The historical legacy of the Roosevelts is largely associated with progressive change and reform. Theodore Roosevelt’s administration marked the turn of the century with reforms such as the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, a new national park system, and support for labor unions. FDR’s new deal, though the subject of heavy debate among historians, ushered in Social Security for elderly Americans, provided direct federal relief for a struggling American public, and attempted to ensure labor rights through the Wagner Act. Eleanor Roosevelt, aside from her work as First Lady, would go on to serve an important role in the United Nations and assist in the creation of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

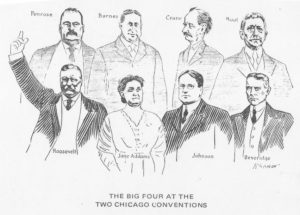

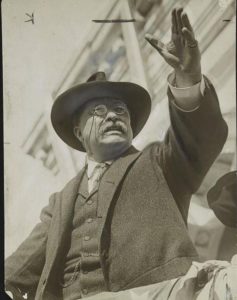

Jane Addams’ relationship with Theodore Roosevelt, or “The Colonel” as he humbly preferred to be addressed, is well understood. Although Addams’ direct participation in politics was sparse, she supported and campaigned for Roosevelt’s Progressive Party bid for president in 1912. Addams didn’t shy away from disagreeing with The Colonel, however, such as over the treatment of African American delegates at the Progressive Party Convention. Despite these disputes, Addams greatly admired Theodore Roosevelt, declaring he “embodied the best things in American citizenship” upon his death.

But what about those other Roosevelts? One would infer that Addams would follow a similar path with Theodore’s distant cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), but the puzzle pieces are less clear. With her health on the decline by the 1930’s, Addams no longer embarked on the large speaking tours of previous decades, which makes some of her opinions difficult to dissect. Despite this fact, she did still offer a healthy handful of writings and statements on the issues of the day, such as the Great Depression and the Roosevelt Administration’s response.

For starters, Addams and FDR knew of each other, at the very least, for many years. Way back in 1912, State Senator FDR invited Addams to speak in Albany about her social work, though it’s unclear if she ever took him up on the offer. FDR would climb the political ranks in the New York State Senate and the United States Department of the Navy before setting his eyes on New York Governorship in 1928. This same year, Addams would endorse Herbert Hoover for President — one of her few presidential endorsements throughout her lifetime. This was largely a result of Hoover’s relief work in Europe a decade prior. It’s unclear who Addams supported in 1932, but one can assume that the Democratic platform of repealing prohibition put Roosevelt in weaker standing in Addams’ esteem. To nobody’s surprise, Addams disapproved of this action from FDR once he assumed office, stating in July 1933 that the eighteenth amendment’s repeal would be “nothing short of a calamity.”

She did, however, write to President-elect Roosevelt in December of 1932 endorsing Frances Perkins for Secretary of Labor. FDR’s appointment of Perkins would make her the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet and eventually one of the longest serving presidential cabinet members in US history.

Addams had positive things to say about the National Recovery Administration (NRA), one of the most noteworthy programs from FDR’s “New Deal.” She praised its efforts to end unemployment and ensure minimum wages, and spoke to the value of business practices being placed on a higher standard as a result of the NRA. Addams described the struggles of the average city workman during the Great Depression, and hailed “That the NRA has come to his rescue fills many of us with sincere gratitude.”

Despite this praise, Addams always maintained a critical eye. She asserted that the NRA “demands careful study” and that the issue of unemployment was complex, requiring greater effort than federal relief alone. While Addams generally supported government assistance, she was always quick to stress the additional importance of the work from community members, private citizens, and social workers. Addams described the importance of this supplementary social service in another writing from the same year, stating “The public relief work is concerned largely with food and clothing and, unhappily, not always with shelter. Our supplementary social services are, perhaps, more necessary simply because people’s lives have been saved by governmental funds and they are distressed about it.”

The New Deal also established the Social Security program, providing welfare and benefits to senior citizens as well as additional unemployment insurance. Addams wrote considerably in favor of old age security in the later years of her life and certainly would’ve had praise for the Social Security Act. Sadly, Addams died three months before the legislation was passed.

Addams and Eleanor Roosevelt had immense mutual respect for one another and offered the highest praise and flattery for each other. In January 1933, Addams introduced Eleanor before a speech at Orchestra Hall, Chicago, and sang endless praises for the incoming First Lady. Addams commended her work with the Women’s Trade Union League, the Foreign Policies Association of New York City, and the Woman’s City Club in New York. She also praised her work in education and her Hyde Park furniture and crafts shop, Val-Kill Industries. Addams aptly added in her remarks “I am sure that some of you listening to my even incomplete list of Mrs Roosevelt’s interests and activities must have been reminded of the abounding energy and unflagging concern for human affairs exhibited by another distinguished Roosevelt, and that you rejoice with me that such a spirit is once more to be domiciled within the White House.”

Eleanor Roosevelt would go on to have a pioneering and invaluable career in the White House and with the United Nations, breaking gender barriers and becoming one of the most influential women of her time. By helping to establish the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in many ways she continued and honored the work which Addams devoted so many years of her life to.

In the final month of her life, Addams was the guest of honor at a Washington D.C. dinner. Here, Eleanor Roosevelt labelled Addams “the greatest living woman.” She also reflected on Addams’ life years later, stating “Miss Addams served humanity so well she should never be forgotten. Anyone who knew her, will remember the inspiration of her presence, but her spirit went far beyond the individuals who knew her. It affected the thinking and living of people all over the world.”

While Addams and the Roosevelts played small roles in each other’s lives and history, they collectively played large roles in the ever-ongoing duty of creating a better world through progressive change.

Sources: Smithsonian Magazine. “The Speech That Saved Teddy Roosevelt’s Life“. Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed January 16, 2024; PBS. “Teddy Roosevelt and Progressivism.” PBS. Accessed January 16, 2024; Addams, Jane, “Statement on the Death of Theodore Roosevelt, January 6, 1919,” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed January 16, 2024; Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library, “Papers As New York State Senator.” 1910-1913; Addams, Jane, “Statement Endorsing Herbert Hoover for President, October 1928,” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed January 16, 2024; Addams, Jane, “Statement on Prohibition, July 8, 1933,” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed January 16, 2024; Addams, Jane, “Statement Endorsing The Appointment of Frances Perkins as Secretary of Labor, December 8, 1932,” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed January 16, 2024; Addams, Jane, “Second Draft of Address on the National Recovery Administration, September 1933,” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed January 16, 2024; Addams, Jane, “Women’s Part in Revealing Human Needs, October 30, 1933,” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed January 16, 2024; Addams, Jane, “Remarks Introducing Eleanor Roosevelt at Orchestra Hall, Chicago, January 20, 1933,” Jane Addams Digital Edition, accessed January 16, 2024; United For Human Rights. “CHAMPIONS OF HUMAN RIGHTS ELEANOR ROOSEVELT (1884 –1962)” accessed January 16, 2024; Barber, Elizabeth. “Jane Addams, world’s ‘best-loved woman,’ honored with Google doodle.” The Christian Science Monitor, September 6, 2013.

James LaForge is a Senior Communication Arts Major at Ramapo College of New Jersey and an Editorial Assistant at the Jane Addams Papers Project.