In June, Addams biographer and Project Advisory Board member Lucy Knight got in touch with a query regarding a claim that Hull-House was a segregated space until the 1930s. The claim first made by Thomas Lee Philpott in his 1978 work: The Slum and the Ghetto: Housing Reform and Neighborhood Work in Chicago, 1880-1930. It was repeated by Khalil Gibran Muhammed’s Condemnation of Blackness (2010), and then repeated by me in a 2015 blog post reporting on Khalil Muhammed’s talk at Ramapo College. Lucy wanted to know more, because the claim had begun appearing all over the web. Since then she has gathered evidence that refutes the statement.

I wrote that blog post a few weeks after launching the project at Ramapo and did not question the statement. I probably should have, but assumed that given the time and the place it was likely true. Today I want to give the question a little more light and attention.

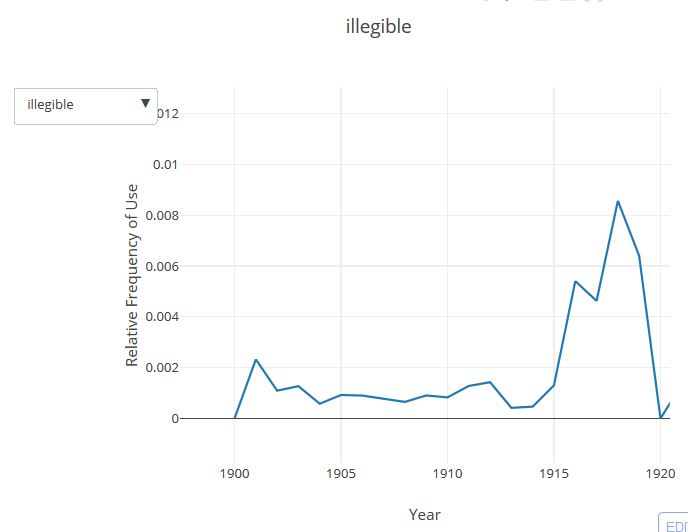

There is no smoking gun document — one in which a policy of segregation was clearly established. Without that it can be extremely difficult to prove whether or not African-Americans were welcome at Hull-House or in its programs and sponsored clubs. A majority of the records of Hull-House have not survived, which makes it unlikely that we will ever be able to definitively confirm or debunk the statement.

There are a couple of layers to the question. First, was Hull-House itself a segregated space? To that question, the answer is clear. It was not. Dr. Harriet Alleyne Rice (1866-1958), a Black physician and graduate of Wellesley College, started working at Hull House as early as 1893, working with the Hull-House branch of the Chicago Bureau of Charities and tending to the poor.

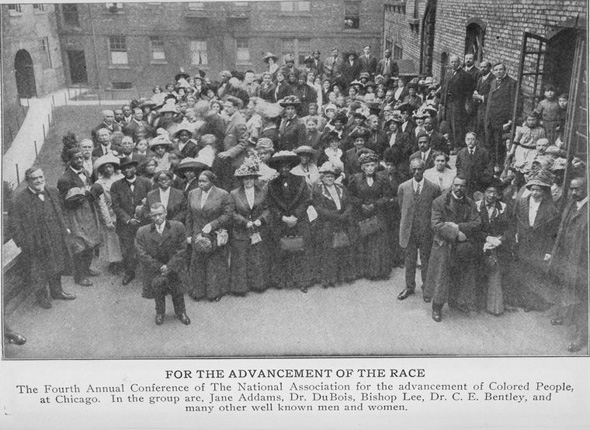

Addams invited Black speakers to Hull-House, including prominent figures such as W. E. B. Du Bois, who gave the speech “The Souls of Black Folk” at Hull-House on Lincoln’s birthday 1907 (Hull-House Year Book, 1906-1907). A year earlier, Atlanta newspaperman J. Max Barber spoke about the Atlanta race riot to a Hull House “audience mostly composed of negroes.” (Chicago Tribune, October 8, 190-6,. p. 3). Addams invited Ida B. Wells to visit and dine at Hull-House. And in 1912, Addams hosted a meeting of the interracial National Association for the Advancement of Colored People on the Hull-House grounds.

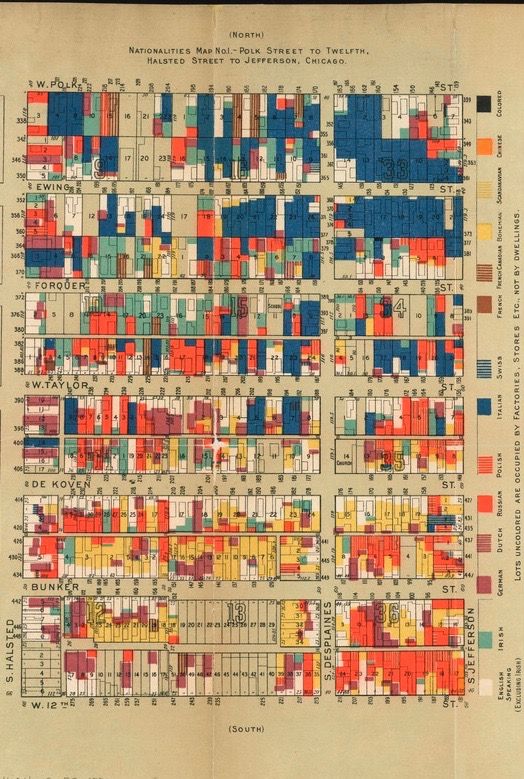

A more complicated question was whether Hull-House’s clubs and groups welcomed people of all races. Few if any spaces in Chicago were integrated during Jane Addams’s life. By 1910, the vast majority of African-Americans lived in Chicago’s South Side in what was known as the “Black Belt.” They formed their own organizations to empower their communities, much as other ethnic and religious groups did. African-Americans who came to Chicago during the Great Migration found opportunity, but also oppression.

Hull-House was located in the Near West Side, a overcrowded community that featured a wide range of European immigrants. The area was filled with ever changing languages and customs as Irish, German, Czech, and French immigrants were replaced by Jews from Russia and Poland, Italians and Greeks. In 1895, Hull-House workers surveyed the area showing the cultural (if not racial) diversity. It was not until the 1930s and 1940s that African-Americans and Mexican became a more significant presence in Hull-House’s neighborhood.

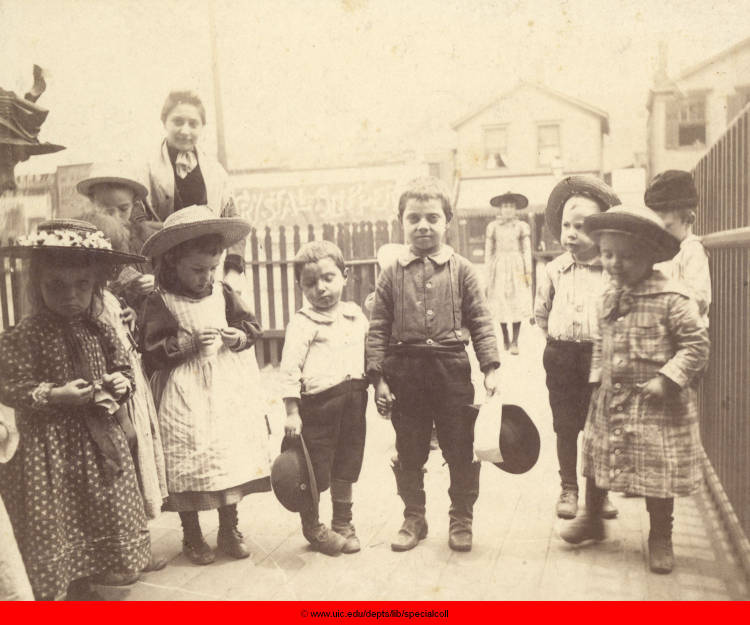

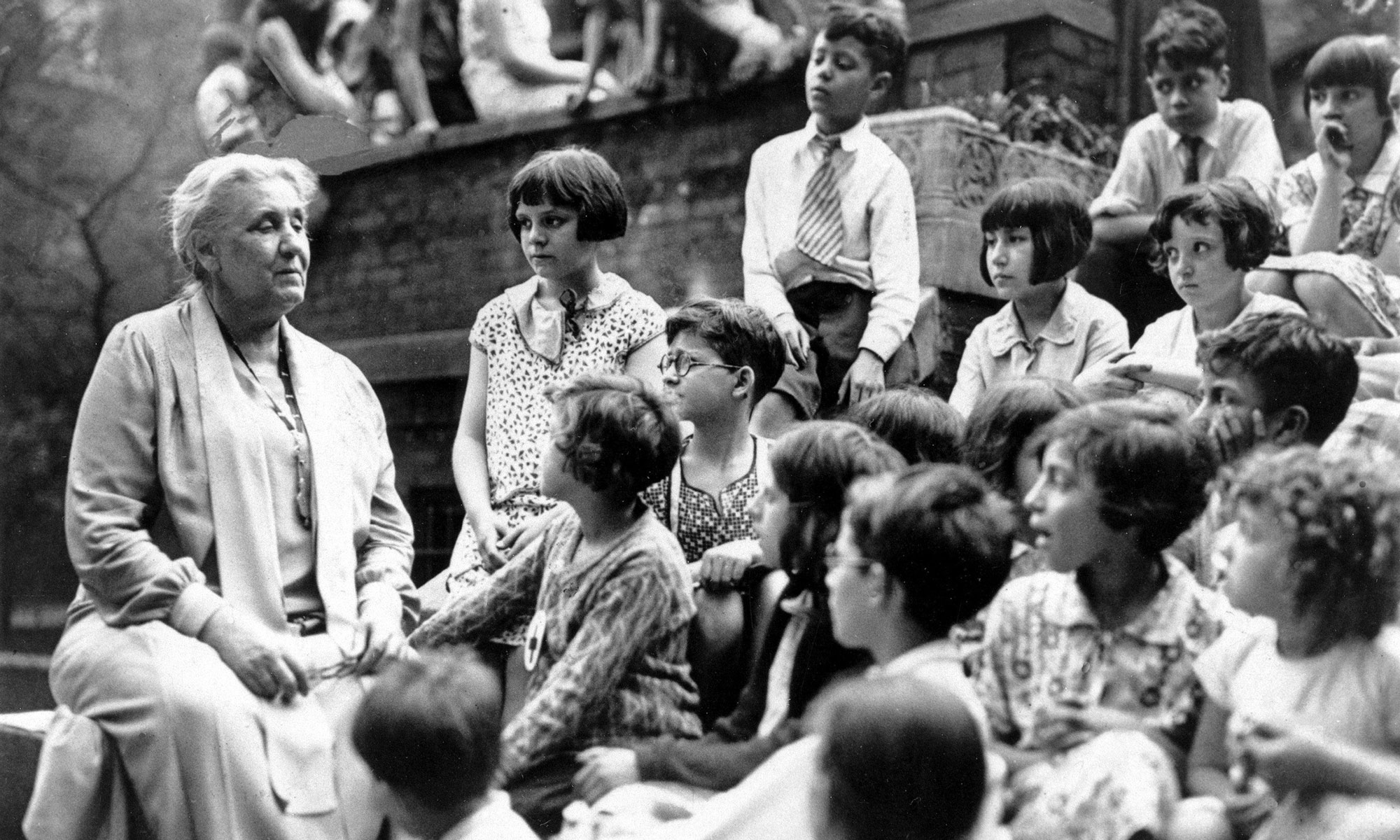

As a neighborhood-based settlement, Hull-House represented its surroundings, which meant that in its early years, the majority of its clientele were white immigrants. Photographs of early activities show this clearly.

Many of clubs and associations that operated out of Hull House were developed around ethnic affiliations, which was a way to retain community and customs in a time of rapid change and Americanization. The range of clubs at Hull-House was vast, and the numbers of people in and out of the Hull-House grounds reached nine thousand per week between 1906 and 1916. The clubs and associations were organized and operated by their members, some, like the “Greek Olympic Athletic Club,” were made up of Greek immigrants interested in athletics; others like the Hull-House Electrical Club, was made up of men who worked in electrical occupations. There were Greek and Russian social clubs, a 19th Ward Socialist Club, and the Jane Club, which was a co-operative boarding club for young women that operated its own house with thirty bedrooms. There were also general Men and Women’s Clubs, Boys and Girls’ Clubs, and educational programs in art, practical employment skills, and English language classes.

I find it unlikely that many of these clubs or programs were multi-racial in the first decades of Hull-House’s existence. Among the photographs of Hull-House activities located in archives at the University of Illinois at Chicago, photos from before 1920 depict what appear to be white groups.

There is some evidence of Black participation in clubs and groups at Hull-House before the 1930s. In 1913, the Chicago Defender wrote an obituary of George Williams, “the only Negro boy connected with Hull House as a member. He was a member of the band and took part in all the active branches of the settlement. Miss Jane Addams praised him to the highest. The day of his funeral the full band was out and his casket was borne by three Italians and one Jewish boy.” (Chicago Defender, September 20, 1913.)

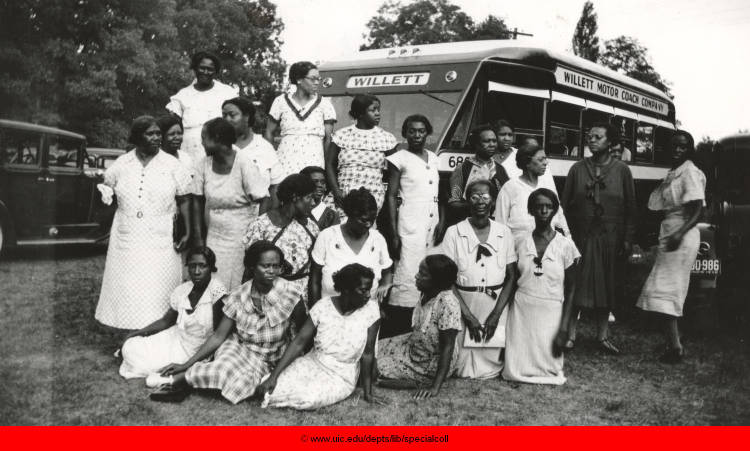

An African-American women’s club was formed at Hull-House in 1925, first called “The Colored Mothers’ Club,” and later the “Community Club.” They met on Monday evenings and held monthly interracial meetings which the Chicago Defender characterized as “not only harmonious and satisfactory, but very helpful.”

The Defender continued:

In and around Hull House a large number of the foreign population moved into other neighborhoods, and their places have been taken up by our group. The residents of the famous social settlement are still living up to their ideals of helping the people in the neighborhood to adjust themselves, and our boys and girls are urged to join all of the classes, and with their elders are cordially invited to take part in all the activities of the place. (Chicago Defender, December 11, 1926, p. 5.)

But, does this one newspaper article tell the whole story? By 1937, the Defender characterized the Community Club as the medium through which Hull-House worked among the African-American community. The club was affiliated with the National Federation of Colored Women and its focus was on bettering conditions for African-Americans in their community. (Chicago Defender, September 25, 1937, p. 19.) Did Hull-House push African-American activity off to the side into one or two clubs? Did African-Americans feel welcome in the late 1930s when they walked into the settlement?

Dewey Jones, the Assistant Director of Hull-House in 1938 reported during a 1939 speech that one long-time member of the Community Club had complained that its members were not invited to take part in general community events. In 1941 a caption on a photograph depicting Black women at the Jane Addams Memorial Lilac Ball on May 24, 1941 noted that “Director Charlotte Carr insisted that African Americans be invited to the Ball.” The fact that Carr’s action was noted, makes it appear that it was not the norm.

Florence Scala (1918-2007), an Italian-American resident of the West Side and a volunteer at Hull-House from 1934 to 1954, recalled that though the Near West Side had a great mix of ethnic groups, “there were no blacks, blacks were not active in the Hull-House programs when I was going there.” (Carolyn Eastwood, Near West Side Stories: Struggles for Community in Chicago’s Maxwell Street Neighborhood (2002), p. 139.)

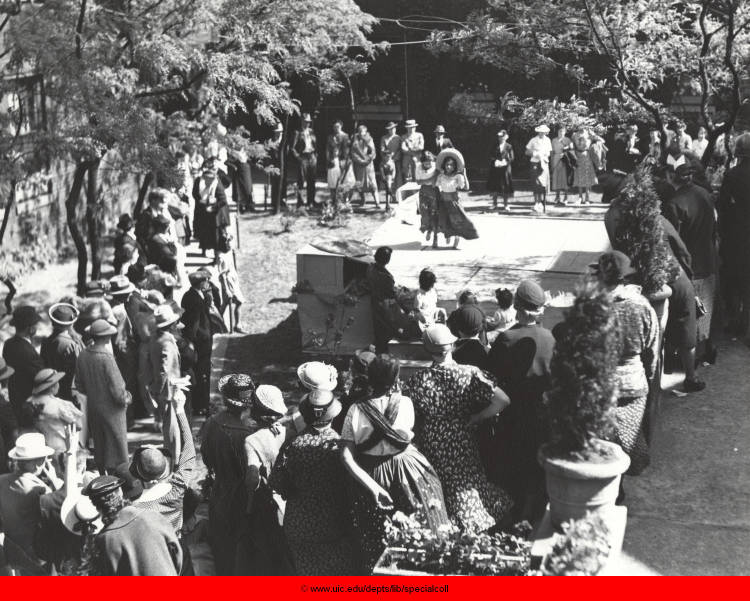

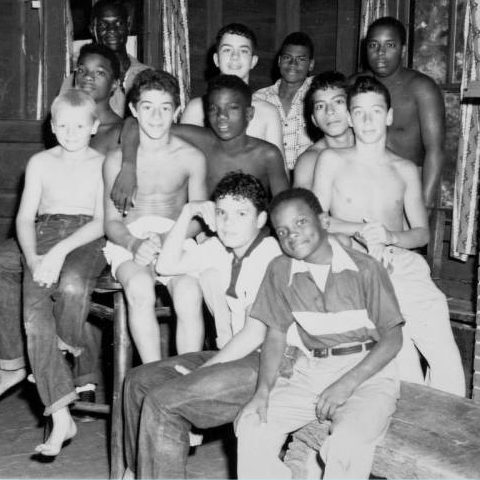

By the 1930s and especially by the early 1940s, photographs of Hull-House activities show the changing composition of the neighborhood. There were Mexican fiestas, and pottery classes, and photographs of integrated children’s activities at the Joseph T. Bowen Country Club.

So we are left with conflicting recollections and reporting. Did Florence Skala have a very different experience at Hull-House than the children who attended the Bowen camp in the 1940s? Were the adult activities more racially divided, broken into clubs that kept to their own kind? Without additional documentation, it is hard to make a determination that includes all the voices we have.

We can close with a look at what African-American reporters said at the death of Jane Addams in 1935. In an obituary written of Addams in 1935, Thyra Edwards of the Pittsburgh Courier focused on Addams and Hull-House with regard to race.

Jane Addams had no ‘attitude’ toward the Negro. To her he was just one of the citizenship, one part of the whole. She recognized that the distinction of color exposed him more easily to attack and discrimination at the same time, adding a moral responsibility upon Americans to work against extraordinary exploitation because of color.

When Negroes moved into Hull House, there was no ‘consultant’ as to whether they should be accepted and in what proportions. Quite simply, new neighbors had come to Hull House and they found their way into whatever classes or groups they chose. (Pittsburgh Courier, June 1, 1935, p. 9.)

Another tribute to Addams was published in the Chicago Defender, where Eugene Kinckle Jones remarked:

Jane Addams made no special effort to lead the Negro to the Promised Land but by no act or thought did she eliminate this race from the classes or groups most in need.’ At Hull House, they had no set place but they were eliminated from no place. In her condemnation of crime, she condemned lynching. In her belief in the extension of suffrage to all, she included the Negro in her ‘all.’ (Chicago Defender, June 29, 1935, p. 3.)

Thanks to Louise Knight for her research into the question which she graciously provided.

We are delighted to announce that, with a grant from the

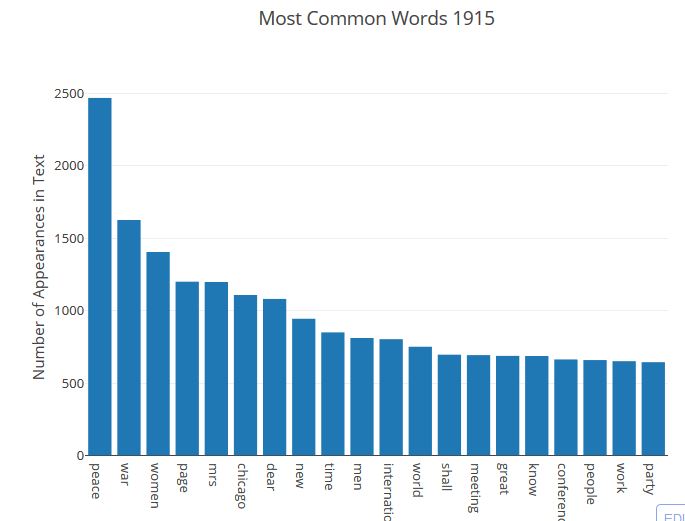

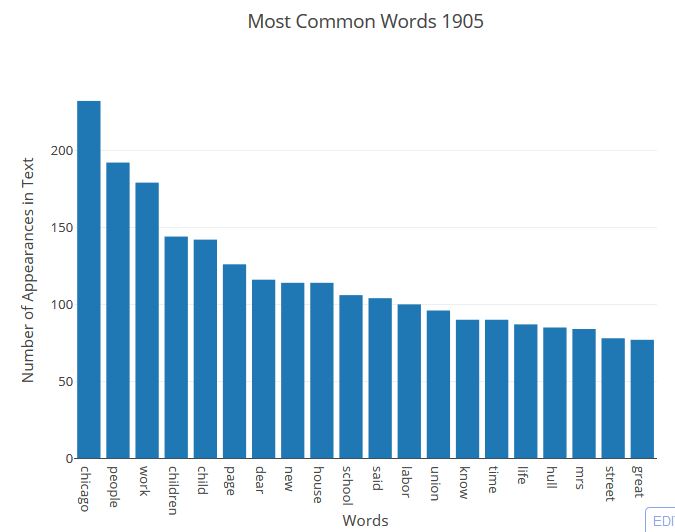

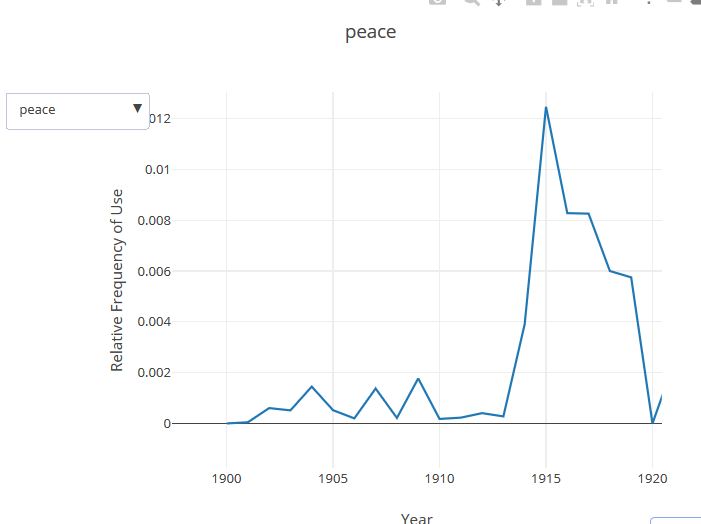

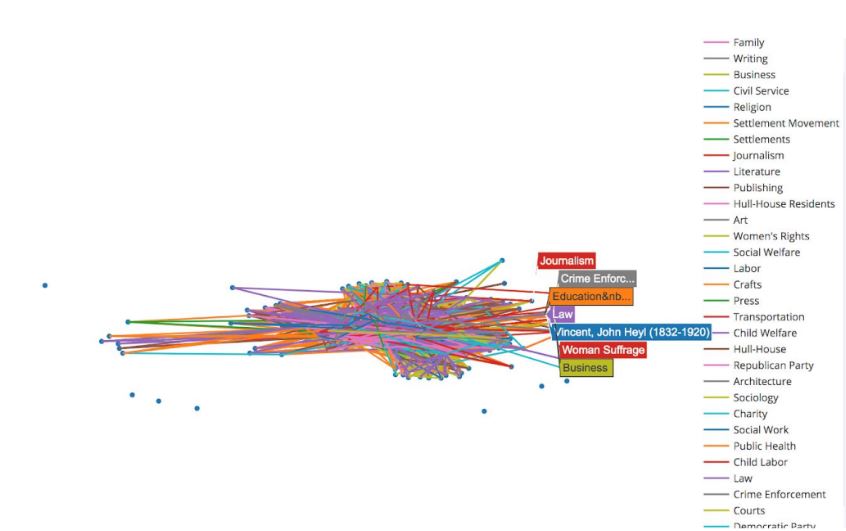

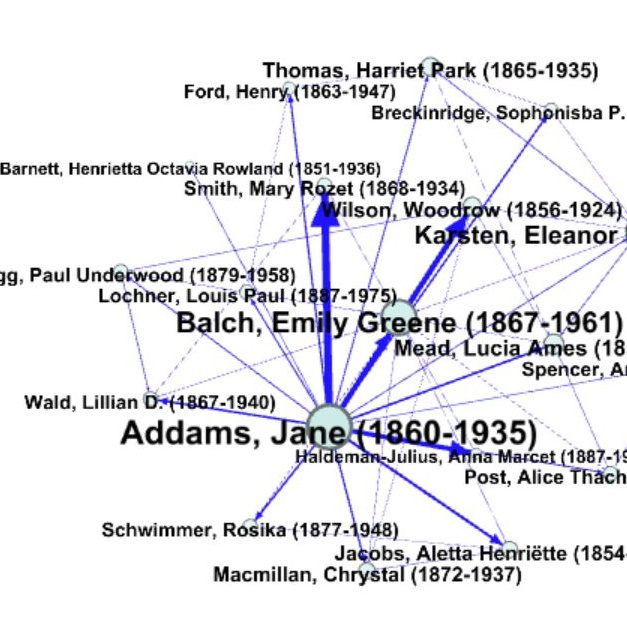

We are delighted to announce that, with a grant from the  Jane Addams’s work during the Progressive Era and early 20th century was wide-ranging, and available topics range from her work in establishing social settlements, professionalizing social work, fighting against child labor and the persecution of immigrants and African-Americans, working to win support for woman suffrage, and her efforts for peace and social justice through the Woman’s Peace Party and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Jane Addams’s work during the Progressive Era and early 20th century was wide-ranging, and available topics range from her work in establishing social settlements, professionalizing social work, fighting against child labor and the persecution of immigrants and African-Americans, working to win support for woman suffrage, and her efforts for peace and social justice through the Woman’s Peace Party and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

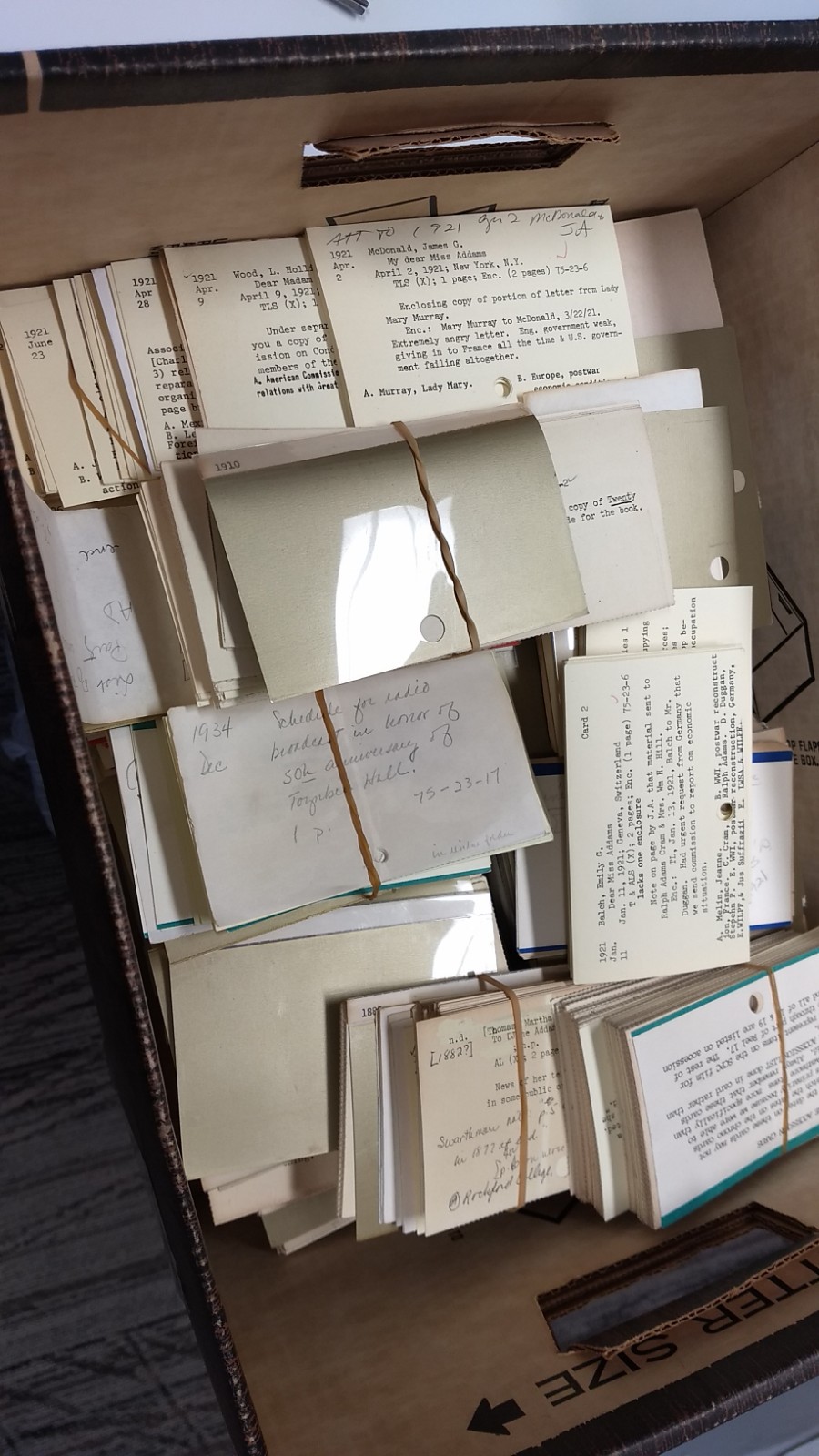

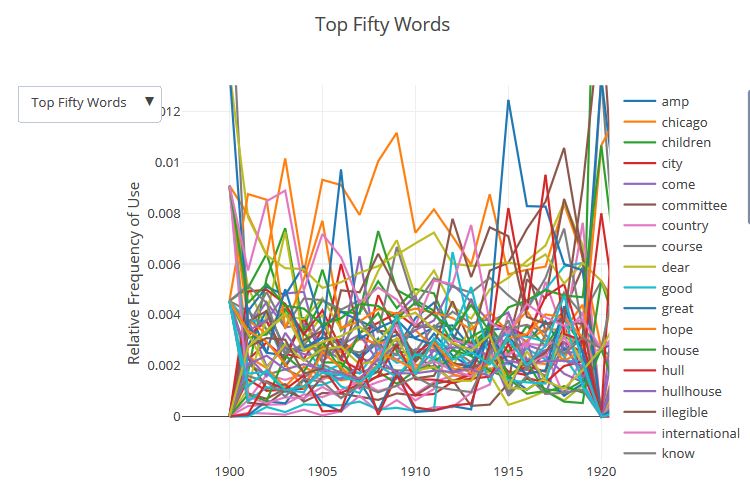

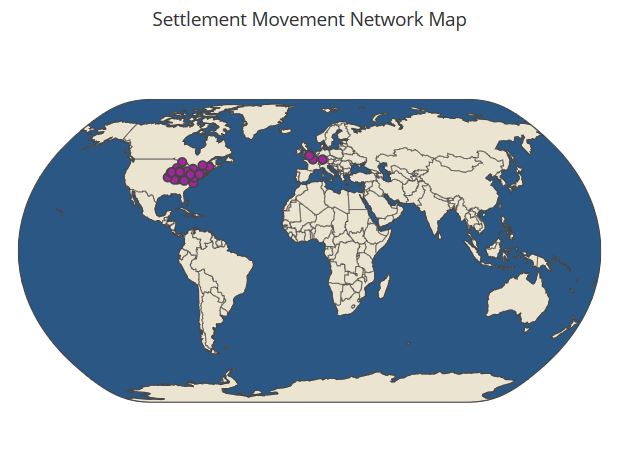

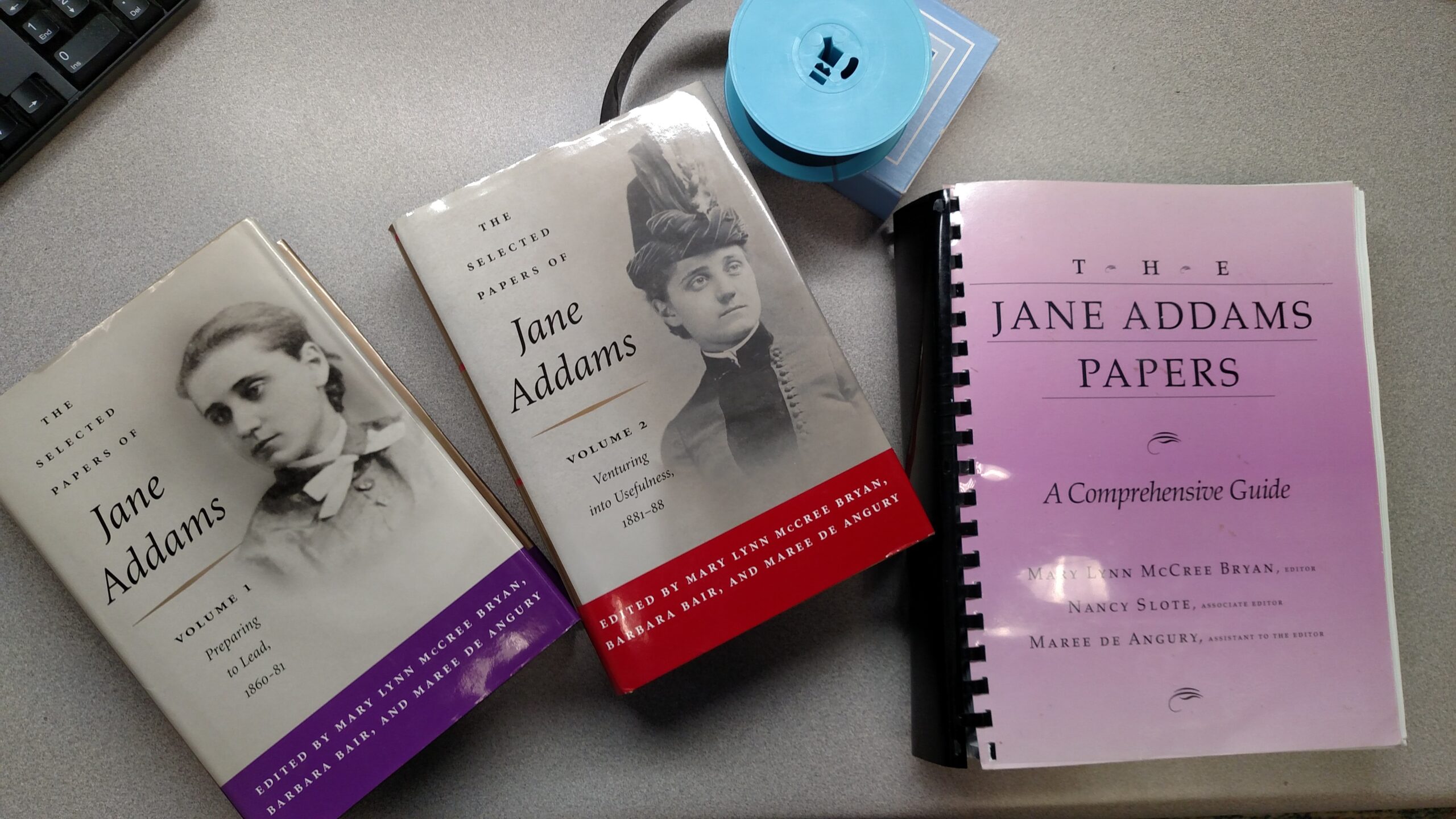

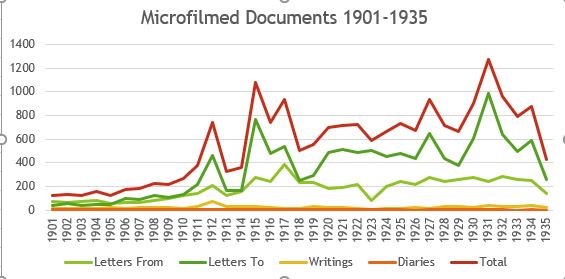

Working with a team of dedicated editors, Mary Lynn produced an amazing microfilm that became the basis for our digital edition. We scanned that microfilm in 2015 and started working with the images, beginning in 1901, on our digital edition. The microfilm edition represented decades of work; they conducted an international search for Addams documents in archives, private collections and published sources, organized the documents and indexed them. At the start of our project, they had published two volumes of the Selected Papers of Jane Addams (since then

Working with a team of dedicated editors, Mary Lynn produced an amazing microfilm that became the basis for our digital edition. We scanned that microfilm in 2015 and started working with the images, beginning in 1901, on our digital edition. The microfilm edition represented decades of work; they conducted an international search for Addams documents in archives, private collections and published sources, organized the documents and indexed them. At the start of our project, they had published two volumes of the Selected Papers of Jane Addams (since then