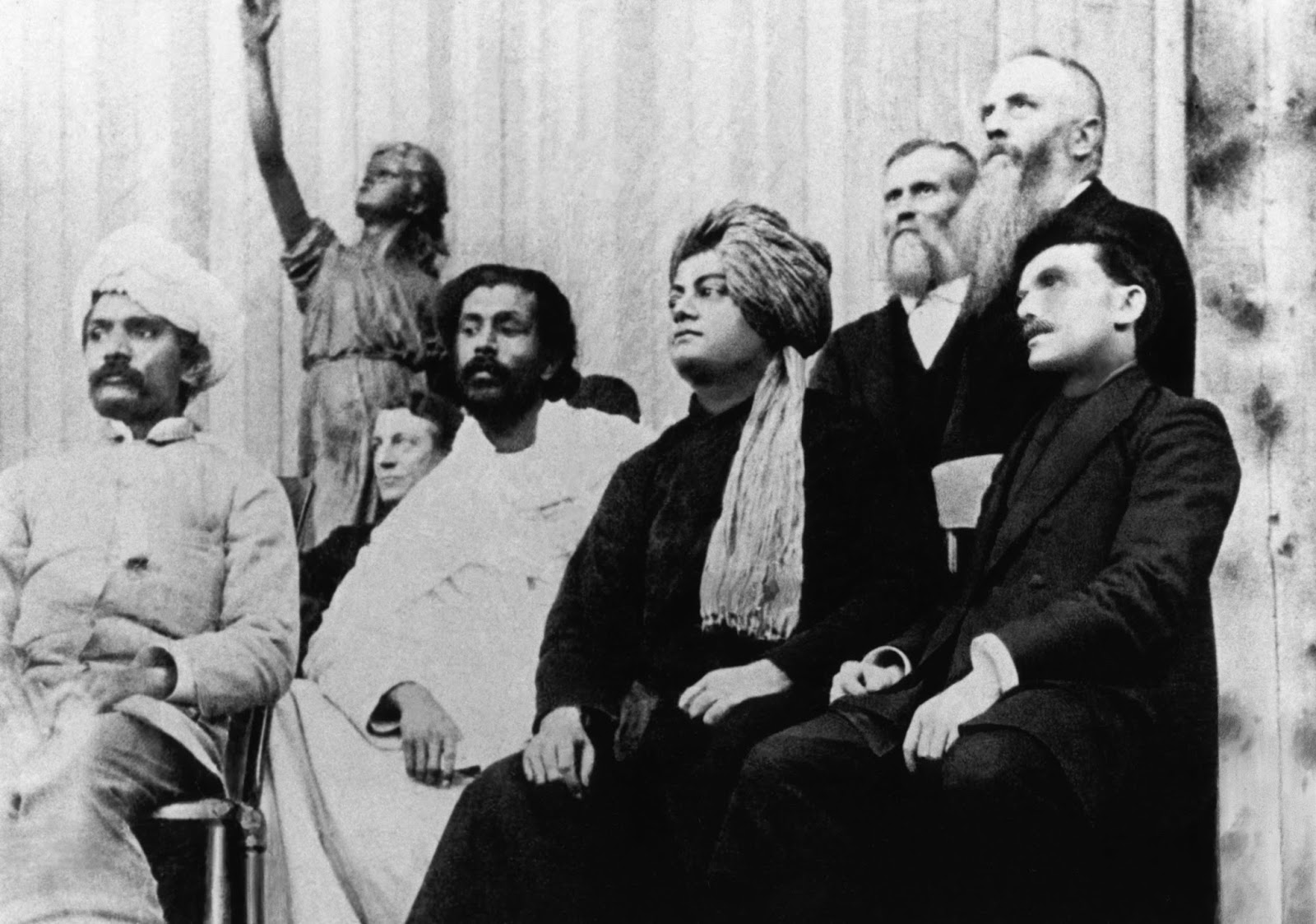

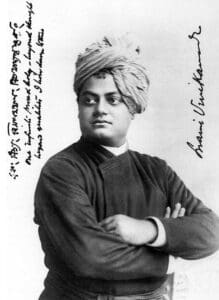

It was my first weekend of an intensive 200-hour yoga training course. I was sitting with my yogi cohorts on my mat after an energetic yoga flow. We were listening to our first yoga humanities lecture on the history of yoga. Yeah! History is always the very best place to start when exploring any new topic or activity. I was enthusiastically taking notes on the history handout, listening to tales of ancient and modern practices of yoga, when—bam!—there was Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu munk from India, coming to Chicago in 1893 to participate in the Parliament of Religions held at the World’s Columbian Exposition. On this visit to the United States, Vivekananda introduced the practice of yoga and “made a big and lasting impression on the American public,” wrote Georg Feuerstein, yoga scholar and author of “A Short History of Yoga.”

Jane Addams was in Chicago in 1893. She attended that Chicago World’s Fair. She was curious about everything, always learning, always open to new philosophies and practices, always eager to bring fascinating people to Hull-House. I bet she met Swami Vivekananda, I thought.

At the first opportunity, I searched for Vivekananda in the Jane Addams Digital Edition. And there he was! He was tagged to a speech Jane Addams delivered in November 1933 in which she said:

“I am reminded of a story told to me forty years ago by Vivekananda, a great Hindu teacher who went about in India expounding what he thought to be the great meaning and the purpose of life.” Forty years ago was 1893.Yep, Jane Addams knew Swami Vivekananda. Of course, she did. After a little more digging, I also found that Addams had related this same Vivekananda story in a 1911 speech about selflessness and charitable work, and I was able to then identify the “native of of East India” she referenced as Vivekananda himself. In this research, I also located three new Jane Addams letters to add to our digital edition.

In Addams’s 1933 speech, given during the terrible throes of the Great Depression, she recounted Vivekananda’s allegorical tale in detail:

“He told about a woman who found herself at the bottom of a pit. I suppose every religion has some sort of pit in it which it brings out on occasion. This woman was at the bottom of the pit, very hot and very uncomfortable. Because she felt so uncomfortable and so unhappy she sent up prayer after prayer to the throne above, begging that she might be released from this punishment. Finally word came down to her that if she could think of one unselfish thing she had ever done it would be taken into consideration and perhaps she would be taken out.

“She thought and thought, trying to remember an unselfish act. Finally she remembered that one day when she was sitting in her doorway getting some carrots ready for dinner a blind beggar came by and asked her for something to eat and that she had given him a bad carrot that she was not going to use herself anyway. It was not a very unselfish act, but the best that she could recall.

“Then she waited. After a while there came down into the pit from above a carrot attached to a string. It came lower and lower. She was told to take hold of this carrot and that perhaps it would pull her up. So she took hold with great fear and trembling. It began to go up and went up farther and farther and the atmosphere grew more salubrious and she felt very much happier. Then she looked back and found that somebody was clinging to her feet and coming with her, and somebody else was clinging to his feet and somebody clinging to the feet of that man. There was a whole string of people coming out of the pit upon this one carrot. She knew that it would not last very long. She knew that it was not a good carrot; so she called out ‘Let go, this is my carrot, my one chance to get out of this place.’ Then, of course, the carrot immediately broke and they all went down together.

“Vivekananda contended that if we were not thoroughly concerned about our neighbor’s good, if we were not given to considering their good quite as valuable and important as our own, then we were not on the right path of going up. When we begin to say, ‘This is mine and mine alone,’ then we are sure to drop back.”

Born Narendranath Datta into an upper-middle-class family in Calcutta in 1863, Vivekananda studied at Presidency College before becoming a disciple of the Hindu mystic Ramakrishna (spiritual guru and founder of the Ramakrishna Order) in 1881. He studied and toured throughout India before coming to the United States in 1893. In lectures and various public and private appearances, Vivekananda shared the Vendanta philosophy based on four sacred Vedic texts. In his lectures he discussed those texts, like the Bhagavad Gita (a first century epic Sanskrit poem), the divinities of Hinduism (Vishnu, Shiva, and various goddesses), and yoga. It is unclear when Addams heard the story of the woman and the carrot, but there were multiple opportunities for her to hear Vivekananda speak. He was in Chicago from September 1893 through June 1894, delivering multiple speeches at various venues. He also visited Hull-House at least once during this time, delivering a lecture on the economic and social conditions in India on October 24, 1893. After his Hull-House lecture, at which Addams was likely present, Vivekananda entertained questions for an hour, overseeing a lively discussion.

Addams may have also attended a Vivekananda lecture in New York City in December 1895; and Vivekananda was back in Chicago for appearances in April 1896. During that latter trip, he wrote to a friend: “Everything has been well arranged here, thanks to the kindness of Miss Addams. She is so, so good and kind.”

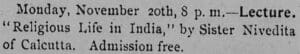

Vivekananda returned to Chicago in late November 1899 and visited with Addams at Hull-House. Before his arrival in Chicago his disciple, Sister Nivedita of the Order of Ramakrishna (born Margaret Elizabeth Noble in Ireland), lodged at Hull-House for several days. She described the settlement ethos as “perfect self-forgetfulness—all generosity and enthusiasm.” In a letter from Chicago, she wrote: “At Hull House I feel myself in a more natural atmosphere than elsewhere. … There—one is in the world. The whole interest is life and ideas.”

After Sister Nivedita delivered a lecture at Hull-House on November 20, she wrote: “Last night at Hull House I really did feel that we had had Swami’s blessing…60 or 70 people stayed about 1½ hour to ask questions about the philosophy. And such intelligent questions too!” Sister Nivedita was impressed with the settlement and inspired by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr (“I love her so much,” she later wrote of Starr). Sister Nivedita gave at least two more lectures at Hull-House, including one to the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society entitled “The Ancient Arts of India.”

Sister Nivedita dedicated her life to the study of Hinduism and to the education of girls in India. She also nursed patients in Calcutta during a bubonic plague epidemic in 1899, and later joined Gandhi’s movement to liberate India from British rule. Sister Nivedita described Jane Addams as “a clear-headed quiet and unassuming person,” and she was so impressed with Addams’s compassion and reform work to better the lives of vulnerable people, she called Addams a karma yogi.

Today, we think of yoga mostly as a practice of movement, meditation, and breath work. However, there is also a deep cultural and spiritual practice associated with yoga that emphases compassion for self and others, moral restraints (yama) such as nonviolence and truthfulness, and observances (niyama) such as study and contentment. The practice of karma yoga has some uncanny philosophical similarities with the Progressive Reformers. Selfless service. A desire to perform one’s duty without attachments to personal gain. Motivation of a social gospel for collective uplift. Commitment to justice and nonviolence. The idea that all people are worthy of dignity and respect, akin to possessing, in the language of yoga, Atman, or the true nature within all beings.

Karma is the universal law of cause and effect. Karma yoga is “the practice of serving others while seeking to relinquish the ego judgments projected by one’s own ego.” A karma yogi gives freely of herself and is self-controlled, sincere, truthful, loving, and filled with the desire to serve.

That philosophy sounds just like Jane Addams to me.

Jane Addams dedicated her life to improving the lives of vulnerable people—children, immigrants, women, and the working poor. She cared deeply about people she knew in the Hull-House neighborhood and in Chicago as well as the people she didn’t know in Illinois, in the United States, and throughout the world. She gave all her money and energy to the causes she served. Jane Addams was not driven by ego, and she lived a life of compassion and nonjudgment. She always sought to understand people on their own terms, to respect their beliefs and cultural traditions, to study the social and economic conditions that affected their health and wellbeing, and to tell the truth about the social ills she witnessed. She used her talents as an organizer, a philosopher, a public speaker, and a writer for the good of society not for personal wealth or accolades.

Addams wrote in 1910: “If at times the moral fire seems to be dying out of the good old words, relief and charity, it has undoubtedly filled with a new warmth certain words which belong distinctively to our own times; such words as prevention, amelioration and social justice. It is also true that those for whom these words contain most of hope and warmth are those who have been long mindful of the old tasks and obligations as if the great basic emotion of human compassion had more than held its own. After all, sympathetic knowledge is the only way of approach to any human problem.”

Philanthropic endeavor to Jane Addams was more than an occupation, it was a higher calling. She would not have defined what she was doing as karma yoga, but she was emulating the very heart of its philosophy.

Here is a humble sampling of Jane Addams Yoga Sutras (sutra = thread; general truth; rule or aphorism):

“No man, whatever his genius or his organizing ability, can hope to permanently uplift himself or his followers, unless with them he uplift the masses.”— How Would You Uplift the Masses?, February 4, 1892

“Too often we make our attitude toward the poor one of duty rather of sympathy and love. This must be changed if success would attend our efforts.”— Social Settlements, August 12, 1900

“The gravest charge I have to bring against Child labor is that it pauperizes the consumers, all of those who use the product into which this labor has entered. If I wear a garment which has been made in a sweatshop or a garment for which the maker has not been paid a living wage, or a wage so small that his earnings had to be supplemented by the earnings of his wife and children, then I am in debt to the man who made my cloak. I am a pauper if I permit myself to accept charity from the poorest people in the community.”—Child Labor and Pauperism, October 3, 1903

“The fittest man in a community is not the man who crushes his rival in business, who survives all his rivals, but the man with the greatest and broadest sympathies. The desire to crush out others, whether commercially or physically, is a sure sign of arrested development. As we go on to a deeper understanding of the philosophy of life we avoid combat more and more.”—Newer Ideals of Peace, February 19, 1904

“We must search in the dim borderland between compassion and morality for the beginnings of that cosmopolitan affection.”—Newer Ideals of Peace, 1907

“Man excited is quite different from man when calm. When we are angry we talk of what we can do; when our anger has passed away we consider what we should do.” Is the Peace Movement a Failure, November 1914

Stacy Lynn

Associate Editor

Notes: Darren Main, Yoga and the Path of the Urban Mystic, 2nd ed. (iUniverse Star, 2007), 57-62, 73, 76-94, 224; “Vivekananda” (1863-1902), Nivedita (1867-1911), and Ramakrisna (1836-1886), Encyclopedia Britannica; John Henry Barrows, The World’s Parliament of Religions, 2 vols. (R. R. Donnelley, 1893), 1:66, 5, 101-2 (speech), 118-20 (fable), 124, 128-29, 148, 153, 170-71; 2:968-78, 1590; “Chronology of Vivekananda” (https://chronologyofvivekananda.rkmm.org/k); “Sister Nivedita’s Battle for Indian Ideals in America,” Daily Katha blog, June 24, 2018; Vivekananda to Sarah Chapman Bull, April 6, 1896, in Advaita Ashrama, ed., Letters of Swami Vivekananda (Modern Art Press, 1940), 306; Letters of Swami Vivekananda, 111; Swami Vivekananda, Yoga Philosophy: Lectures Delivered in New York, Winter of 1895-96 (Longmans, Green & Co., 1896); Sankari Prasad Basu, ed., 2 vols., Letters of Sister Nivedita (Nababharat Publishers, 1960), 1:229, 230, 241, 248-51; The [Chicago] Inter Ocean, Dec. 2, 1899, p. 13; and from the Jane Addams Digital Edition (the first three are newly located): Margaret Noble (Sister Nivedita) to Jane Addams, Feb. 14, 1906; B. M. Malabari to Jane Addams, May 26, 1906; Jane Addams to Sara Chapman Bull (Mrs. Ole Bull), June 23, 1906; Charity and Social Justice, June 11, 1910; Address at the Indiana State Conference of Charities and Correction, October 29, 1911; November 1914; Pioneering in Social Work, November 1933.