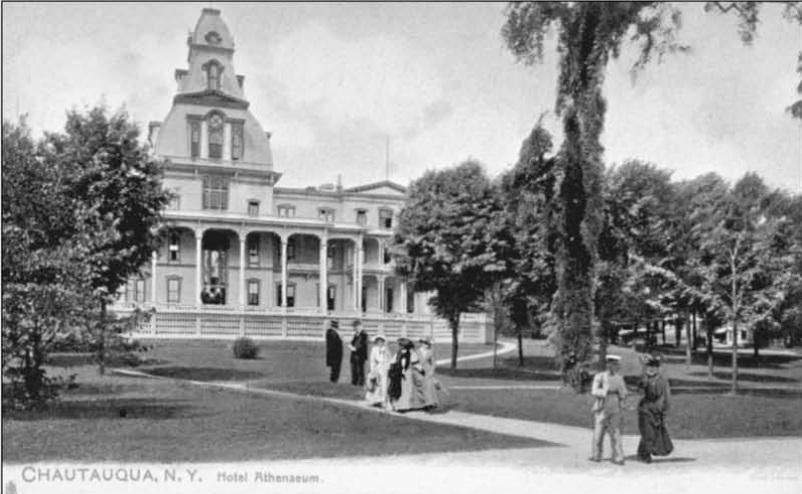

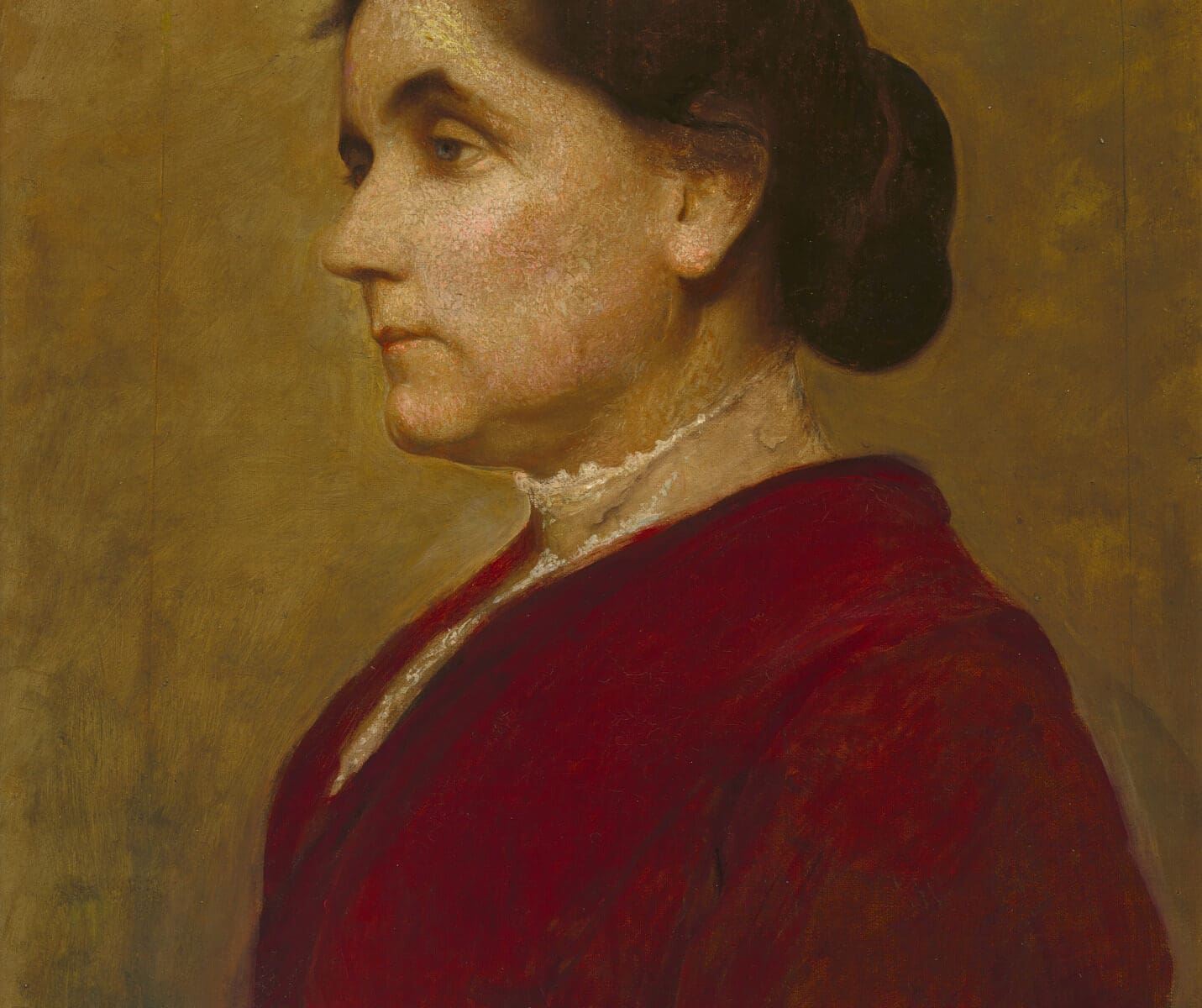

Jane Addams left Illinois for Chautauqua, New York, on Friday, July 4, 1902, at 3 p.m. Traveling on the New York Central Railroad, perhaps in a sleeping car, she had at least one book with her to read, as she always traveled with books. Onboard the train, Addams enjoyed the countryside passing by outside the train windows and engaged in casual conversation with fellow travelers. She may have snacked or had a light meal in the dining car and polished up her series of five lectures she was scheduled to deliver during her week-long stay at the Chautauqua Institution. She arrived in Chautauqua in the wee hours of the morning the following day and checked into the Athenaeum Hotel, a Second-Empire building opened to guests in 1881. The hotel boasted an ornate three-story tower with a mansard roof, centered on the front façade of the hotel. It stuck a magnificent pose from atop a small hill overlooking a deep lawn and Chautauqua Lake, matching in style the long skirts and elaborate hats of the women who strolled on the winding paths below it.

Exactly 123 years after Addams arrived in Chautauqua, I left Illinois for Chautauqua at 7:45 a.m. I drove by myself in my Ford Escape hybrid, stopping overnight in northern Indiana at my mom’s house. I drove the remaining six of the nine-hour journey the next day, snacking on cashews and dried mango while alternately listening to an audio book and rehearsing memorized sections of the one lecture that I was scheduled to deliver during my week-long stay at the Chautauqua Institution. I arrived in Chautauqua in the midafternoon on Sunday, July 6, and checked into the Athenaeum Hotel. Despite its peeling paint and the somewhat ragged appearance of the wicker chairs lined across the inviting two-story porches, the historical charm of the building calmed my road-weary spirit and my nerves, frazzled from sharing the road with semi-tractor trucks oblivious to speed limits. I would not learn it until later, but the stately hotel tower was two-stories shorter than the one that greeted Jane Addams in 1902, the upper stories having been dismantled for safety reasons in the 1920s. Still, in the hazy heat of July in 2025, the hotel was yesteryear grand, nestled as it was among mature trees and rich foliage, the Victorian porches already calling me. I made a vow to enjoy them each day of my visit, to drink coffee and watch every sunrise over the lake and sip cocktails as evening shadows fell over the enchanting, historic village.

Exactly 123 years after Addams arrived in Chautauqua, I left Illinois for Chautauqua at 7:45 a.m. I drove by myself in my Ford Escape hybrid, stopping overnight in northern Indiana at my mom’s house. I drove the remaining six of the nine-hour journey the next day, snacking on cashews and dried mango while alternately listening to an audio book and rehearsing memorized sections of the one lecture that I was scheduled to deliver during my week-long stay at the Chautauqua Institution. I arrived in Chautauqua in the midafternoon on Sunday, July 6, and checked into the Athenaeum Hotel. Despite its peeling paint and the somewhat ragged appearance of the wicker chairs lined across the inviting two-story porches, the historical charm of the building calmed my road-weary spirit and my nerves, frazzled from sharing the road with semi-tractor trucks oblivious to speed limits. I would not learn it until later, but the stately hotel tower was two-stories shorter than the one that greeted Jane Addams in 1902, the upper stories having been dismantled for safety reasons in the 1920s. Still, in the hazy heat of July in 2025, the hotel was yesteryear grand, nestled as it was among mature trees and rich foliage, the Victorian porches already calling me. I made a vow to enjoy them each day of my visit, to drink coffee and watch every sunrise over the lake and sip cocktails as evening shadows fell over the enchanting, historic village.

In 1902, Jane Addams was not only a featured lecturer for Chautauqua’s “Social Settlement Week,” but she also brought with her the Hull-House Summer School. After ten years at her alma mater in Rockford, Illinois, this year she was hosting the Summer School at Chautauqua Institution. Seventy young women, mostly teachers from Chicago, would reside in various cottages scattered across the Chautauqua campus, participate in a variety of Institution lectures on topics like pedagogy and history and participate in activities like swimming and an excursion to Niagara Falls. The students would also attend Addams’s lectures and then met with her each evening in a shelter by the ravine piazza of the Institution’s auditorium. Addams’s good friend and fellow settlement house leader Graham Taylor from Chicago Commons was also joining her as a member of the Chautauqua faculty that summer.

In 2025, I was at Chautauqua as part of a group assembled by President Lincoln’s Cottage, a historic site in Washington, DC, where Abraham Lincoln and his family lived for one-quarter of his presidency. It is the place where Lincoln wrote the Emancipation Proclamation and where he and his family grieved the death of eleven-year-old Willie Lincoln in 1862. Our group was leading a Master Class series to provide both historical and modern contexts for the Metropolitan Opera’s Chautauqua workshop of Lincoln in the Bardo, based on the novel of the same name about Willie’s death and his father’s grief. My lecture was part history about the Lincoln family and grief, and it also shared my personal story of grief and illustrated, as well, how my emotional connection to the figures I study informs my understanding of the past.

I was in Chautauqua because of my years as an editor of Abraham Lincoln’s papers, but I went to Chautauqua with Jane Addams in my head. I knew about the long, storied history of the Chautauqua Institution through my work editing Jane Addams’s papers, and I was eager to breathe in the place to which she returned many times during her long career as a reformer, writer, and renowned lecturer.

Chautauqua Institution was founded in 1874 by Episcopal Bishop John Heyl Vincent (1832-1920) and Lewis Miller (1829-1899), a religious leader, educator, and industrialist. The first Chautauqua assemblies were camp meetings for Sunday school teachers (attendees sleeping in actual tents!), but the organization expanded quickly four years later when Vincent established the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle (CLSC), a correspondence school which offered “courses of reading for all classes of people.” The early popularity of the CLSC and the growth of the Chautauqua Institution in western New York spurred the organization of Chautauqua societies across the country, the Chautauqua Movement promoting the idea of lifelong learning for adults, celebrating the most important work of educators, scientists, artists, writers, political leaders, and reformers, and espousing the idea that an educated public is a healthier public.

In his 1886 book The Chautauqua Movement, Vincent wrote: “Education, once the peculiar privilege of the few, must in our best earthy estate become the valued possession of the many. It is a natural and inalienable right of human souls.”

Jane Addams was a lifelong learner herself, and all of her reform work in Chicago and beyond was rooted in her steadfast belief that education and learning had power to lift up individuals and communities and help create a better world for all people. It is not surprising, then, that she supported the Chautauqua Movement, as did numerous leaders during the Progressive Era.

Addams’s trip to Chautauqua for Social Settlement Week in July 1902 was not her first. She previously lectured there in July 1893 as part of another program about social settlements, and she returned in July 1895. In August 1898, she lectured on “Aspects of the Social Problem,” and in August 1900, she was back to deliver four lectures. Jane Addams valued the mission of Chautauqua, speaking at numerous Chautauqua Movement events throughout the Midwest and returning to Chautauqua Institution as a featured lecturer six times between 1903 and 1915. Ill health forced her to turn down an invitation to Chautauqua in 1918, but as she wrote Arthur Bestor, president of Chautauqua Institution, in March of that year: “My plans are of necessity indefinite but as it is always a pleasure to me to speak at [Chautauqua] I shall hope to be able to arrange it this year.”

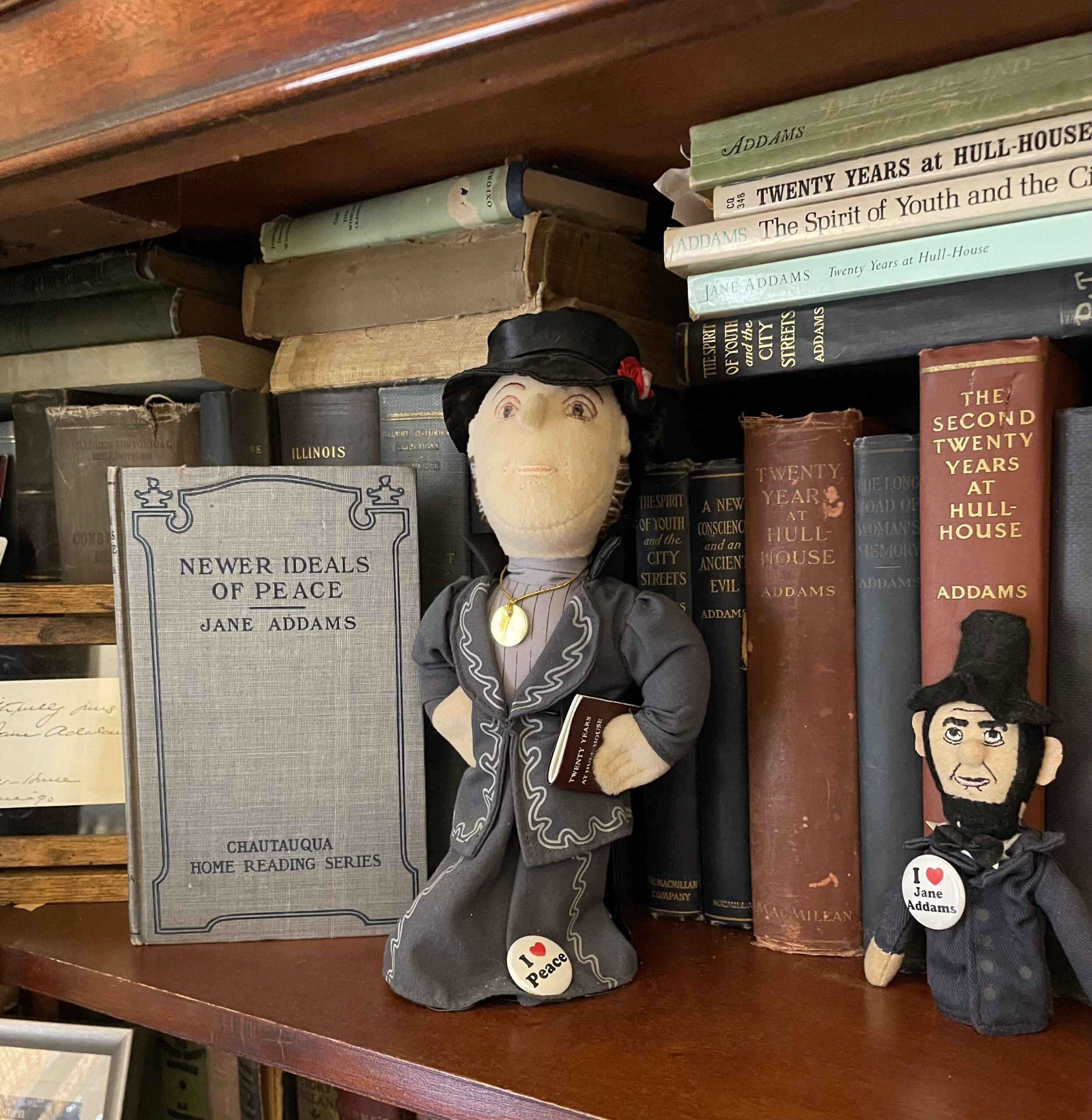

Two of Addams’s books were selected as part of the coveted CLSC’s annual reading curriculum: Newer Ideals of Peace in 1907-1908 and Twenty Years at Hull-House in 1911-1912. It is the Chautauqua Edition of Newer Ideals that I have in my Jane Addams cabinet of curiosities. The 2025 CLSC reading list includes one of my favorite books of recent years, Eve by scholar Cat Bohannon as well as Liberation Day, stories by George Saunders. Saunders was the featured lecturer at Chautauqua during the week I was there. He was present at the end of the week for the opera workshop of his brave and human novel Lincoln in the Bardo. Not bragging or anything, but it was a thrill for me to meet Saunders and have him inscribe my personal copy of Lincoln in the Bardo.

George Saunders was the star of my week at Chautauqua, but Jane Addams was always the star when she visited the Chautauqua Institution.

Even in 1915, when her peace work made her unpopular with some audiences, people clamored to read her books and articles, to meet her, and to hear her speak. In a speech at Chautauqua Institution in August that year, just four months after the United States entered the World War, she took the podium to defend herself. As an unwavering peace advocate, she was subject to criticism by many who believed that patriotism required total support of one’s government during wartime. Addams disagreed, believing instead that to be a patriot was to question the government and that free speech in time of war was even more important than in peacetime. In a speech at Carnegie Hall in New York on July 9, during which she had discussed her tour of Europe as part of the work of the International Congress of Women, Addams made some statements about soldiers, the use of stimulants in the European armies, and definitions of bravery that rankled many. However, at Chautauqua she reiterated those statements, reaffirmed the horror faced by men in the trenches, and celebrated the courage of soldiers.

I don’t know how the audience received her lecture, but that the Chautauqua Institution granted Jane Addams a forum to raise her voice of peace during a time of war, speaks to the Institution’s commitment to free speech and the free exchange of ideas.

I witnessed that commitment to free speech at Chautauqua, as well. In a crowded amphitheater on July 10, at the coveted daily 10:45 a.m. Chautauqua Institution lecture, I watched Deborah Rutter, the widely regarded and long-time director of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, defend her tenure leading the Center. Fired in February by President Trump for cultivating diversity and inclusion in the arts, Rutter spoke to the Chautauqua audience about the importance of creative expression in a democracy. She defended the Center’s mission to bring people of diverse backgrounds to perform on a variety of stages and to bring in audiences across all social, political, racial, ethnic, and economic divides. Her Chautauqua audience interrupted her speech numerous times in rousing applause of her arguments that art is important for art’s sake, that creative expression in dark political times can save us, and that we must support the arts even more strenuously now that some voices are under the threat of being silenced.

Jane Addams would have been every bit as impressed with the speech and the audience as I was.

My week at Chautauqua was inspiring, rewarding, eye-opening, and a little bit magical. It was a modern experience informed by my interest in and emotional connection to the past. I was there in the company of new friends and historical figures, Jane Addams front and center in my mind’s eye during my eight days on the Chautauqua campus. I am one of those history nerds who is always looking to run into ghosts of the past, and on that front my summer week in Chautauqua did not disappoint.

By Stacy Lynn, Associate Editor

Pro Reader Tip: Are you looking for suggestions for your next read? Consider consulting the CLSC Book List, 1878-2024. There is bound to be a perfect book for you to consider. Cheers and happy reading!

Sources: Jonathan David Schmitz and William Flanders, Postcard History Series, Chautauqua Institution (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2011), 13, 52; American National Biography; John H. Vincent, The Chautauqua Movement (Boston: Chautauqua Press, 1886), 2; “Next Season at Chautauqua,” The Buffalo (NY) Review, June 21, 1902, 5; “Chautauqua 1902,” The Chautauquan, 35 (July 1902): 385-411; “Railway Time Tables; Chicago Tribune, July 3, 1902, 15; “Personal Record,” The Daily Journal (Freeport, IL), July 3 1902, 4; “Jane Addams Goes East to Open Summer School,” Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1902, 4; “Chautauqua Is Open,” The Fredonia (NY) Censor, July 9, 1902, 5; “A Fair Chautauqua,” Buffalo (NY) Evening News, July 10, 1902, 1; “Chautauqua’s Success,” Buffalo Evening News, July 13, 1902, 24; “Jane Addams to Be at Chautauqua,” Buffalo Evening Times, Aug. 11, 1915, 5; Hull-House Bulletin, 1 (Dec. 1, 1896): 3; Hull-House Bulletin, 15 (Semi-Annual, 1902, no. 2): 4; Selected Papers of Jane Addams, vol. 3, 320, 437, 654n7; Democracy and Education, August 9, 1900; Jane Addams to Julia Clifford Lathrop, July 13, 1902; Chautauqua Girls to Jane Addams, c. August 1902; Jane Addams to Sarah Alice Addams Haldeman, August 15, 1903; Work and Play: Recognition Day Address, August 16, 1905; Hull-House Year Book 1906-1907; Macmillan Company to Jane Addams, October 11, 1906; Jane Addams to Sarah Alice Addams Haldeman, July 10, 1907; Newer Ideals in Education, July 3, 1908; George Platt Brett Sr. to Jane Addams, January 10, 1911; Peace, August 14, 1915; Jane Addams to Arthur Eugene Bestor, March 1, 1918, all in Jane Addams Digital Edition.

Cathy led off the panel talking about the “Big Picture: Conceiving a Digital Edition of Jane Addams’ Papers,” providing a short history of the Addams Papers microfilm and book projects, and the process that went into deciding to digitize the microfilm edition. The decisions to be made involved thinking through the audience for the edition and what kinds of tools and resources they needed. In addition, Cathy discussed the decision to use the Omeka database-driven platform for the digital edition rather than using text encoding using XML. Going with a web-publishing friendly system allowed the Addams Papers to design a site that not only provides deep metadata, but also manages the project’s internal workflow, tracking information on each document as it passes through our permissions and copyright checks, metadata and transcription, and proofreading. Cathy also talked about her desire to see the Addams Papers edition be flexible enough that scholars and students can use its materials to build their own research projects.

Cathy led off the panel talking about the “Big Picture: Conceiving a Digital Edition of Jane Addams’ Papers,” providing a short history of the Addams Papers microfilm and book projects, and the process that went into deciding to digitize the microfilm edition. The decisions to be made involved thinking through the audience for the edition and what kinds of tools and resources they needed. In addition, Cathy discussed the decision to use the Omeka database-driven platform for the digital edition rather than using text encoding using XML. Going with a web-publishing friendly system allowed the Addams Papers to design a site that not only provides deep metadata, but also manages the project’s internal workflow, tracking information on each document as it passes through our permissions and copyright checks, metadata and transcription, and proofreading. Cathy also talked about her desire to see the Addams Papers edition be flexible enough that scholars and students can use its materials to build their own research projects.