Sometimes, we just need to take thirty minutes and read a little history.

In 1926, the United States, which was marking the sesquicentennial of its founding, was not in a particularly democratic mood. Nor were the political, economic, social, and racial conditions of the country reflective of the promise of the U.S. Constitution and the ideals of American democracy. The democratic malaise was so complete, even the Sesquicentennial celebration of the American founding failed to inspire and encourage the body politic.

In 1926, American women had the vote, but Black voters in the South were effectively disenfranchised by Jim Crow policies such as literacy tests, poll taxes, and all-white primaries. Groups like the KKK employed violence and vigilante tactics to terrorize Black, Jewish, and Catholic Americans, as well as immigrants. Immigration at this time was governed by the 1924 Immigration Act—which favored white European immigration, functioned by a rigid quota system, was based on race and “fitness” for American citizenship, and completely barred immigrants from Asia. The purpose of the new act was to preserve a mythological ideal of American homogeneity. On the heels the 1924 act, Congress also established U.S. Border control, which fundamentally altered the U.S. government’s interactions with immigrants. Nativist propaganda was rampant, a growing fear that different cultures would destroy America was surging, eugenics was being seriously discussed, and racial stereotyping was the norm.

In 1926, American law enforcement and politics were rife with corruption and scandal. This was the era of gangland violence in American cities, organized criminals running around armed with machine guns. The Volstead Act (prohibition) had created an underworld of bootlegging and crime and bribery of police officers by rum runners with pockets full of cash. In 1926, Al Capone ruled the underground of Chicagoland, and in September rival gangs shot up his headquarters at the Hawthorne Hotel in a massive drive-by shooting, spraying 1,000 bullets into the hotel’s restaurant.

Cities like New York, Chicago, and St. Louis were rife with political corruption, and the fallout of the corrupt Presidency of Warren G. Harding (1921-1923), most notably the Teapot Dome Scandal, was still coming to light. In Chicago hand grenades (called Chicago pineapples) were used to intimate voters, a U.S. District Court judge for the Eastern District of Illinois resigned after he was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives for abuse of power, and the U.S. Senate investigated a senate campaign in Illinois for campaign finance corruption, one of the candidates caught taking a $125,000 bribe from the director of a public utility. Next door in Indiana, the KKK had infiltrated Indianapolis municipal government and had members in the statehouse, as well. And that is just a modest Midwestern sampling of the political and judicial corruption running roughshod over American law and politics at every level in 1926.

In 1926, American foreign policy was generally characterized by political isolationism and economic nationalism. American wealth was concentrated in the top 5 percent of Americans. Businessmen controlled Congress, and corporations paid low taxes, while two million Americans were unemployed, more than 70 million (60 percent) lived in poverty, and 80 percent had no savings to stave off personal economic disaster. It was the Roaring ‘20s, but it was not roaring good for the majority of working people.

In 1926, the future of the post-World-War world was uncertain. There was considerable unrest across the globe with authoritarian coups in Lithuania, Poland, and Portugal; a general strike in Britain that led to a declaration of martial law. Prime Minister Theodoros Pangalos assumed dictatorial powers in Greece, and the fascist Benito Mussolini increased his power in Italy by cracking down on public demonstrations and abolishing opposition parties following an assassination attempt.

In 1926, fear of fascism and socialism and communism, internationalism and humanitarianism—basically all of the isms—became a rallying cry for the white and rich power brokers who employed the rhetoric of othering to gain political support in communities that should have rejected their politics. During this time, not even the best among Americans were safe from attack.

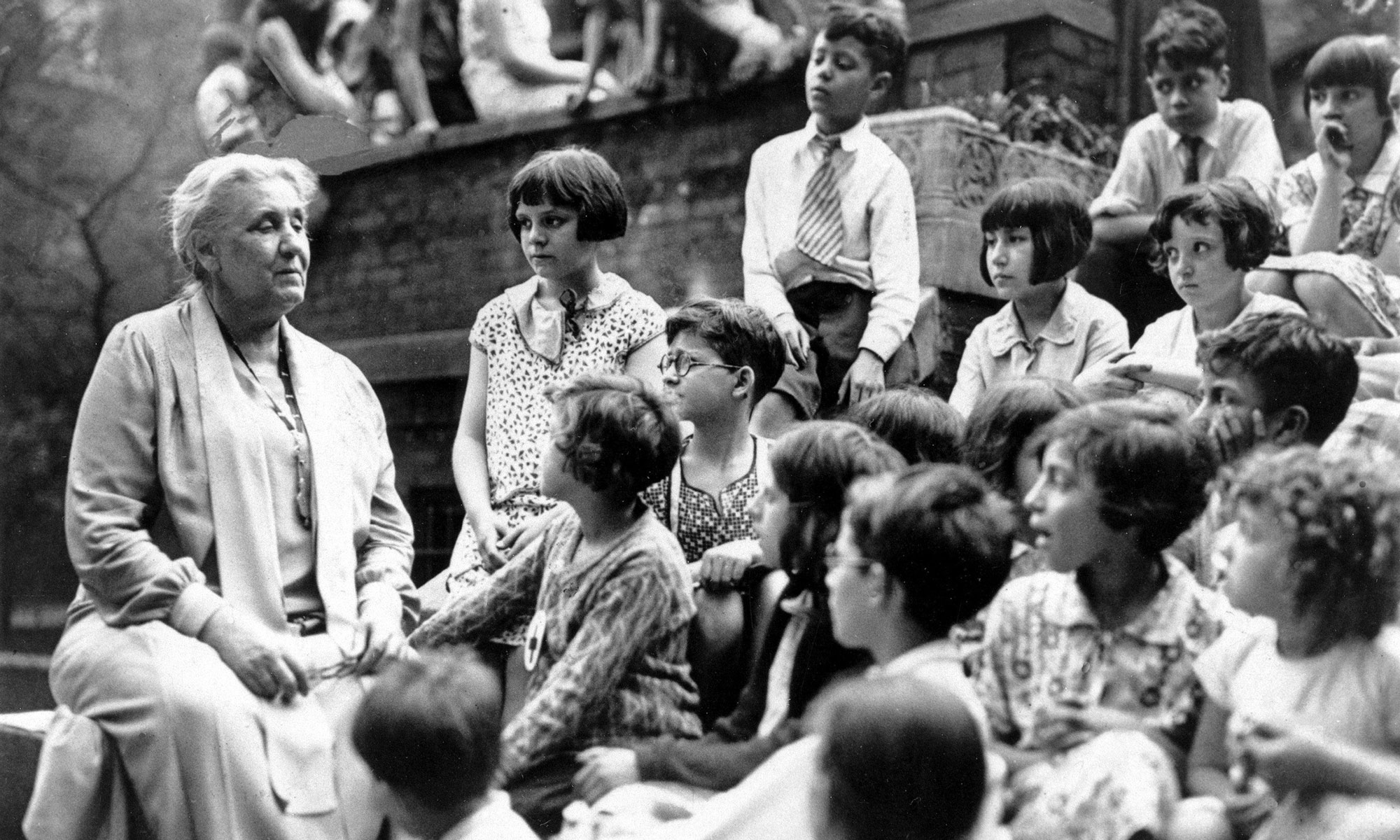

In 1926, Jane Addams was a sixty-six-year old internationally famous and well-respected reformer who had dedicated her entire adult life to improving the lives of vulnerable people. A renowned settlement worker, social philosopher, and orator, she was the author of seven books on democracy, social uplift, peace, and humanitarianism. Since cofounding Hull-House in Chicago in 1889, she had worked to expand democracy, shed light in the darkest corners of American cities, and lobbied for legislation and public policy initiatives to improve the lives of children, women, immigrants, and the working poor in the United States. She was beloved, and most Americans never wavered in their respect for her principled advocacy for a better world. Yet because she was an unflinching advocate for ALL vulnerable people, stood her ground on peace and antimilitarism, and constantly used her public platform to decry injustice and to stand up for free speech, the rule of law, and the ideals of American democracy, the fearmongers, who were smaller in number but so much louder in voice, branded her a dangerous radical.

In 1926, people hell-bent on silencing speech against the U.S. government or others merely seeking to draw attention to themselves and their political, social, or religious views, declared Hull-House a harbor for all of the “isms” and called Jane Addams anti-American. Although she seized opportunities to defend her good work and her reputation throughout the year, she refused to take the bait of the fearmongers, even when many of her friends and supporters urged her to sue for slander. It was not the only time in her life people had doubted or questioned her, and she certainly absorbed a great deal of negative press during World War I when she was unwavering in her position of peace. Yet the assaults in 1926, during a roller-coaster year that included two trips abroad and a heart attack, took their toll. As she wrote Dorothy Detzer, a sharp-tongued feminist and secretary of the WILPF, in November 1926: “I have had a horrid attack from the Commander of the Ill. Div. of the American Legion. I wish you were coming over soon to confront him!”

Some Jane Addams highlights of 1926:

January 14. Jane Addams and Mary McDowell, Chicago commissioner of public welfare, hosted a meeting with Capt. C. B. Hopkins, a member of the Military Intelligence Association who had accused them of being “Reds” because of their association with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). When Addams asked him why he considered her dangerous, he responded: “Because of the good you have done your influence for wrong is far greater than that of any other.” (Statement on Pacifism and Patriotism, Jan. 13, 1926).

January 16. The Chicago Tribune, in an editorial with the headline “Both Wrong and Dangerous,” agreed with Hopkins that “the universal recognition gained by persons like Miss Addams for their good works makes them all the more dangerous when they turn to doctrines of pacifism which no experience supports.” (Chicago Tribune, Jan. 16, 1926, 8).

February 28. In a speech to the United Neighborhood Houses of New York, Jane Addams argued: “It is quite as devoted and loyal as the old type, but it believes that certain humanitarian ends can be achieved only through cooperation between all nations and all races. In the United States … we believe in brotherly love, in international cooperation and goodwill … but we need something beyond words. We need what I may call an emotional shove that will bring us to a reassertion of our birthright, the moral leadership we have always assumed we had. Other countries are for the moment showing more devotion to the advancement of humanity than we are, and to regain our place we need leadership, not so much by the individual as by the group. Women in groups, joined together not only for settlement work but for every other kind of high minded endeavor, can break down these inhibitions in the public mind so that we can assert our moral leadership, and, while working for the best interests of our country, advance the world.” Speech to the United Neighborhood Houses of New York).

March 20. In a speech before the Women’s National Republican Club, Col. Hanford MacNider, assistant secretary of war, called Jane Addams a “professional agitator” because she opposed military training in the public schools. (New York Daily News, Mar. 20, 1926, 7).

April 1. A Sioux City, Iowa, newspaper questioned the patriotism of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), of which Jane Addams was president. “It is believed,” it read, that “these good women have been deceived by the ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing.’ This so-called League for Peace and Freedom starts out with a high sounding title and fairly reeks with expressions of good will and Christian spirit. An investigation into its activities and its associations, however, will show that it is one of the most vicious and unpatriotic organizations in the United States.” When the WILPF demanded a retraction in November, the newspaper retracted its opinion, local American Legion members doubled-down and demanded that the newspaper “reaffirm its belief that certain activities and purposes of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom are disloyal, unpatriotic and inimical to the national safety.” (League For Peace and Freedom Opposed, Apr. 1926).

April 5. Paul Kellogg, editor of The Survey, who had a meeting with Addams in NYC in late March, wrote her: “There was one comment of yours which I have thought over several times since. You visualized how the fear of Russia was sort of a red herring drawn across the nascent forces in American life; just as the fear of France balked things in England during the first decades of the last century. You cited how the suppression of the slave trade was delayed, for instance, because everyone who espoused such a cause was denounced as a ‘red,’ or its equivalent a century back.” He also asked Addams to write an article for The Survey which would celebrate social work, so much of which was under attack, because “there is a great hungriness among folk who are up to their elbows in work for their communities, and who would a prize word from you at this time.” (Paul Underwood Kellogg to Jane Addams, Apr. 5, 1926; “How Much Social Work Can a Community Afford?, The Survey, November 15, 1926, p. 199-201.).

May 24. Addams in a speech at a meeting of the National Federation of Settlements in Cleveland said: “The American people are in a panic. We must help to mitigate the scare, remembering that all this is nothing new. The same thing happened after the French Revolution. Fifteen years ago those of us who felt that child labor, for instance, could be better controlled by the federal government than by the states, simply went about saying so, and nobody questioned the sincerity of our position. But if you say it now you are a Bolshevik. A member of congress once asked me who wrote the proposed child labor amendment to the federal constitution, and where. I told him it was written by Dean Lewis of the University of Pennsylvania, but whether in Philadelphia or New York or Washington I didn’t know. I was willing to find out where he sat, if that was important. “I am reliably informed,” the congressman replied, “that this was written by Lenin, sitting in Moscow.” (Speech to National Federation of Settlements, May 24, 1926).

May 25. During a Chicago meeting of the American Legion Auxiliary, president Mrs. Eliza London Shepherd declared pacifists and “breeders of pacifism” as “the most dangerous menace to the United States; ” and C. B. Hopkins (yep, same guy), continued his “red-baiting” by denouncing Jane Addams again. (Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1926, 31).

June 7. Addams defended herself in this letter to the editor of the Boston Herald: “I am not in any sense a Socialist, have never belonged to the party, and have never been especially affiliated with them. I am certainly not a communist nor a Bolshevik. I am, of course, president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and we have advocated recognition of Soviet Russia, not because we have been in favor of the government any more than we were with that of the Czars. … I do not know why I am called a Bolshevik except as a term of opprobrium that is easily flung about. …” (Jane Addams to the Editor of the Boston Herald, June 4, 1926).

June 9. An article in the DeKalb (IL) Daily Chronicle read: “Miss Jane Addams, addressing a social workers’ conference, pleads with people not to label all settlement work as ‘red.’ This label, indiscriminately applied harms the cause of social progress she says. She’s right, as she often is. Too often we unthinkingly conclude that any person who tries to improve the condition of those less fortunate than ourselves must be a wild and desperate radical.” (The Daily Chronicle, June 9, 1926, 4).

June 12. Morris Ernst, an ACLU attorney, wrote to Addams regarding Captain Hopkins attack on her and the ACLU, writing “In the course of his remarks he spoke of this organization as being directly or indirectly influenced by agents from Russia. … In the opinion of our attorneys, this attack is clearly libelous both against you and against the organization. We should like to bring libel actions against the Chicago Tribune, Captain Hopkins and the Military Intelligence Association. We shall certainly do so so far as the Union is concerned, and if you will permit us, we will take charge of a case for you and handle it ourselves without any embarrassment or bother for you. … The case is so good, that we have no doubt of our ability to win an action. It will be of immense value as putting a quietus on the pernicious activities of men like Hopkins and the Association which he represents.” (Morris Leopold Ernst to Jane Addams, June 12, 1926; Forrest Cutter Bailey (ACLU) to Jane Addams, June 12, 1926).

June 17. Addams wrote to the ACLU: “I am too much of a Quaker to care for lawsuits altho I do hope that the Civil L.U. will proceed against The Chicago Tribune.” (Jane Addams to Forrest Cutter Bailey, June 17, 1926.

November 4. The WILPF demanded a retraction of the libelous attack that the Sioux City, Iowa, newspaper had published back in April. When the paper issued a retraction, local American Legion members, who had urged the publication, doubled-down and demanded that the newspaper “reaffirm its belief that certain activities and purposes of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom are disloyal, unpatriotic and inimical to the national safety.” (Sioux City (IA) Journal, Nov. 4, 1926, 8; League For Peace and Freedom Opposed; Dorothy Detzer to Jane Addams, November 22, 1926.

November 10. Ferre Watkins, of the Illinois American Legion, in a speech to the Illinois Federation of Women’s Clubs said: “Hull House is the rallying point of every radical and communistic movement in Chicago. The leaders of the settlement are attempting to sell out their country to some international scheme from which they vainly hope to realize great things for themselves.” Watkins also accused the WILPF and Addams as its president of interfering “with the Government’s program of training men for service as officers in the defense of the United States” because she disagreed with her country’s policy of military preparedness and spoke up against military training in the public schools. Addams exercised her constitutional right to free speech and petition of her government, but because Watkins disagreed with her politics he sought to brand her as a communist and to silence her. (Statement on Captain Watkins, Nov. 11, 1926).

Twenty-five Hull-House residents signed a quick defense: “We, residents of Hull House, are not ‘leaders’ in any movement, but plain workers, but we feel that the recent assaults upon Miss Addams and Hull House are [too] vicious to be totally ignored. Miss Addams needs no defense at our hands, for no sane person will credit the utterly silly and puerile [charges] leveled at her by Captain Watkins. But we enter emphatic protest against the statement that Hull House is a rallying point for every radical or communist movement. Hull House believes in free speech and free discussion, but it is not in any way committed to communism or any other form of radicalism. The residents of Hull House carry on no propaganda whatever; they teach classes; they direct clubs; they do what they can for the neighborhood in the way of aid, advice, and instruction; they produce plays and supervise other recreational activities. Those who say Hull House is a center of radical or revolutionary activity are either ignorant or irresponsible. In either case, their statements should be resented by all the intelligent friends and supporters of Hull House.” (Hull-House Residents Protest, ca. November 1926).

November 10. Edith Abbott, University of Chicago professor, wrote to Addams: “Mrs. Kohn has spoken to me about that Legion business and I feel very strongly that nothing but a libel suit will stop those people. Mrs. Kohn tells me that Mrs. Rufus Dawes has been also publicly quoting Mr. Watkins and I think you or the Hull-House Trustees really ought to bring a libel suit against her as well as against Watkins. There is so absolutely no excuse for the kind of talk now. During the war when exaggeration ran high no one weighed words very carefully. But it is simply too despicable for people of this sort to go on repeating these gross slanders. It seems to me like the case when T. R. finally sued that editor for calling him a drunkard. It is the only way to stop this kind of irresponsible lying.” (Edith Abbott to Jane Addams, Nov. 10, 1926).

November 12. In a speech at a meeting of National Federation of Women’s Clubs in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Helen Dawes, of Evanston, Illinois, accused the WILPF of having “communistic tendencies.” “I speak freely,” she said, “because Miss Addams herself does not conceal the fact that she does not believe in our ideas of American loyalty.” (Jane Addams is Scored by Mrs. Dawes, Nov. 12, 1926).

November 13. Lucia Ames Mead, a Boston pacifist, wrote to Addams: “I see from the papers that your Legion savages are after your scalp again. … a fund should be raised to take these libels to court and to call a halt to this audacious slander.” (Lucia Ames Mead to Jane Addams, Nov. 13, 1926).

November 13. Margarita Seymour, a civic leader in Illinois, wrote to Addams: “Great people like yourself must carry heavy crosses, but devotion, honesty and truth will be victorious.” (Margarita Petitdidier Seymour to Jane Addams, Nov. 13, 1926)

November 14. Addams wrote to the Woman’s Peace Union: “The Commander of the Illinois Division of the American Legion who made the attack, made me say very absurd things about stripping the uniform from West Point cadets, in a speech he had heard me make against compulsory military training in the colleges. In reply to the reporter’s question I said that I had stuck to my subject and had not mentioned soldiers. This must be the foundation of the report. It seems to me however so desirable to drop the whole matter that I should deprecate prolonging the publicity which has been much exaggerated on both sides.” (Jane Addams to Women’s Peace Union, Nov. 14, 1926).

November 15. Dorothy Detzer wrote to Addams: “I realize how terrible it is for us, but I do wish a good strong libel suit could be started. I think some of these gentleman will have to pay before they stop abusing decent people.” (Dorothy Detzer to Jane Addams, Nov. 15, 1926).

November 15. John Gabriel, a Denver lawyer, wrote to Addams: “It is, indeed, with regret that I learn of the uncalled for and malicious attack made by Captain Watkins, recently named National Commander of the Illinois American Legion upon the wonderful work that you are doing at Hull House. I have known of your work, not intimately in later years so much as in former years, for now more than thirty-three years and I know there is no foundation whatsoever for such a malicious attack. The good you have done is beyond measure of computation. I wish that I might do something to let you know how much it is appreciated by the many people in the United States who have the uplifting view of things, and, also, I wish it were possible for me to do something to assist you in the great work.” (John H. Gabriel to Jane Addams, Nov. 15, 1926).

December 1. From an article in The Progressive, “a Journal Devoted to Advancement and Improvement in Education, Popular Intelligence, Science, Politics and American Welfare Generally: “The reason that many people long ago began to revolt against the patriotic firebrands who see an anarchist, communist or bolshevist in every American citizen who has a political opinion that has not been rubber-stamped by the conventional boob-intellect may be found in such charges as those recently voiced by one Capt. Ferre Watkins, commander of the Illinois American Legion, that ‘Hull House is the rallying point of every radical and communist movement in Chicago.’ Anyone who knows anything about the subject knows that Hull House, as founded and conducted by that great American woman, Jane Addams, as nearly approaches the ideal of practical Christianity as any institution in the world.” (The Progressive 10 [Dec. 1, 1926]).

December 8, 1931. Jane Addams’s steadfast devotion to her principles paid off, of course, because history tends to get it right, in the end. Jane Addams became the first American woman awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace. Within hours of the news, the telegrams and letters of congratulations began flooding in. This telegram from Walter Pyne, a Massachusetts lawyer, was one of the first: “Congratulations you should have received it long ago you are everything that is good beautiful and lovely.” (Walter William Pyne to Jane Addams, Dec. 9, 1931)

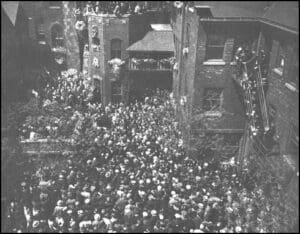

May 21, 1935. Jane Addams died. Thousands of mourners streamed through Hull-House two days later for her funeral. The Chicago Tribune devoted four full pages to her obituary and funeral, hailing her as “America’s Foremost Woman.” (Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1935, 1, 4, 38; May 23, 1935, 9).

2026. Today, Jane Addams is remembered as an icon of Progressive Era Reform and as an American who stood up for the most vulnerable Americans. She is a great hero of American democracy, arguably the equal (or even the better) of leaders like George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Luther King Jr. She made countless contributions to the betterment of the social, economic, political, and educational conditions in the United States. She helped make America more just and more free. She was principled and compassionate, never denigrating others, preferring instead to lift people up, to bring all voices to the table, and always listening and willing to learn and to grow. From much of her work we still benefit today—from the enactment of child labor laws, to woman suffrage, and to the labor protections and the safety of our food that we too often take for granted. There are schools named in her honor across the country; and Hull-House, her home and base of her reform work for more than four and a half decades, is a museum and social justice center on the University of Illinois Chicago campus.

Jane Addams’s name endures because she stood for what is good in America. She wasn’t perfect. She made mistakes, and she owned them. But she walked through all the challenges and celebrations in her life with humility and integrity, compassion for others, a fierce dedication to public service, and, unlike those who attacked her 1926, she refused to wallow in the mud of tearing people down; she never believed that humiliation of one’s opponents was the way to be right. And she never let the critics, the doubters, or the haters make her compromise her principles or shift her moral compass; and no matter who they were or how wrong they may have been, Addams recognized their humanity.

By Stacy Lynn

Associate Editor

Sources: Martin W. Wilson, “Sesquicentennial International Exposition,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia; “The Lasting Legacy of the Johnson-Reed Act,” Tenement Museum, New York City; Tara McAndrew, “The History of the KKK in American Politics,” JSTOR Daily, Jan. 25, 2017; “The Beer Wars and Al Capone’s Bloody Business,” Chicago Stories, WTTW, PBS, Chicago; Daily News (New York), Mar. 20, 1926, 7; 19th Amendment, U.S. Constitution; 41 U.S. Stat. 305; 43 U.S. Stat. 153; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 16, 1926, 8; May 26, 1926, 31; Sep. 21, 1926, 1; DeKalb (IL) Daily Chronicle, June 9, 1926, 4; from Jane Addams Digital Edition (JADE): Norman Matoon Thomas to Jane Addams, Apr. 17, 1926; Edith Abbott to Jane Addams, Nov. 10, 1926; Jane Addams to Dorothy Detzer, Nov. 12, 1926; Jane Addams to Dorothy Detzer, Nov. 18, 1926; Jane Addams to Margaret Dreier Roberts, Dec. 8, 1926. (Note, most of the citations in the calendar entries are documents in The Jane Addams Digital Edition, and those with links are available for viewing).