After surveying published and archival sources, I found that Addams and colleagues were prolific producers of experimental and hybrid texts that drew from parlor rhetoric traditions, domestic literature, social science genres, and city planning discourses. The Jane Addams Papers Project was a wonderful resource for studying documents related to Addams, Hull House, other residents, and the interconnected web of social welfare organizations in Chicago and beyond.

Regarding Hull House residents’ rhetorics of urban space, I argue Addams, along with Ellen Gates Starr, Julia Lathrop, Florence Kelley and others represented city spaces at a variety of scales as cosmopolitan, or nationally-diverse. These spaces included their West Side neighborhood and Hull House itself. An obvious example of this kind of representation is Florence Kelley’s “Nationalities Map,” in the collaboratively-written Hull House Maps and Papers, in which she visually locates families of varying national backgrounds in Hull House’s neighborhood.

Not only did residents represent urban space as cosmopolitan in documents, they also curated cosmopolitan spaces for rhetorical purposes. For example, upon founding Hull House, Addams and Starr curated it to reflect a cosmopolitan aesthetic through its artwork and artisan-made furniture and wares. They were motivated to do this in order to establish common ground with their immigrant neighbors with whom they believed they shared an interest in European art, music, and literature.[1]

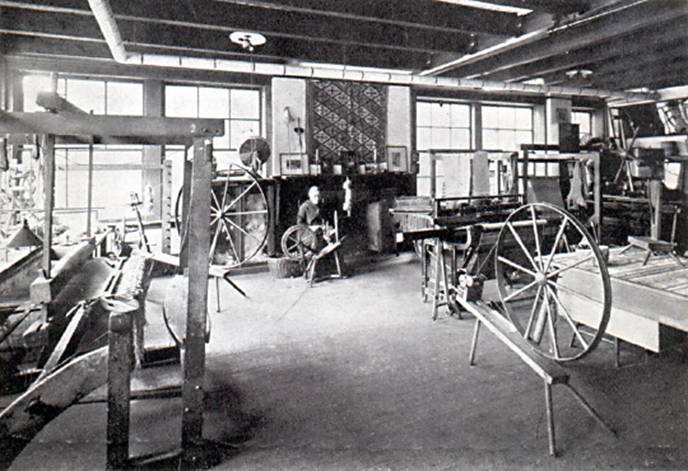

Residents who represented spaces as cosmopolitan, however, did so with troubling political implications because they often spoke about and for their immigrant neighbors, and in so doing, flattened the specificity of their neighbors’ national identity in favor of emphasizing diversity. As part of this problematic history of claiming authority over cosmopolitan geographies, residents often extended their representations of urban space to include nationally-diverse people as objects of display. For example, in the early 20th century, Hull House residents curated a Labor Museum that displayed local immigrants performing artisan labor such as spinning textiles and weaving baskets. Residents also disseminated texts about the museum, such as the First Report of the Labor Museum in 1902. In this report, Addams argued that the Labor Museum presented an evolutionary narrative of work to audiences, and showed manual, pre-industrial labor as preceding industrial labor. She hoped younger people in the neighborhood would learn to appreciate their parents’ and grandparents’ artisan skills that were rendered obsolete by the industrial economy in Chicago. At the same time the museum performed this teaching function, I argue it also objectified immigrant artisans and their cultural artifacts by reinscribing older, neighborhood artisans as outside the contemporary moment by placing them and their labor prior to present industrial conditions. And, while Addams constructed herself as an authority over the entire museum and its message in the First Report of the Labor Museum, neighborhood women were figured as objects of display through photographs, captioned to suggest they are representatives of different kinds of foreign womanhood (the captions read “Italian Woman,” “Syrian Woman,” and “Irish Woman,” for example). Through the museum itself, and also texts such as the First Report, Addams and other residents participated in a trend of American women asserting their privilege to claim knowledge over foreign places and people as a way to join in public discourse about civic space and identity.[2]

After researching Hull House residents’ representations of cosmopolitan spaces in the 1890s and 1900s, I appreciate there is still much to explore about Addams’ rhetoric, especially surrounding her theorizing of how culture and class identities play a role in enabling and constraining communication. Based on my research experiences, I would encourage others undertaking study of Addams’ rhetoric to look across the JAPP Microfilm Edition, the JAPP Digital Edition, and traditional archives dedicated to Addams and Hull House in libraries. Each of these resources is organized in different ways, which can help researchers make new connections between documents. For example, some of the traditional, library archives file documents organized by author name, whereas the JAPP Microfilm Edition is largely filed by the kind of text produced at Hull House (letters, meeting minutes, financial records, etc), and the JAPP Digital Edition gets even more specific because it tags documents by key terms. Triangulating my search for documents across these resources was incredibly generative for my reading of Addams’ rhetoric.

[1] To gain a sense of Hull House’s cosmopolitan aesthetic, see Nora Marks’s “Two Women’s Work: The Misses Addams and Starr Astonish the West Siders,” Chicago Tribune. 19 May 1890, or the photographs included in Hull House Maps and Papers.1895. Urbana: UI Press, 2007.

[2] Kristin Hoganson’s Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865-1920. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2007, helped me understand the broader contours of American women’s claims to cosmopolitan geographies.