For the twenty years I edited Abraham Lincoln’s papers, I never had a strong desire to own a Lincoln document. Well, let’s be honest, I never made enough money to buy a Lincoln document. Even a clipped Lincoln signature will set you back a few grand. Instead, my Lincoln collection included a bookcase full of Lincoln mass-market biographies and edited volumes, a nice bust, one significant historic print, a few mugs, salt and pepper shakers, and a weird-but-adorable Lincoln rubber ducky.

My Lincoln collecting was not at all sophisticated, based as it was on a scholarly editor’s pocketbook, but it was great fun and it still gives me much joy. Looking back on my collection now, I understand the value of my kitschy Lincoln stuff for the giggle it inspired in me as I conducted my serious scholarly work and for the little breather it provided from the rarified air of academic history. History should be fun, darn it, and part of the reason I think so many Americans find history boring is because they had teachers who squeezed no fun out of history at all.

I am a historian who squeezes a great deal of fun from the work I am lucky to do. I am also a historian who embraces my historical subjects with a big hug, leaning in and opening my heart as well as my head to my work. I am passionate about finding the humanity of the historical figures I study. I think at least in part, the fun I had collecting Lincolniana humanized Lincoln for me and humanized the scholar in me, too. It allowed me to see Lincoln as a man (and a bobblehead), not as a god or a myth, and to allow my work to delight me. My editing work made an important contribution to Lincoln scholarship, but allowing humor and humanity into the work provided me with balance. My joyful approach to Lincoln rooted my feet to the ground, where history actually lives, and kept my head out of the ivory tower, where history is sometimes self-important and inaccessible.

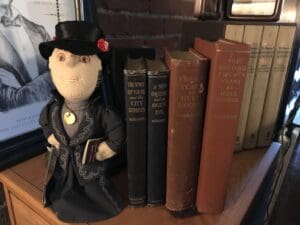

When I started working for the Jane Addams Papers Project in January 2017, I naturally approached Jane Addams in the same way I had approached Lincoln. Joy and a sense of fun balanced my very serious effort to get to know the woman and the social reformer Addams was, to understand her era, and to learn all I could about the fascinating historical contexts of her life. In the beginning of my work with the project, I immersed myself in biographies about Addams, and I studied her surviving correspondence, the speeches she delivered, and the articles and books she published. However, I also immediately coveted the Jane Addams doll that was sitting on a shelf in the project’s offices in New Jersey. All work and no fun is just not my style.

that was sitting on a shelf in the project’s offices in New Jersey. All work and no fun is just not my style.

It took a few weeks, but I found said doll on eBay for $10, and Jane the Doll has been sitting next to or on my desk ever since. In her smart gray frock and sensible black hat she stands, with a slight muppet-like smile, holding her memoir Twenty Years at Hull-House under her arm and wearing her Nobel Peace Prize medal around her neck. To me, Jane the Doll is a muse, of sorts, juxtaposed as it is to the ever more solemn nature of the life-changing reform work in which the real Jane Addams was engaged. I also like that the doll is the silly to Jane Addams’s serious. It is, as well, a daily physical reminder that while my work may be a scholarly business, it is also an honor and a pleasure. I actually get paid to do work I love, so why not embrace the passion and the fun within it.

As I did with Lincoln for twenty years, I now do with Jane Addams. I balance the serious with the silly. I admit it is sometimes harder to find the funny bone in Miss Addams than it was to find it in Mr. Lincoln, but that is no bar to my finding levity in the painstaking and labor-intensive scholarly editing work I do. Collecting my subjects is my way of bringing fun into my life as a historian, so it was exciting for me to learn it will be well within my financial reach to collect first editions of each of Jane Addams’s published books (five already down six to go!). Although memorabilia of Addams is far more rare than it is for Lincoln, in my growing collection of Addams kitsch, I have already added a peace poster for the wall, buttons with “I Love Jane Addams” and “I love Peace,” a coffee mug, and a “Peace, Love, and Jane Addams” t-shirt. Only recently, however, did I realize that a Jane Addams document could be available to me for purchase.

buttons with “I Love Jane Addams” and “I love Peace,” a coffee mug, and a “Peace, Love, and Jane Addams” t-shirt. Only recently, however, did I realize that a Jane Addams document could be available to me for purchase.

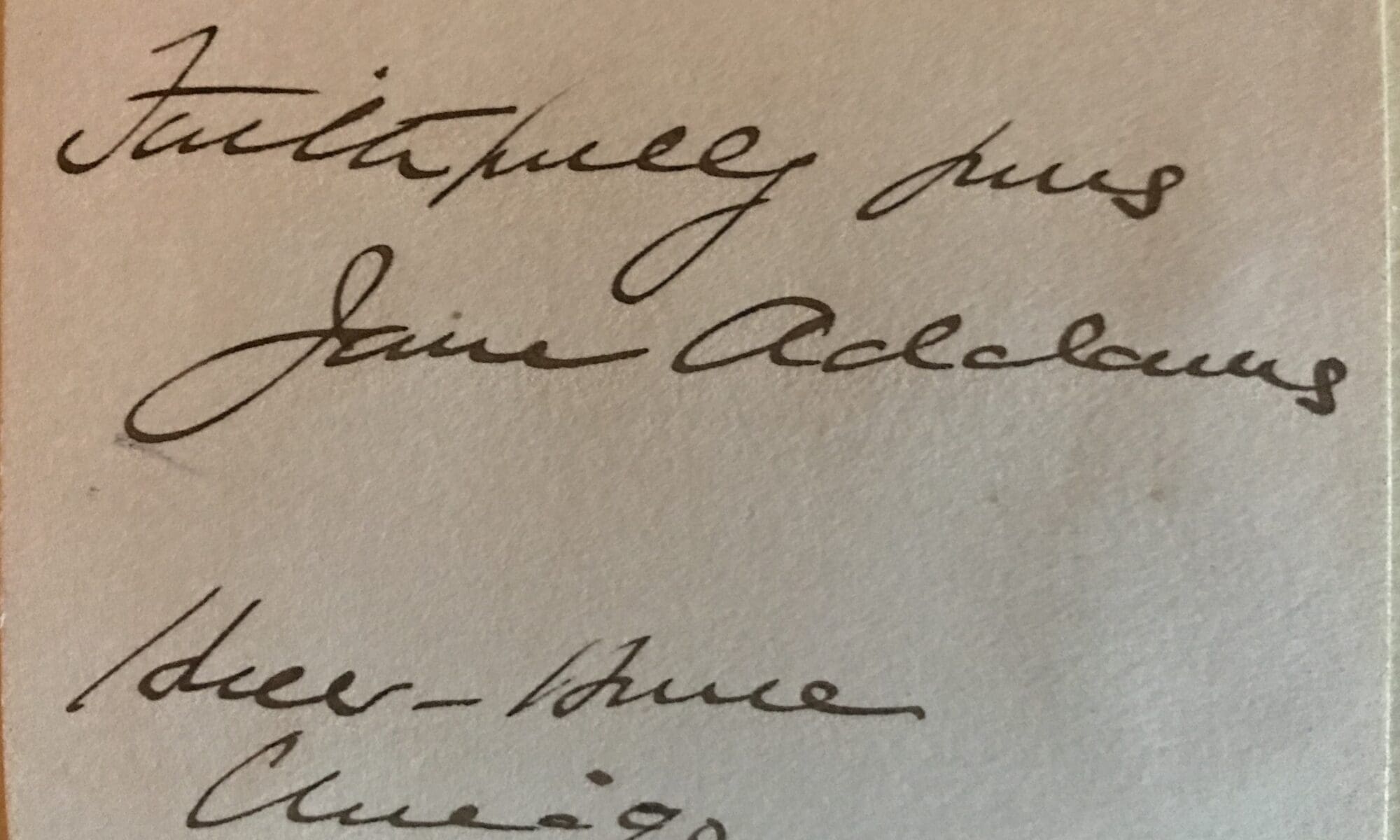

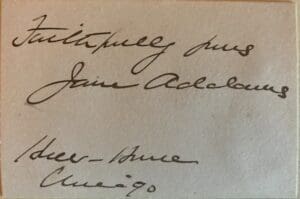

A few weeks ago, I traveled to Springfield, Illinois, for a Lincoln event and to meet up with a group of people who have come into my life through our shared interest in Abraham Lincoln. One of those people who joined me in the sunny beer garden across from the Lincoln Home that afternoon brought me a surprise from the rare bookshop where he works: a printed calling card signed by Jane Addams! It is not a historically important note or a romantic letter to Jane’s beloved Mary Rozet Smith. It is not large, measuring just a 3½ by 2¼ inches. It is not in perfect condition, either. In fact, it has some damage on the printed side from glue which held it in position in an album or adhered it to matting within a frame, and one blob of gluey residue obscures the printed script of “Hull-House.” However, the handwritten side is pristine and features legible-for-Jane-Addams scrawl and her characteristic loopy signature. It is a humble document, indeed, but its imperfections do not lessen my enchantment with it.

Holding that little note in my hands for the first time tendered a tangible spark through my fingers and up to my heart, sending me back in time 100 years. To noisy, dirty, Progressive-Era Chicago. To Hull-House in the city’s impoverished and overcrowded 19th Ward. To Jane Addams, “the world’s best-known and best-loved woman” of her time, standing in the doorway. Handling a historic document has always been for me a kind of handshake with the historical figure of the past who wrote it. Over the years of searching for Lincoln documents in repositories across the country, I shook hands with Lincoln a great many times. But because I work with digital copies of documents at the Addams Papers, this was the first time I had the pleasure of this special and particular introduction to Addams. My day trip to Springfield got even better when I carried that little scrap of Jane Addams handwriting home for fifty times less than it would have cost me had Abraham Lincoln been the one who had penned it.

It annoys me to know that the manuscript market is as sexist as the world. To deem as practically worthless a handwritten note with a fine signature, written by a woman who was the most significant reformer of the Progressive Era, is, I think, almost a crime. But the market’s misjudgment and loss is my gain, allowing me to own a piece of historical magic. My little Jane Addams note is priceless to me. It is the star of my collection of Addamsiana, and I plan to have it conserved and encased in a two-sided archival frame. I do not have aspirations to collect additional documents in the hand of Jane Addams. This one will be enough for me (at least for now, I think). It conjures the handshake, inspires my joy, and provides a palpable human connection to a woman I get to hang out with five days a week.

Anyway, from the perspective of historical memorabilia, in going from a $1 Lincoln rubber ducky to a signed Addams note worth about 100 bucks, I’ve come a long way, baby. Maybe not the equivalent of Jane Addams getting the right to vote, but still super cool for this historian, who is having way too much fun.

By Stacy Lynn, Associate Editor

Jane Addams attended Rockford Female Seminary and was among the first class to receive a Bachelors degree. At Rockford she honed skills that would later be used in her career as the founder of Hull House, leader of the Suffrage, Settlement and Peace movements and her literary career as author of 11 books and hundreds of journal and magazine articles. At Rockford she was the Valedictorian, Editor of the school newspaper, President of the Debate Club and President of her class.

Jane Addams attended Rockford Female Seminary and was among the first class to receive a Bachelors degree. At Rockford she honed skills that would later be used in her career as the founder of Hull House, leader of the Suffrage, Settlement and Peace movements and her literary career as author of 11 books and hundreds of journal and magazine articles. At Rockford she was the Valedictorian, Editor of the school newspaper, President of the Debate Club and President of her class.