History is, essentially, the stories of individual people and the interconnectedness of their stories to each other and to the broader history of their communities, their societies, and their world. The intersections of the lives of the historical figures who occupy my historical imagination are fascinating to me, and the people who inspired them are always central to the development of my understanding about their lives and the historical space they occupied. Jane Addams, for example, was an inspiration to an entire generation of female reformers who lived and worked at Hull-House, and the individual work those women pursued made an important impact on Addams’s world view, her writing, and her advocacy for social and economic justice. As well, her fascination with Tolstoy and her childhood memories of Abraham Lincoln offer us insights into the development of her ideas, her ideals, and her visions for reform.

As a historian, I spend a great deal of time thinking about these human connections of the past. The close relationships of the historical figures I study—like the intimate friendship between Jane Addams and Mary Rozet Smith or the professional relationship Addams shared with reformer and settlement worker Lillian Wald—offer obvious clues about Addams’s personal and professional life. The intersection of these particular personal stories tell me much about the lives of women in the first part of the 20th century, the network of Progressive Era reformers, and the conditions of life in the urban environments of Chicago and New York City. But as an enthusiast of the past, it really gets interesting for me when I chance upon an unexpected or less obvious historical connection. It is particularly thrilling when that connection also resonates in some way with my own personal story or relates to other historical interests I entertain.

Recently, I was doing some editorial work on a set of documents dated just days after American entry into WWI. One document was a letter to Jane Addams, dated April 9, 1917:

My Dear Friend:

What shall I do? This war breaks my heart. Send me what you have written since [William Jennings] Bryan enlisted — for instance. Are you with Bryan? Do you accept President Wilson’s war message on its face value? Is that final with you?

I hate a hyphenated American. I hate war. But I owe no one in Europe a grudge. I would rather be shot than shoot anybody. If I had been in Congress I would have voted with Miss [Jeannette] Rankin and would have considered it a sufficient reason to say “I will not vote for war till she does.”

Please write me a tract, or send a clipping. With all respect

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay

Vachel Lindsay was a poet and performing artist who is relatively unknown today. He lived and worked in Springfield, Illinois, where I lived and work myself for more than twenty years;, and, therefore, I am well acquainted with his body of work and the  story of his life. When I read his letter to Addams, I recalled that Lindsay had written a poem about her, inspired by her peace trip to Europe in 1915. However, I was unaware he knew Addams personally nor that he had corresponded with her. The Jane Addams Digital Edition includes four letters from Lindsay to Addams, each revealing something of the poet’s respect for and fascination with Addams and with Hull-House. In an October 1916 letter, Lindsay proclaimed: “I have loved you a long time dear lady.”

story of his life. When I read his letter to Addams, I recalled that Lindsay had written a poem about her, inspired by her peace trip to Europe in 1915. However, I was unaware he knew Addams personally nor that he had corresponded with her. The Jane Addams Digital Edition includes four letters from Lindsay to Addams, each revealing something of the poet’s respect for and fascination with Addams and with Hull-House. In an October 1916 letter, Lindsay proclaimed: “I have loved you a long time dear lady.”

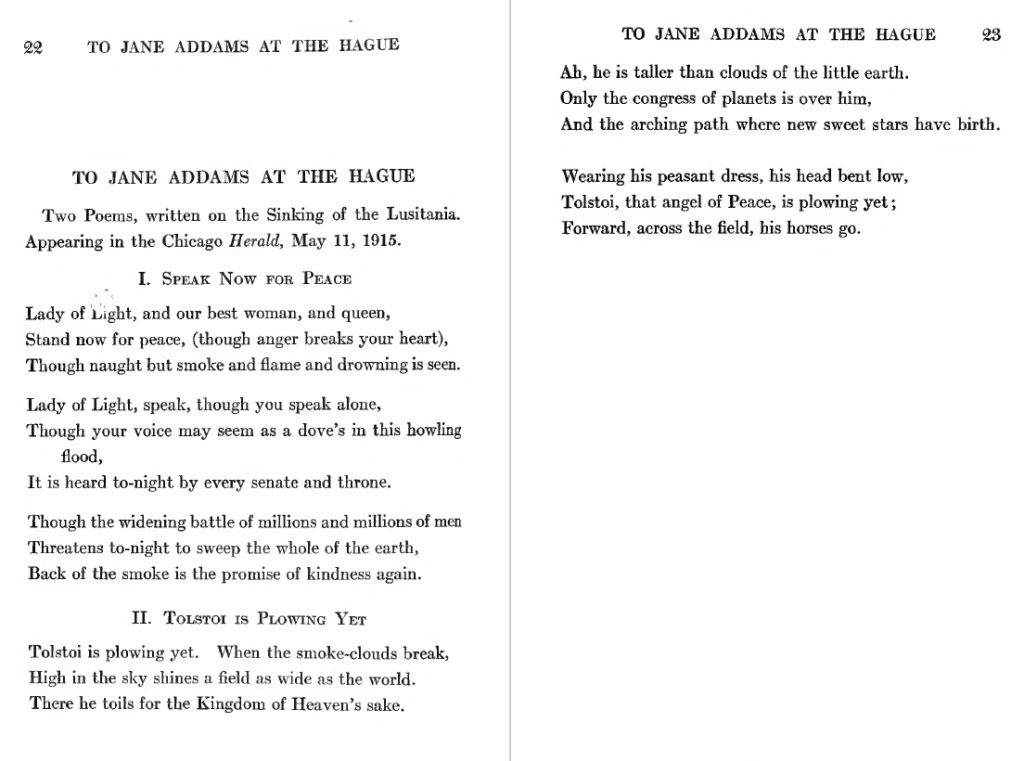

That love had, indeed, inspired the poem I had remembered, “To Jane Addams at The Hague,” which Lindsay first published in the Chicago Herald in May 1915 and later as part of his popular 1917 collection The Chinese Nightingale and Other Poems.

In the 1910s, Lindsay spent time in Chicago performing his poems and seeing his literary friends, including the poet and magazine editor Harriet Monroe, with whom Addams was also acquainted. Lindsay frequented Hull-House, where his good friend George Hooker was a resident, and it seems likely he enjoyed at least one or two good talks with Addams. It is unclear when he might have been formally introduced to her, but in April 1916 he wrote her a letter indicating they had been corresponding for some time. That letter was a reply to a letter from Addams, and in it Lindsay sent her his wish that they may soon see a moving picture show together. There are no known extant letters of Jane Addams to Vachel Lindsay, but the content of his letters to her indicates she had some interest in the young man and his work, and in a speech in 1922, she quoted Lindsay’s analysis of the new medium of the movies in modern society.

Lindsay, who was associated with a group of celebrated Chicago writers that included Edgar Lee Masters and Carl Sandburg, was a creative and somewhat eccentric young man. He traveled the country on foot, selling his poems to support himself, and he popularized for a time the chanting and singing of poems, often performing them with musical and dance accompaniments. In December 1916, Lindsay invited Addams to one of those performances at the Little Theatre in Chicago. It is unclear if she attended, but there is evidence she invited Lindsay to Hull-House on a few occasions. In October of that year, Addams sent Lindsay a copy of her book The Long Road of Woman’s Memory, and in his letter of thanks he wrote: “I sat down and read it all morning and half the afternoon the minute it arrived. It is a lovely book—the work of a Greek, a woman more Greek than Christian.”

The fact that Lindsay, who was a progressive thinker, admired Jane Addams and her work is not surprising. Addams and Hull-House inspired many artists and writers, as well as reformers and social workers. Nor is it surprising that Lindsay, who spent time in Chicago and who interacted with people in the orbit of Hull-House, had a personal acquaintance with the famed settlement worker. What is surprising, and fascinating, too, is that Lindsay experienced a strong emotional connection to Addams. His friendship with her his touched soul, as one biographer put it. Lindsay looked to Addams for answers about his anxieties related to the war, sought her approval of his work, and shared with her his fears about failure. “Back of it all is the hope that my book shall be a live thing—a piece of ink-dynamite, not just a book pleasantly discussed by people who read my verses,” he wrote Addams in 1916. “With so many books dying before my eyes—I cannot bear to write a dead one.”

Lindsay had experienced his first hallucinations in 1904, initial signs of the future mental illness that would ultimately cost his him his life; and his breakup with the poet Sara Teasdale in 1914 had been emotionally traumatic for the poet. But by 1916, Lindsay was enjoying considerable literary success, winning awards and selling books. Although four letters is far, far, far from enough evidence to evaluate the emotional importance Lindsay may have been attaching to his friendship with Addams, a close reading of the letters, however, evokes a whisper of the mental distress that was coming. There is a breathless quality to the words and the sentences, and the letters leave me wondering what kind of advice or encouragement Jane Addams may have offered Lindsay in their face-to-face interactions with each other. It is unlikely we will ever know.

What I know for certain, however, is that the relationship between Lindsay and Addams, despite what it may have meant to her on a personal level, is an example of the richness of the interconnectedness of human stories, the broader sphere of one person’s influence in the world. In this case, it speaks to the significance of Jane Addams as an inspirational figure. But it is also one of those delightful connections I am happy to chance upon, which light a spark in my historical imagination and connect my own story to the stories of the past.

Notes: Anna Massa, Vachel Lindsay: Fieldworker for the American Dream, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970, 17, 46, 100-101, 202; Eleanor Ruggles, The West-Going Heart: A Life O Vachel Lindsay (New York: W. W. Norton, 1959), 240, 247, 258; “Lindsay, Vachel (1879-1931), American National Biography; Vachel Lindsay to Jane Addams, October 15, 1916; Vachel Lindsay to Jane Addams, October 29, 1916; Vachel Lindsay to Jane Addams, April 9, 1917; Vachel Lindsay to Jane Addams, June 26, 1917, all in Jane Addams Digital Edition. William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925) was a Democratic politician from Nebraska. In April 1917, he offered his services to the government in the war effort. American National Biography. Jeannette Rankin (1880-1973), a peace activist and Republican politician from Montana, was the first woman to serve in Congress. She voted against the American declaration of war against Germany in 1917. American National Biography; Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. The image of Lindsay is courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

A scholarly editor and historian, Stacy Lynn formerly edited the papers of Abraham Lincoln and currently is an editor at the Jane Addams Papers Project.