I am an impatient woman, which makes me feel particularly indebted to patient women like Jane Addams who struggled year after year after year to convince men to give them the right to vote. I salute those women and whisper to their spirits that I am grateful for their patience and that it is lucky good they didn’t have to count on me. I would have wanted to bonk upside their heads those men in power who looked on, made fun, and kept saying “NO!” That the suffragists stayed the persistent course in the face of persistent rejection in order to gain a right so obvious (yes, even back then it was obvious) is heroic to me. I would have found it quite impossible to maintain for decades the energy it took to keep advocating, educating, marching, lobbying, writing, and coming up with new arguments and new nonviolent activities to bring awareness to the injustice of men denying women the right to vote, only to fail in that effort over and over and over again.

Suffragists were superheroes. They are my superheroes.

However, I must admit that it is a challenge sometimes to study the woman suffrage movement knowing how many freaking years it was going to take to be successful. It is hard to see some of the suffrage activities through the long and winding history of the movement as anything other than futile. But, thankfully, there are some suffrage efforts so inspired, so bursting with wisdom and enthusiasm that I wish I could have been there fighting with those goddesses of persistence.

Take the 1909 suffrage train from Chicago to Springfield as one shining example.

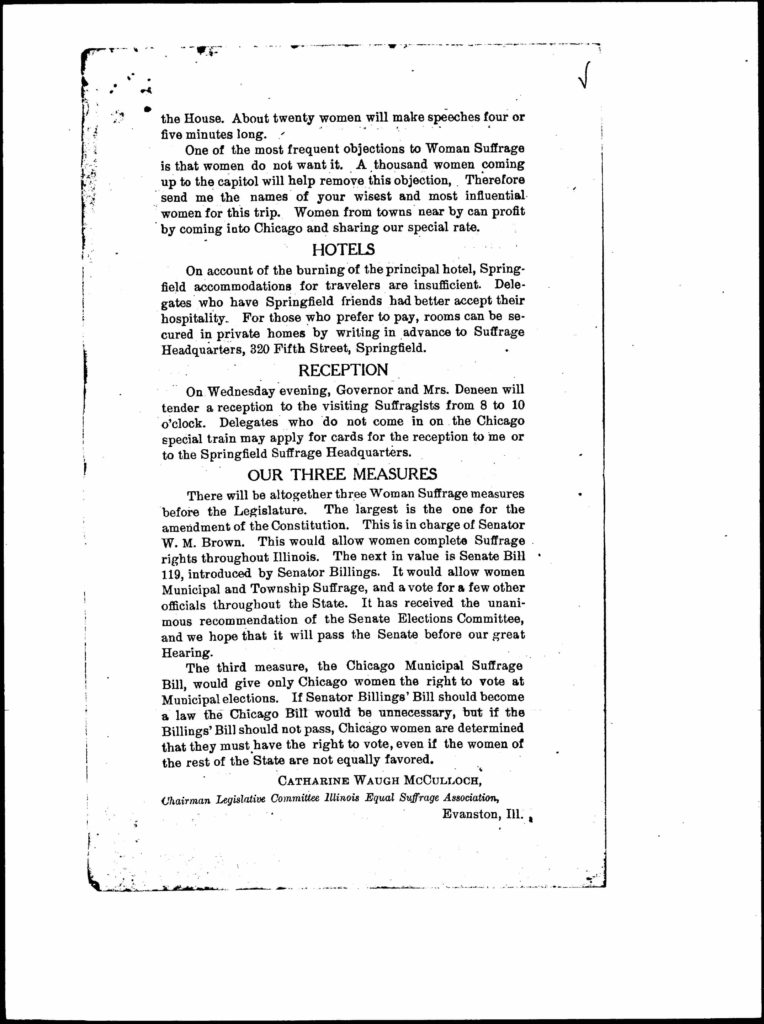

In the spring of 1909, there were three suffrage bills bouncing around like playground balls in the Illinois State Capitol, because there were a few suffrage supporters among the men in the Illinois General Assembly (Senators William M. Brown and Charles L. Billings, along with Rep. James M. Kittleman, all of Cook County, for example, each introduced suffrage bills). One such measure was a long-shot constitutional amendment to grant universal suffrage to Illinois women. There was also a Senate bill to allow Illinois women to vote in city and state elections, which had little-to-no support in the House. And there was the Chicago Municipal Suffrage Bill to give women in Chicago the right to vote in city elections. Illinois suffragists understood that the constitutional measure was on par with “when pigs fly,” but they were hopeful for the third measure and praying for the second, which would render the third measure moot.

Enter Superhero Catharine Waugh McCulloch.

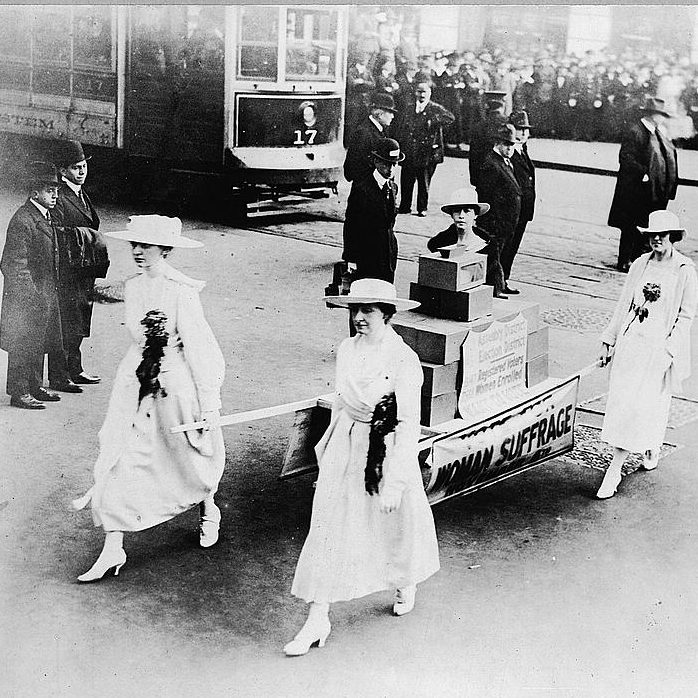

McCulloch, a lawyer and justice of the peace in Evanston, Illinois, was chairman of the Legislative Committee of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association. In order to raise public awareness of the suffrage bills and hit members of the Illinois legislature with reasoned arguments, coming at them from every angle imaginable, she spearheaded a star-studded, public spectacle, suffrage extravaganza. The event was to start in Chicago with a special suffrage train filled with the “wisest and most influential women” in Illinois, continue with whistle-stop suffrage speeches in six cities on the way to Springfield, and culminate in a public hearing of joint committees of the Illinois Senate and House of Representatives at the State Capitol Building. It would be the biggest, boldest lobbying effort of the Illinois suffrage movement to date, a giant push to collect new converts to the cause.

Superhero Jane Addams was one of the other women leading the charge.

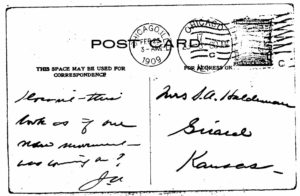

Addams was a member of the municipal suffrage committee in Chicago. In January the committee set up headquarters in the Stratford Hotel and “began the work of canvassing the entire city for the right to vote.” They held Saturday morning meetings and covered the city with posters. In February, Addams sent a suffrage postcard to her sister, writing: “Doesn’t this look as if our new movement was coming on?” The suffragists in Illinois were turning up the heat, as Addams declared in March: “There are plenty of things we need in this country for the protection of the health and the morals of our people. We could have them if we would ask for them, but the men won’t ask for them, and the women cannot.”

The women would, therefore, descend upon Springfield to make the case. On Tuesday, April 13, the special train, costing $5.50 for the round-trip fare and with a reported 150 suffragists on board, left Chicago on the Chicago & Alton Railroad at 10:30 in the morning. The train arrived at the first whistle stop in Joliet an hour later. Leading a group of four women who addressed a crowd at the Alton Depot of several hundred from a platform at the rear of the train, Jane Addams said:

“For many years the women have gone to Springfield, and in fact to all the capitals in the United States, asking for the right of voting. Their enfranchisement is no longer considered a radical move. The adherents of the move have steadily grown in numbers until today the movement has assumed an important position throughout the world. The women of today are treated in many ways the same as men. They have equal responsibilities and should be enfranchised. In Finland, which is a part of Russia, there are women in the parliament. It is hard to believe that America would be behind such a country in a matter so important. Belgium, England, and English colonies are giving more and more rights to women, and Illinois should not be in the rear. We ask reasonably for your sympathy in this movement. You have representatives in the legislature. Those men are anxious to please their constituents. A delegation of women is not going to have much weight with them, but your wishes will. We ask you to use what influence you have for our cause. It is but a reasonable request.”

A reasonable request, indeed.

After the rousing stop at Joliet, the suffrage train continued on, stopping in Pontiac, Lexington, Bloomington, Atlanta, and Lincoln. Greeted by large crowds at each depot, the women took turns on the rear platform making their case for the vote. The Joliet News called them the “Conquering Heroines.”

At the hearing the next day, Senator Kittleman gave the chair and gavel to Jane Addams, who introduced each of the nineteen suffrage speakers, all women except for one. Each of the speakers made their unique arguments in favor of woman suffrage grounded in their own particular experiences. The sheer magnitude of this brilliant lobbying effort was inspiring. By way of celebrating all the superheroes who took part I offer the full roster of speakers and the titles of their speeches:

- “Increasing Evidence that Women Want the Ballot,” Ella Stewart (1871-1945), President of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association, married to Oliver Stewart, a former member of the Illinois legislature

- “Changing Public Opinion toward Municipal Suffrage,” Elia W. Peattie (1862-1935), Chicago Tribune literary editor

- “The Indirect Benefits of the Ballot,” Anna Nicholes (1865-1917), settlement worker and clubwoman

- “The Ethics of Equal Suffrage,” Prof. Herbert L. Willett (1864-1944), University of Chicago Professor of languages and literature

- “The Lack of the Ballot the Handicap of the Working Girl,” Agnes Nestor (1880-1948), a trade union organizer representing the International Glove Worker’s Association

- “The Need of the Ballot for Working Women,” Margaret Dreier Robins (1868-1945), President of the Chicago branch of the Women’s Trade Union League

- “The Woman Official and the Ballot,” Catharine Waugh McCulloch (1862-1945)

- “The Farmer’s Wife and the Ballot,” Norah Burt Dunlap (1856-1932) a clubwoman from Savoy, Illinois

- “The Professional Woman and the Ballot,” Marjorie Gomery of Rockford, Illinois

- “The Foreign Woman and the Ballot,” Lilian Anderson, (b. c. 1883), a librarian at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois

Julia Lathrop, Jane Addams, and Mary McDowell in Washington, D.C., lobbying for woman suffrage, 1913 - “The College Associations for Equal Suffrage,” Harriet Grimm (b. c. 1886), who earned her Ph.D. at the University of Chicago in 1908

- “Church Interests and Suffrage for Women,” Eugenia Bacon (1853-1933), a clubwoman from Decatur, Illinois

- “The Ballot for Women and Progressive Legislation,” Mary McDowell (1854-1936), director of the University of Chicago Settlement

- “The Experiences of the Chicago Municipal Suffrage Campaign,” Mrs. William Hill

- “Improved Sanitary Legislation and the Ballot,” Dr. Caroline Hedger (1868-1951), a Chicago physician

- “The Justice of Equal Suffrage,” Rev. Kate Hughes (b. 1854), minister of a church in Table Grove, Illinois, and former president of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association

- “The Attitude of the Illinois Club Woman toward Equal Suffrage,” Elizabeth Hawley Everett (1857-1940), President of Illinois Federation of Women’s Clubs, Highland Park, Illinois

- “Modern Philanthropy and the Ballot for Women,” Flora Witkowsky (1869-1944), President of Jewish Chicago Women’s Aid

- “The Ballot for Woman and Legal Protection of Children,” Harriet Park Thomas (1865-1935), Secretary of the Juvenile Protective Association of Chicago

None of the measures about which the speakers hoped to inspire legislative action that day passed into law. However, the suffragists won some allies and shifted momentum in their favor. They showed up and they proved they were in it to win it. They were determined to persevere, and just because I know it would take another four years until Illinois women would win voting rights does not render that suffrage train and hearing futile. The superhero suffragists did not get what they wanted in April 1909, but they made some serious noise and changed the game. The suffrage train of 1909 and the hearing orchestrated by the dynamic Catharine Waugh McCulloch and conducted by the cool and collected manner of Jane Addams was the dramatic beginning of the final push.

Nineteen cheers for these nineteen superheroes. And a hundred cheers for their persistence.

The legislative suffrage campaign in Illinois had begun in 1891 with a failed vote on a constitutional amendment to grant woman suffrage, continuing with more failed bills in 1893, 1895, 1897, 1901, 1903, 1905, 1907, and 1909. Finally in 1913, the Illinois legislature voted on S.B. 63 to grant women aged 21 and older full presidential and municipal suffrage and partial state and county suffrage. The vote in the Senate was 29 to 15 in favor of passage. In the House, the successful vote was 83 to 58. The suffragists had never wilted in the face of rejection. They were persistent. They kept on asking for the vote. And on June 26, 1913, when the bill became law, Catharine Waugh, Jane Addams, and all the other suffrage heroes finally got the answer they deserved.

Sources: Steven M. Buechler, The Transformation of the Woman Suffrage Movement: The Case of Illinois, 1850-1920 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1986), 174-82; Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast, eds., Women Building Chicago (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 560-65, 623-26, 634-36, 846-49; Martha G. Stapler, ed., Woman Suffrage Year Book (New York: National Woman Suffrage Association, 1917), 16, 29; 46th Illinois General Assembly, listed in John Clayton, comp., The Illinois Fact Book and Historical Almanac, 1673-1968 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1970), 265-67; Laws of the State of Illinois (1913). 333; “An Act to confer the right to vote at municipal elections upon women citizens of the city of Chicago,” Mar. 23, 1909; Journal of the House of Representatives of the 46th General Assembly of the State of Illinois (Springfield: State Printers, 1909), 324; “An Act granting women the right to vote at certain elections,” Jan. 11, 1910, Journals of the Senate and House of Representatives, Special Session of the 46th General Assembly (Springfield: State Printers, 1910), 86, 218; “Petticoat Diplomacy,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 17, 1908, p. 7; “Chicago Suffragettes to Stop in Joliet Thirty Minutes,” The Joliet Evening Herald-News, Apr. 8, 1909, p. 3; “Crowds Gather at Stations,” Chicago Tribune, Apr. 14, 1909, p. 3; “Critic Fires Hot Blast at Suffragists,” The (Chicago) Inter Ocean, Apr. 14, 1909, p. 1, 3; “The Conquering Heroines Came,” The Joliet News, Apr. 15, 1909, p. 3; Illinois Equal Suffrage Association Flyer, c. April 1909, Jane Addams Papers Microfilm Edition, 41:1082; and from the Jane Addams Digital Edition (JADE): Jane Addams to Sarah Alice Addams Haldeman, Feb. 23, 1909; Jane Addams Says that American Women are Slower, March 19, 1909; Woman Suffrage Is Needed in Chicago, March 24, 1909; Jane Addams to Agnes Nestor, April 9, 1909; Jane Addams to Agnes Nestor, April 9, 1909; Address to Women’s Suffrage Rally at Joliet, Illinois, April 13, 1909.

Images: Elizabeth Hawley Everett in Illinois Club Bulletin 1 (Oct. 1909): 2; Lathrop/Addams/McDowell, Nestor, Ella Stewart, and NYC parade, all from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs; Suffrage Train from The (Chicago) Inter Ocean, Apr. 14, 1909, p. 3: Postcard, JADE.

A scholarly editor and historian, Stacy Lynn formerly edited the papers of Abraham Lincoln and currently is an editor at the Jane Addams Papers Project.

When we were approached by the Long 19th Amendment team, we were excited to participate for two reasons. Jane Addams isn’t known primarily for her work for woman suffrage. She is often mentioned in lists, or gets a small part in the larger history, but in her day, Addams was a leading suffragist. She was a vice president of the National Woman Suffrage Association and used her considerable fame to promote the movement. She gave frequent speeches on woman suffrage, especially on its

When we were approached by the Long 19th Amendment team, we were excited to participate for two reasons. Jane Addams isn’t known primarily for her work for woman suffrage. She is often mentioned in lists, or gets a small part in the larger history, but in her day, Addams was a leading suffragist. She was a vice president of the National Woman Suffrage Association and used her considerable fame to promote the movement. She gave frequent speeches on woman suffrage, especially on its