I recently took a course on Gephi, an open-source network visualization tool offered by the Programming 4 Humanists group at Texas A&M University. This three-session Zoom-based course, taught by Katayoun Torabi was a great entry to a digital humanities topic that I have long been interested in.

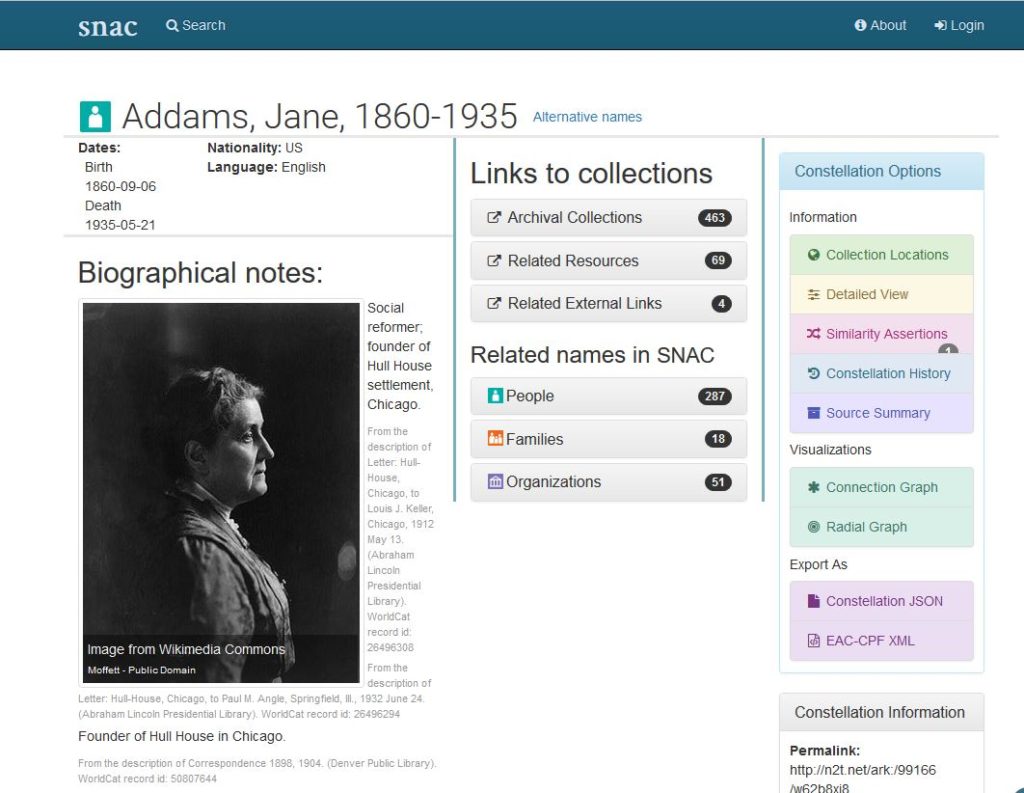

One of our long-range goals at the Jane Addams Papers Project is to make the underlying data in the digital edition accessible so that digital humanists can use it for research. Having a chance to play around with network visualizations helped me to think through how we might use this tool to understand Jane Addams’s life and her causes in new and interesting ways. It also helped me better understand what we need to do to make data from our edition available.

A few ideas popped out immediately:

-

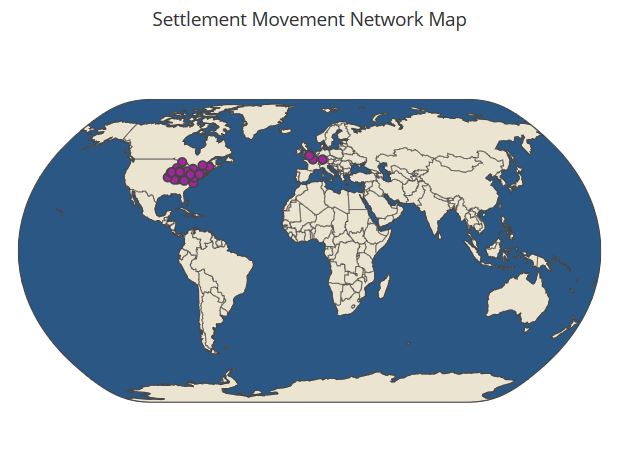

- a visualization of Addams’s correspondence, modeled on the ideas used to create the Mapping Republic of Letters project at Stanford.

- a visualization of how people in the Addams’ digital edition were connected via organizations, looking at for example, the interactions between women involved in the suffrage movement and the peace movement.

In this post we will look at correspondence networks.

Thinking About Data

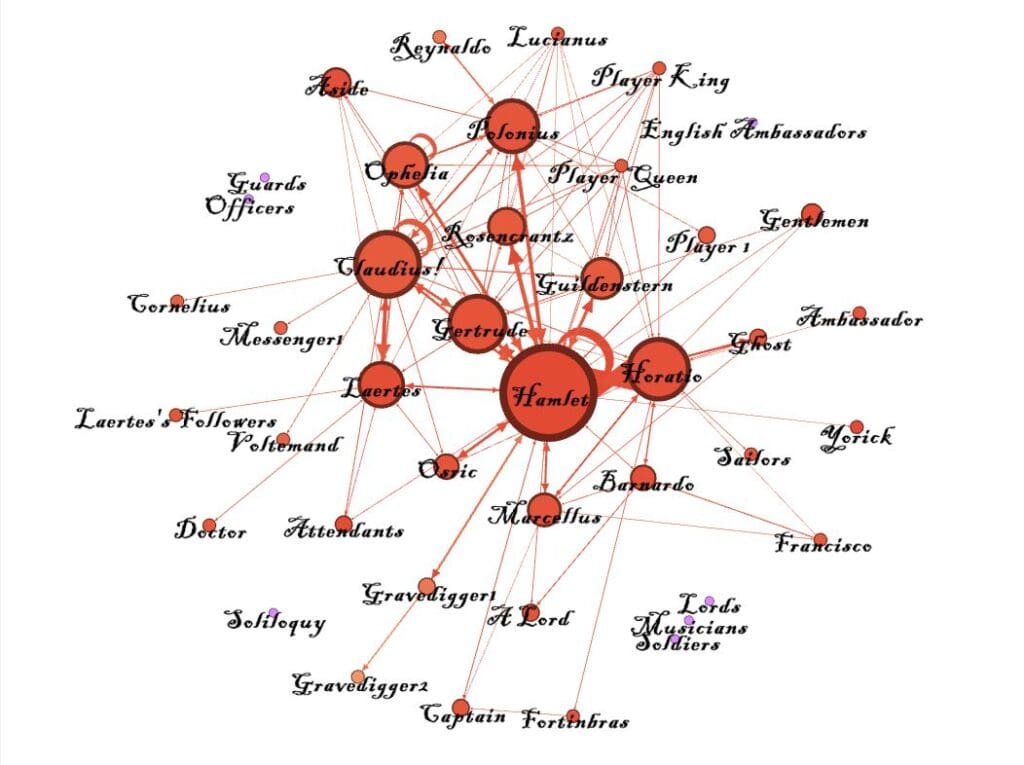

The examples that Katayoun used in our class were all drawn from literature. We mostly worked with data from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, looking at instances of speech between characters to create visualizations of how the characters related to one another.

What struck me almost immediately was that the difference between this kind of analysis and what I hoped to do, was that with a literary work (or any single historical record), this analysis can provide an accurate representation of that text. As I thought about how we could this tool to understand the Jane Addams Papers, the problem of incomplete data reared its ugly head.

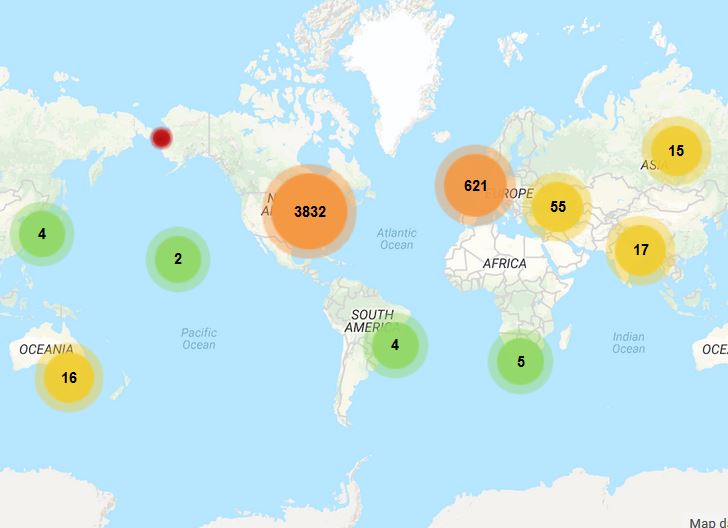

We have to understand that any visualization of the Jane Addams papers cannot fully be a visualization of Jane Addams’ life. Addams’s papers are incomplete. We are missing many of Addams’ most intimate letters between family members and her long-time companion, Mary Rozet Smith. At best, we might be able to visualize more of her professional life than her personal one. But we are also missing many, many letters sent to colleagues and acquaintances that never made it into archives and private collections. Many of the papers of Addams’s European counterparts did not survive World War II. So what we are left with is an impression, a partial glimpse into her world, but an imperfect one.

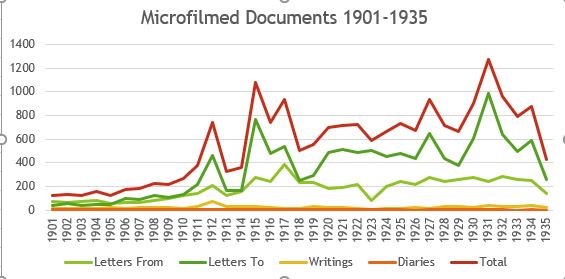

What can counts of letters tell us about Addams’ life? When I first took on editing the Addams Papers, I tried to estimate (by counting entries in the microfilm edition index) how many documents we had in the base collection so that we could estimate how long the project would take. Even as basic a visualization as the one below can help you see the broadening of Addams’s life as she moved from a local activist to one who operated on a global scale. It can give a rough visualization of when things happened in her life.

This red line (total documents) gives us a good sense of scale, and also the years where we could expect the heaviest number of documents. In the first ten years (1901-1910) we had low document counts, which rose dramatically in 1912 (Addams’s participation in the 1912 presidential election), 1915 (Addams’s establishment of a peace movement in the U.S. and international peace congresses). Her activity through the 1920s and early 1930s remains high, with peaks in 1927 and 1931 (Addams’s Nobel Prize).

Looking at the lighter green line (letters written by Addams), we see a fairly consistent output until the end of her life. The only outlier is 1923, a year in which Addams was on a tour of Asia and then suffered from serious illness. It is possible she wrote fewer letters, or fewer of them survived. Most of the dramatic peaks come from increases in incoming letters.

Anneliese Dehner, our web developer prepared a spreadsheet that represented the Item Relations for people in our digital edition. I was able to work with that in a rudimentary way to explore Gephi.

Nodes and edges

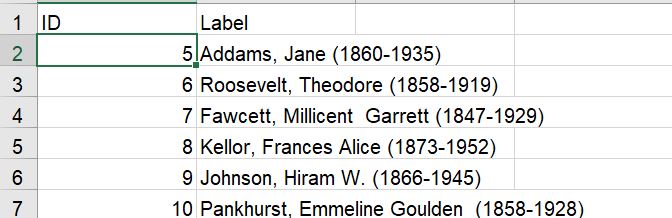

In network visualization there are two tables of information, nodes, which are unique objects, and edges, which link nodes by some kind of action. The hard work of network visualization is gathering all this data so that it can be displayed by Gephi or any other tools.

-

- For a correspondence network, the NODES are the people in the database. They get an ID (in our case the Omeka ID number on our database) and a LABEL (the name of the person).

-

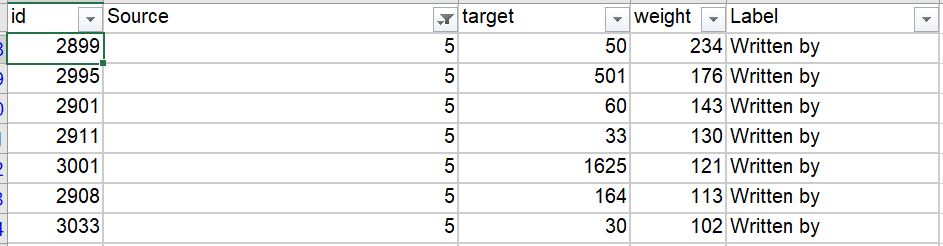

- The EDGES represent the letter. They contain an unique ID, a SOURCE (the ID number of the author of the letter) a TARGET (the ID number of the recipient of the letter) and a WEIGHT (the number of times that that same combination appears). They can also have a LABEL (the relationship — in this case “Written by”). The most common recipient, with 234 letters, is Sarah Alice Addams Haldeman (#50), the sister of Jane Addams. In second place is Emily Greene Balch (#501), a co-worker in the peace movement, donor Anita Blaine McCormick (#60) in third place, and social worker and settlement founder Lillian Wald (#33) in fourth place.

-

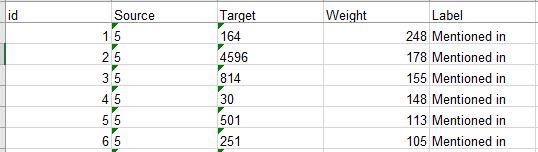

- Another table of EDGES describes the people who were Mentioned in a document, not just the authors or recipients. This might get at a more representative understanding of Addams’s network because one could surmise that important people might be mentioned in letters even if the correspondence between those two people might be lost. And here we do see different results. On this table Mary Rozet Smith (#164), Addams’s companion comes out at the top, with Woodrow Wilson (#4596) coming in second, donor Louise DeKoven Bowen (#814) in third place, and Addams’s niece, Marcet Haldeman-Julius (#30) in fourth place.

Basic Visualization

My first visualization of the mentions data was, to be frank, underwhelming, unless you like big black boxes of goop!

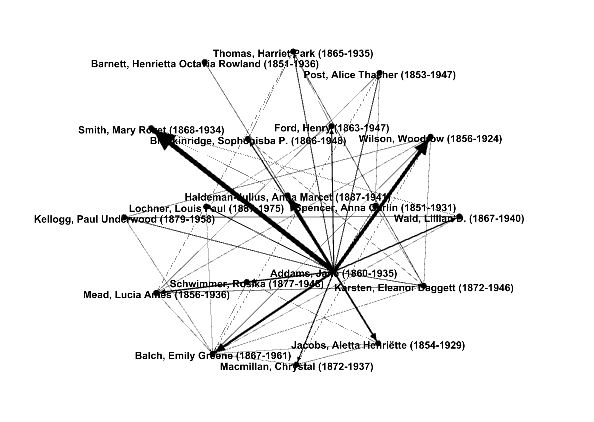

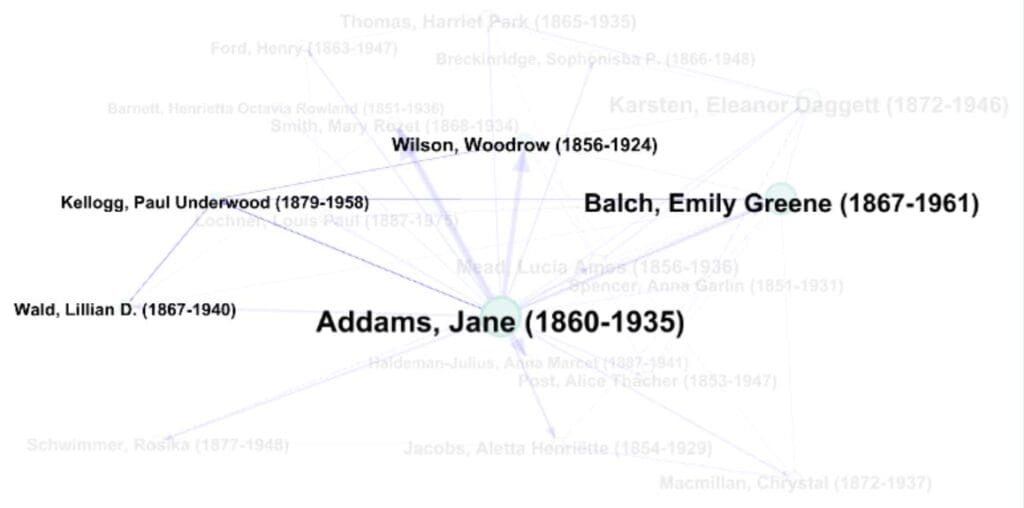

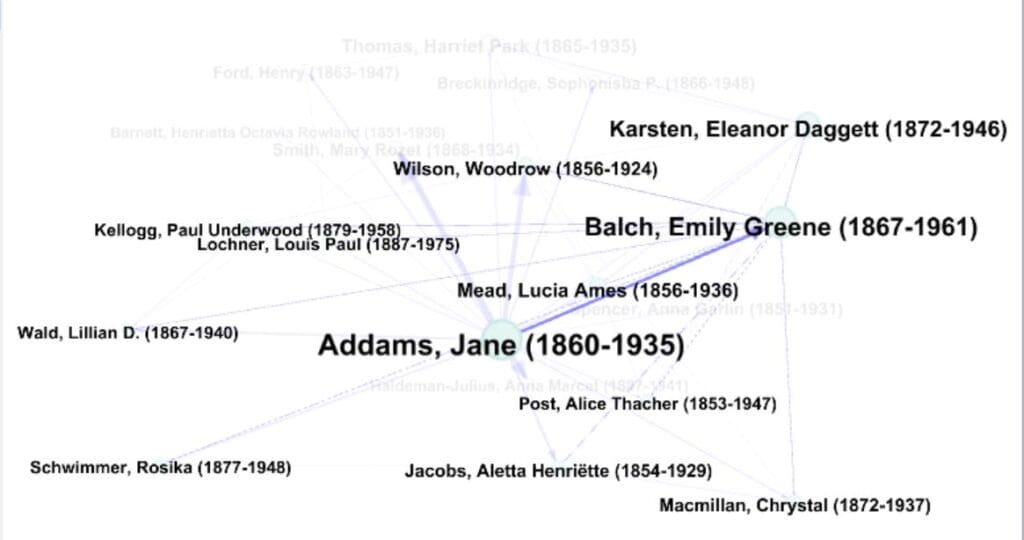

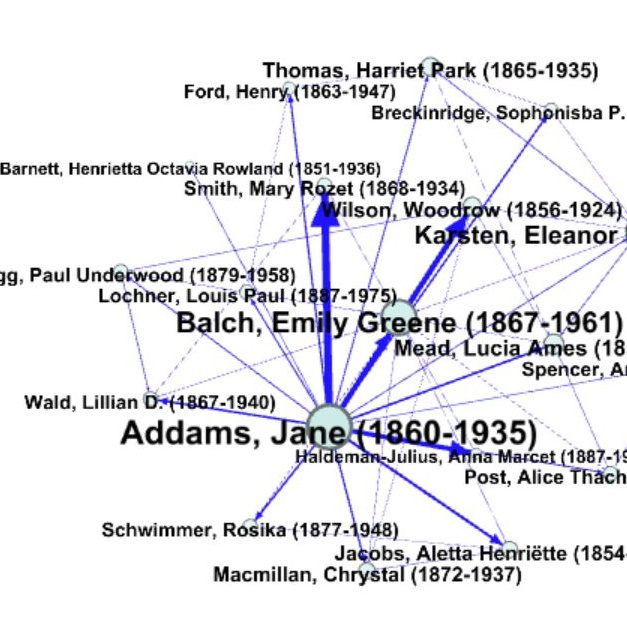

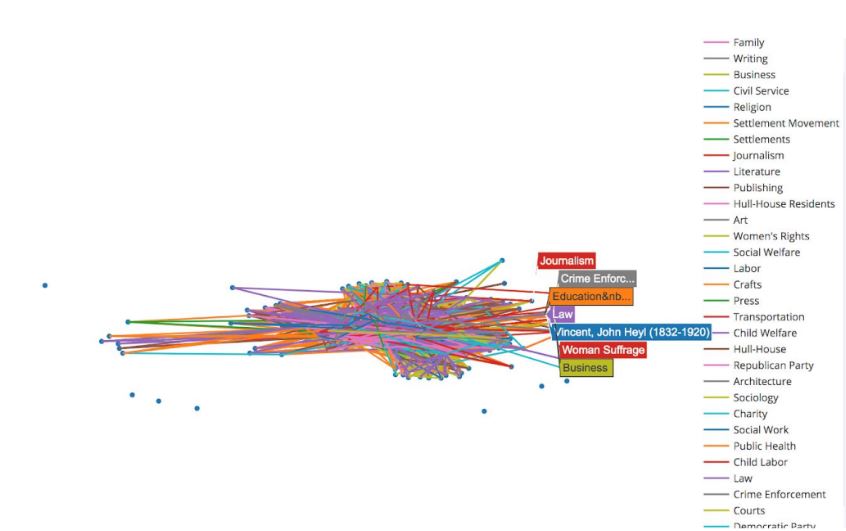

We have over 10,000 names in the NODES table. To get to a visualization that is more legible, I excluded edges with less than 10 mentions in the correspondence. Now that is readable! The weight of the line indicates the number of mentions.

I played with the appearances of our networks to make them easier to understand. Making the labels and the circle sizes proportional to the number of mentions allows you do see things more clearly.

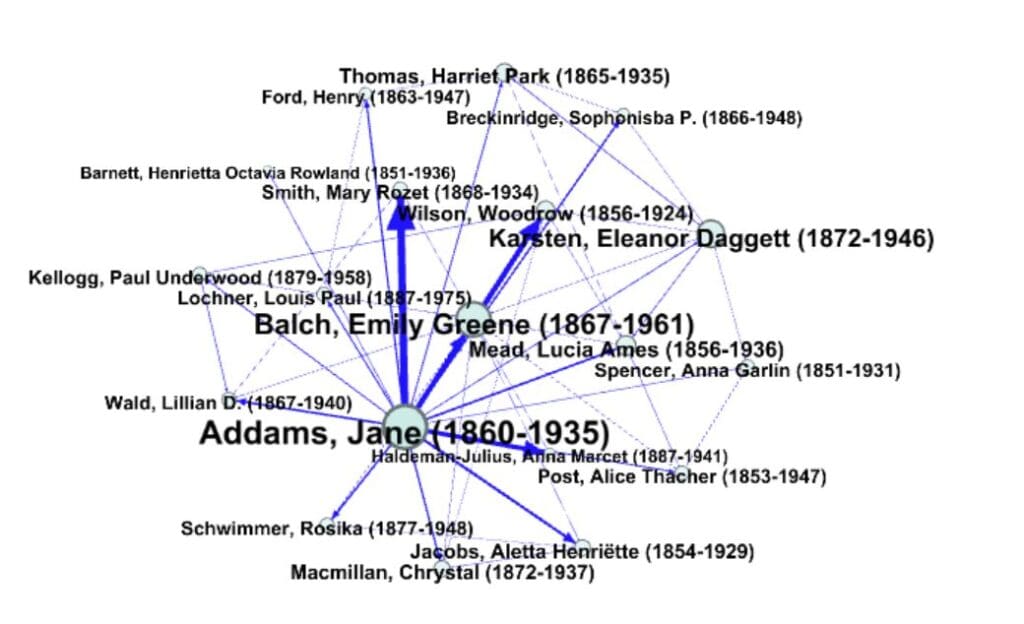

The visualization is interactive. If I click on Paul Kellogg’s circle, only those names associated with him are highlighted– in this case a small subset of the network.

While Emily Greene Balch, a peace activist, is far more interconnected.

The idea here is to explore the various networks that Addams built in her work for peace, social justice, social work, and other causes.

Next steps

Generating the data to build the NODES and EDGES tables requires some work, and filtering the data to get a meaningful result will be critical to creating data sets that the public can use. Our goal is to make this kind of data accessible to students and digital humanists to explore data visualization and Jane Addams.

We are still adding documents to the digital edition, so the first step may be building a dataset of correspondence for each year that we have completed.

In my next post, I’ll look at building a network using our data on people and organizational membership.

story of his life. When I read his letter to Addams, I recalled that Lindsay had written a poem about her, inspired by her peace trip to Europe in 1915. However, I was unaware he knew Addams personally nor that he had corresponded with her. The Jane Addams Digital Edition includes four letters from Lindsay to Addams, each revealing something of the poet’s respect for and fascination with Addams and with Hull-House. In an October 1916 letter, Lindsay proclaimed: “I have loved you a long time dear lady.”

story of his life. When I read his letter to Addams, I recalled that Lindsay had written a poem about her, inspired by her peace trip to Europe in 1915. However, I was unaware he knew Addams personally nor that he had corresponded with her. The Jane Addams Digital Edition includes four letters from Lindsay to Addams, each revealing something of the poet’s respect for and fascination with Addams and with Hull-House. In an October 1916 letter, Lindsay proclaimed: “I have loved you a long time dear lady.”

We are delighted to announce that the

We are delighted to announce that the

Cathy led off the panel talking about the “Big Picture: Conceiving a Digital Edition of Jane Addams’ Papers,” providing a short history of the Addams Papers microfilm and book projects, and the process that went into deciding to digitize the microfilm edition. The decisions to be made involved thinking through the audience for the edition and what kinds of tools and resources they needed. In addition, Cathy discussed the decision to use the Omeka database-driven platform for the digital edition rather than using text encoding using XML. Going with a web-publishing friendly system allowed the Addams Papers to design a site that not only provides deep metadata, but also manages the project’s internal workflow, tracking information on each document as it passes through our permissions and copyright checks, metadata and transcription, and proofreading. Cathy also talked about her desire to see the Addams Papers edition be flexible enough that scholars and students can use its materials to build their own research projects.

Cathy led off the panel talking about the “Big Picture: Conceiving a Digital Edition of Jane Addams’ Papers,” providing a short history of the Addams Papers microfilm and book projects, and the process that went into deciding to digitize the microfilm edition. The decisions to be made involved thinking through the audience for the edition and what kinds of tools and resources they needed. In addition, Cathy discussed the decision to use the Omeka database-driven platform for the digital edition rather than using text encoding using XML. Going with a web-publishing friendly system allowed the Addams Papers to design a site that not only provides deep metadata, but also manages the project’s internal workflow, tracking information on each document as it passes through our permissions and copyright checks, metadata and transcription, and proofreading. Cathy also talked about her desire to see the Addams Papers edition be flexible enough that scholars and students can use its materials to build their own research projects.