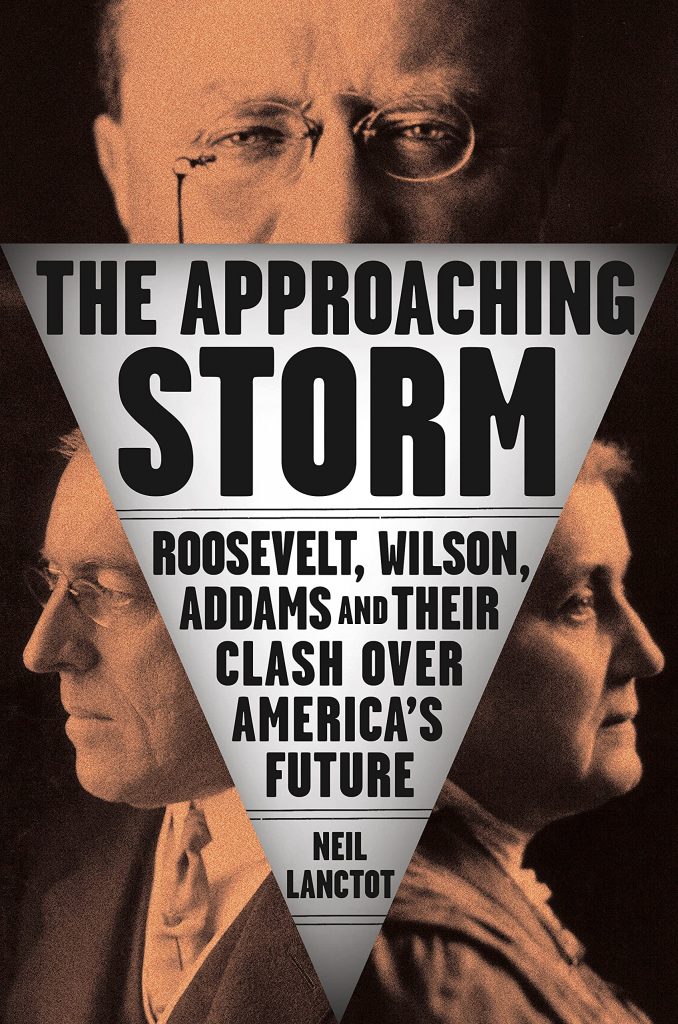

By Neil Lanctot

The onset of a brutal global war in the summer of 1914 shocked Jane Addams and other American pacifists who were certain their cause was gaining widespread acceptance. “Nobody who was not a mature person…can realize now how remote, how unbelievable, a European war then seemed,” her friend Alice Hamilton later wrote. “Believing as we did then in the slow but sure progress of the human race, we looked forward to nothing worse than sporadic outbursts in such unknown regions as the Balkans or South America, never in the highly civilized countries of the Europe which we knew so well.”

The onset of a brutal global war in the summer of 1914 shocked Jane Addams and other American pacifists who were certain their cause was gaining widespread acceptance. “Nobody who was not a mature person…can realize now how remote, how unbelievable, a European war then seemed,” her friend Alice Hamilton later wrote. “Believing as we did then in the slow but sure progress of the human race, we looked forward to nothing worse than sporadic outbursts in such unknown regions as the Balkans or South America, never in the highly civilized countries of the Europe which we knew so well.”

For Addams, a war of this scope (“an insane outburst,” she called it) meant “a changed world,” a world where the rising tide of militarism would undermine the cherished progressive social reforms she had tirelessly advocated over the prior two decades. “It will be years before these things are taken up again,” she told a reporter, “The whole social fabric is tortured and twisted.”

Almost immediately, Addams concluded that the war was likely to be a watershed event in human history and America would have an enormous role to play. But military involvement, she believed, was not the answer. America’s job, as she saw it, was to find a way to bring the belligerent nations to the peace table, alone or with the assistance of other neutral powers. “The United States,” she observed, “with all neutral nations, should throw every bit of its power into the scale for peace.”

Her activities to achieve this goal in the months ahead were both remarkable and extensive: leadership of an unprecedented female-run organization – the Woman’s Peace Party; a fascinating journey through Europe in 1915 meeting with the heads of state of Germany, France, England, and other belligerent powers; and involvement with the “Peace Ship” scheme of the eccentric mogul Henry Ford. But she would pay a price for her pacifism as the war raged on. The onetime most beloved woman in the nation, the so-called “American saint,” would find herself viciously criticized for daring to question American foreign policy and the need for a military buildup at home. Letters and editorials denounced her as an “ancient spinster,” a “crack-brain old creature who ought to be restrained in some institution,” and a “foolish, garrulous woman” who was “badly overrated.”

Theodore Roosevelt, her old friend and colleague in the Progressive or Bull Moose Party, also soured on Addams. To TR, the nation’s rather modest defenses needed to be drastically strengthened if the United States wished to be a global force for good. Any peace efforts at present, he believed, were terribly misguided if not dangerous. As for Miss Addams and her female supporters who had journeyed abroad in 1915 to participate in an international women’s peace congress, they were a “disgrace to the women of America.”

Roosevelt’s hated enemy, President Woodrow Wilson, appeared more sympathetic. Wilson’s determination to avoid war with Germany despite repeated provocations (most notably the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915) cheered Addams immensely in the early years of the conflict. He was also willing to keep in regular contact with her, so much so that Addams and other pacifists truly believed they had a real friend in the White House. Privately, Wilson was not especially receptive to her constant urging that America should act now to bring about peace. Still, as a skilled politician, he was careful not to show his hand. His advisor and close friend Colonel Edward House well understood the importance of Addams. “Her following,” he admitted in his diary, “is large and influential.”

By the fall of 1916, Wilson was finally ready to act. Germany, he knew, was eager to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, even if it meant embroiling the United States in the war. Wilson’s peace move that December, though it accomplished nothing, delighted Addams, as did his “Peace Without Victory” speech to the Senate a few weeks later. But his attitude soon changed once the Germans decided they could wait no longer. Hoping to win the war in 1917, they planned to unleash their submarines to their full potential as of February 1.

To many Americans, the new submarine policy and subsequent diplomatic split with Germany suggested that war was now inevitable. Addams believed otherwise. After all, Wilson had repeatedly told the pacifists he did not want war. “Thank God Woodrow Wilson is President,” one enthused. When Addams and her peace colleagues went to see Wilson in late February, she still thought he could be reached. But the President was uninterested in any of their proposals to avoid war and seemed convinced that his own participation in the peace process was absolutely essential. “I found my mind challenging his whole theory of leadership,” Addams later wrote. “Was it a result of my bitter disappointment that I hotly and no doubt unfairly asked myself whether any man had the right to rate his moral leadership so high that he could consider the sacrifice of the lives of thousands of his young countrymen a necessity?”

A disillusioned Addams watched Wilson take the country into war a few weeks later. She rejected the popular belief that the war was a necessary evil to achieve a better world or prevent future wars. Nor could she understand why Wilson refused to seriously consider alternatives such as the conference of neutrals or “continuous mediation” proposals she had championed. It was, in her nephew James Weber Linn’s words, “the only defeat that she could not forget.” “It seemed to me quite obvious,” Addams later wrote, “that the processes of war would destroy more democratic institutions than he could ever rebuild however much he might declare the purpose of war to be the extension of democracy.”

During the years of American involvement, she found herself increasingly outside of the mainstream, now worked into a war-fueled patriotic frenzy. Not surprisingly, most Americans were now openly hostile to anything “that woman” had to say, especially what they interpreted as “pro-German twaddle.” The vitriol dissipated somewhat after she began making speeches for the Food Administration, a new agency which emphasized production and conservation of food for the war effort. Still, the American public remained suspicious of her pacifist activities throughout the war and the decade that followed. Addams, some still believed, was the “most dangerous woman in the country.”

By the 1930s, when many Americans began to see involvement in World War I as a tragic mistake, Addams’ pacifist activities no longer seemed so threatening. Praise and accolades were showered upon her, ranging from selection to Good Housekeeping’s list of the twelve “greatest living women” in 1931 to the Nobel Peace Prize that same year. Much to her credit, she never distanced herself from her unpopular wartime stance. “We of course never imagined that we could bring the war in Europe to an end,” she explained to journalist Mark Sullivan in 1933, “but we did hope that a body of neutrals with no diplomatic power of course, sitting continuously, might be able to make suggestions for peace which would shorten the conflict.”

That such proposals had only a slim chance of success during World War I never deterred Jane Addams. “She felt,” her niece Marcet Haldeman later wrote, “that any gestures, any proposals of a pacific nature were infinitely more sensible than such mass murder.”

For more info or to order this new book, see The Approaching Storm‘s publisher’s page.