On May 12, 1902, Jane Addams was aboard the California Limited, traveling on the Santa Fe Railroad line on her way home to Chicago. She had been in Los Angeles for a national convention of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. The California Limited, inaugurated in 1892, was billed as the “finest train west of Chicago.” It featured Pullman sleeping cars, an observation deck, and dining cars, and it offered “the highest attainment in luxurious railway travel.”

Jane Addams was a seasoned traveler, had toured Europe twice, traveled to Paris for the World’s Fair in 1900, and had visited much of the United States. Yet she was often an impatient traveler, and long journeys tended to steal her energy. She accepted train travel as a regular occurrence in her busy life, but riding on trains and waiting on trains sometimes made her tired and cranky. She had been anxious about the long trip to the West Coast and, in fact, might have begged off if she had not promised Florence Kelley she would go. Kelley was a committee chairwoman for the Federation and headed up the panel on which Addams was presenting a paper. Addams went West not for herself, but at the behest of her friend. She wanted to support her old Hull-House colleague, but she had been “quite dreading California.”

train travel as a regular occurrence in her busy life, but riding on trains and waiting on trains sometimes made her tired and cranky. She had been anxious about the long trip to the West Coast and, in fact, might have begged off if she had not promised Florence Kelley she would go. Kelley was a committee chairwoman for the Federation and headed up the panel on which Addams was presenting a paper. Addams went West not for herself, but at the behest of her friend. She wanted to support her old Hull-House colleague, but she had been “quite dreading California.”

To her surprise, however, the journey out to California turned out to be a delightful and welcomed reprieve. It was “very easy,” she wrote Mary Smith, “Mrs Wilmarth, Mrs Ward and I had a state room together and read aloud and united our souls to no end.” Mary Wilmarth and Lydia Coonley-Ward, both active members of the Chicago Women’s Club, were also attending the national convention.

Addams’s time in California was also something of a triumph for her public reputation. At the convention, which was a great success and drew enthusiastic attention, Addams delivered a well-received speech, “The Social Waste of Child Labor.” She also earned praise for the “intense” appeal she made on behalf of African-American women’s clubs, when the Federation, to placate the white southern women in attendance at the convention, effectively voted to bar black clubs from admission to the national organization. Addams also made public appearances and delivered speeches beyond the convention, spending two weeks as a media darling. A reporter who covered her speech at a Y.M.C.A. in Los Angeles, for example, marveled at her “extremely effective presence” and the frequent applause Addams’s speech there garnered. And an early historian of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs noted in her 1912 history that “no woman at the Los Angeles Biennial could have failed to be greatly impressed by the address of Jane Addams of Illinois.”

Addams’s time in California was also something of a triumph for her public reputation. At the convention, which was a great success and drew enthusiastic attention, Addams delivered a well-received speech, “The Social Waste of Child Labor.” She also earned praise for the “intense” appeal she made on behalf of African-American women’s clubs, when the Federation, to placate the white southern women in attendance at the convention, effectively voted to bar black clubs from admission to the national organization. Addams also made public appearances and delivered speeches beyond the convention, spending two weeks as a media darling. A reporter who covered her speech at a Y.M.C.A. in Los Angeles, for example, marveled at her “extremely effective presence” and the frequent applause Addams’s speech there garnered. And an early historian of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs noted in her 1912 history that “no woman at the Los Angeles Biennial could have failed to be greatly impressed by the address of Jane Addams of Illinois.”

Still, Jane Addams of Illinois was underwhelmed by the convention. As she wrote Smith, “I met with all the delegates as wise as an owl as to looks, but it all seems terribly remote and save for the color question without any real issue.” Although she was a supporter of women’s clubs, she was not, in her bones, a club woman. As well, she was anxious to get back to work in Chicago, was longing for home, and itching to return to Hull-House, having spent much of the spring on the road.

At 6 p.m. Saturday, May 10, she boarded the California Limited at the Los Angeles train station to embark on the approximately fifty-seven hour journey to Chicago. A successful trip in the books, Addams settled in for the ride, tucked up with a good book and good company. A “very  easy” journey home? Not so much.

easy” journey home? Not so much.

Just before 10 o’clock on the following Monday morning, her train was nearing Revere, MO, a few miles northwest of Keokuk, IA, and still nearly 300 miles southwest of Chicago. Addams was sitting in her section of the train with her nephew James Weber Linn, a University of Chicago professor, who was traveling with her. Suddenly, an axel on the dining car broke, the train ran into a switch and crashed into a box car sitting on a side track. A corner of the dining car was torn off and six of the train’s cars derailed. Addams was “thrown with quite a degree of violence to the side of the coach.”

In the first decade of the twentieth century, train accidents were on the rise. Americans at this time were ninety times more like to die in a train wreck than they were to die in an airplane crash a century later. On the California Limited that day, one man was killed and many passengers were injured. A physician on board attended to Addams, who injured her arm and torso and suffered lacerations on her face from a shower of broken glass from the car’s shattered windows. In a public statement later that day, Addams told reporters: “The same jolt that injured me threw my nephew to his feet, saving him from serious hurts. I was thinking of something else at the time and didn’t have time to make any effort to save myself. The crash came without warning.”

Addams was pretty banged up in the accident, arriving home to Chicago later that night to a group of worried Hull-House residents, who collected her at the train station. She would take a few days to rest and recover, and would experience some lingering aches for the rest of the month. Yet she was sanguine when she wrote Mary Smith a week after the accident.

Dearest: I have had my R.R. wreck at last, the pain, the moment of panic, the thrill, the rescue, all very neatly enacted. The ten days thereafter, [although] containing some very miserable hours, have not on the whole been so bad & I find this morning — the first downstairs — filled with a content so deep that it reminds me of that of the early days of H. H. You have been a saint about writing, three of your letters during the first week and cheered me to the soul.”

Jane Addams was not one to dwell on her difficulties and always as quick to return to her work as possible. Following the train wreck, she cleared her calendar, striking one particularly busy day entirely off, but soon her schedule was full again. On May 26, she hosted friends for a Hull-House play, addressed the Merchants’ Club of Chicago on May 31, and was back on a train in July for a long trip to upstate New York.

Jane Addams was a woman who filled up nearly all her days with her reform activities and her writing. Women in perpetual motion, ever engaged in good work, have no time for a derailment. Not by trains, nor by anything else.

By Stacy Lynn, Associate Editor

Notes: Mark Aldrich, “Public Relations and Technology: The ‘Standard Railroad of the World’ and the Crisis in Railroad Safety, 1897-1917,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, 74 (Winter 2007): 76-77; Michael Bezilla and Luther Gette, Branch Line Empires: The Pennsylvania and the New York Central Railroads (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 219-20; Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Haste, eds., Women Building Chicago: A Biographical Dictionary (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 183-85, 982-86; Steve Glischinski, Santa Fe Railway (Minneapolis: MBI Publishing, 2008), 35, 139; Mary I. Wood, The History of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (New York: General Federation of Women’s Clubs, 1912), 141-45; “To Chicago and New York; The California Limited—Daily,” Advertisement, The Los Angeles Times, Feb. 27, 1901, p. 1; “Colored Clubs Need Not Apply,” The Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1902, p. 44; “California Limited,” Advertisement, San Bernadino (CA) County Sun, May 11, 1902, p. 4; “Santa Fe Train Is wrecked Again,” Salt Lake (City) Telegram, May 12, 1902, p. 6; “Santa Fe Limited in Wreck,” The St. Louis Republic, May 13, 1902, p. 3; “Miss Addams Hurt in Wreck,” The Inter Ocean (Chicago), May 13, 1902, p. 1 (clipping); “Jane Addams Injured,” The Daily Times (Davenport, IA), May 14, 1902, p. 10; “Jane Addams Still Suffers,” The Los Angeles Times, May 14, 1902, p. 2; “The Federation’s Best Brilliancy,” The Los Angeles Times, May 4, 1902 (drawing); “Colored Clubs Need Not Apply,” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1902, p. 44; Jane Addams Diary, Mar. 15-May 8, May 24, July 4, 1902, Jane Addams Papers Microfilm, 29:796-810, 813, 822; Jane Addams to Mary Rozet Smith, April 8, 1902; Jane Addams to Mary Rozet Smith, April 16, 1902; Jane Addams to Mary Rozet Smith, May 3, 1902; Statement on Train Wreck, May 12, 1902; Jane Addams to Mary Rozet Smith, May 19, 1902; Jane Addams to Mary Rozet Smith, May 26, 1902; Delinquent Children, May 31, 1902; Jane Addams to Mary Rozet Smith, August 5, 1904, all in Jane Addams Digital Edition.

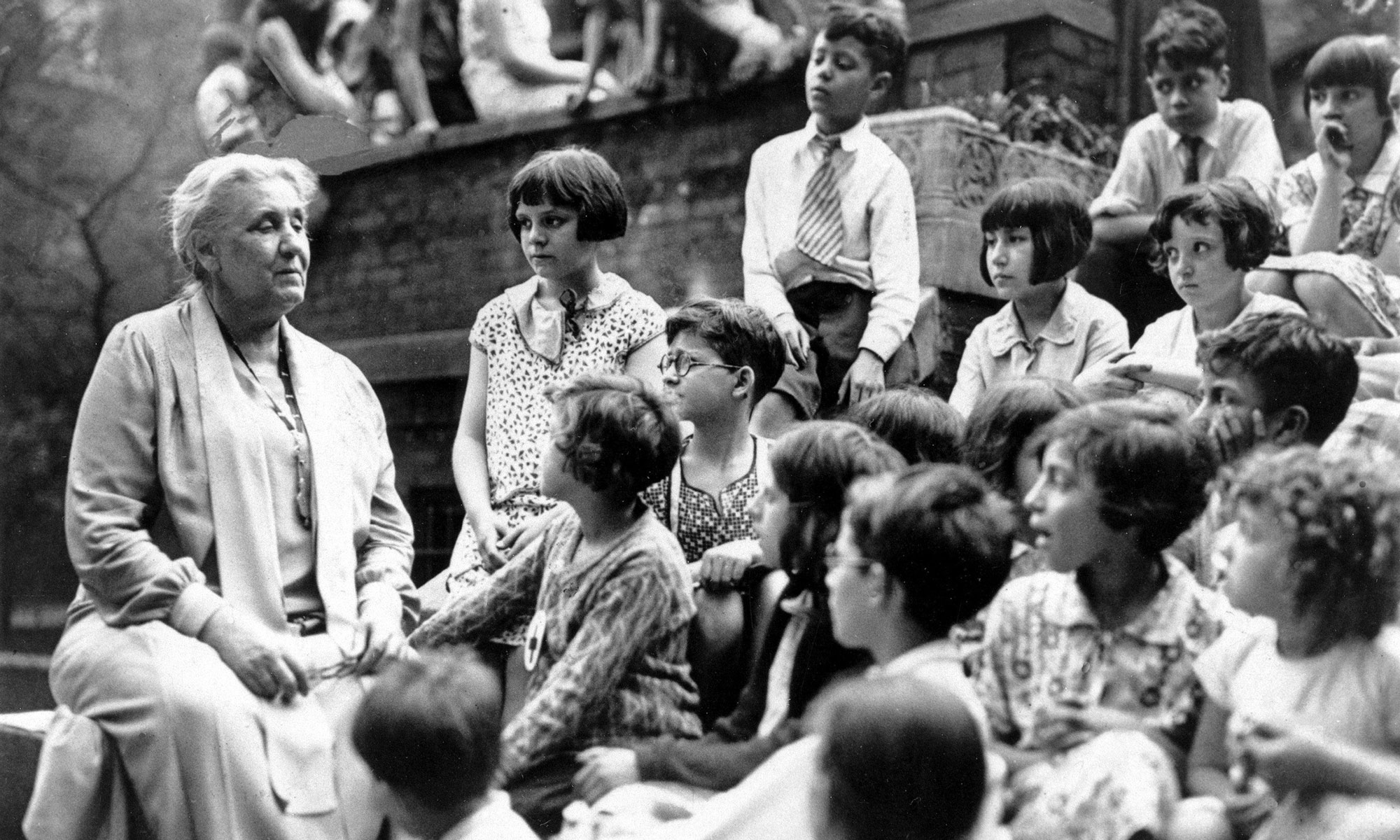

Photographs: Jane Addams, c. 1900; All Aboard the California Limited, c. 1905; both photos courtesy of Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

A scholarly editor and historian, Stacy Lynn formerly edited the papers of Abraham Lincoln and currently is an editor at the Jane Addams Papers Project.